Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

Arms and Equipment: Cleaning the Firelock, part 2.

This installment of Arms and Equipment will be focused on surface treatments forIron, Steel and Brass.

Two Reproduction Bayonets likely made in the same factory overseas. Typically, many reproduction arms are mirror polished, inconsistent with known artifacts, and tools used by soldiers of the American Revolution. Cleaning arms correctly can be a very cheap way to begin “de-farbing” your firelock.

In 1786, Oxford Militia Serjeant Major Henry Trenchard published a pamphlet entitled “The Private Soldier and Militia Man’s Friend”. The Volume is an interesting look into the ordinary, day-to-day maintenance necessary for service in the militia or the regular Army. Just over 30 pages, Trenchard devotes half of the work to maintaining cleanliness of arms, accouterments and uniforms and contains valuable recipes and techniques used by the ordinary enlisted soldier:

“First you must provide yourself with a hand-vice, screwdrivers, rubbing sticks, and leather free from grease, oil, emery, crocus martis, &c. The rubbing sticks for the arms should be made of deal wood of different sizes,, with leather glued on in the following manner: Make the rubbing sticks very smooth, and on one side of it lay down the hot glue, and on this lay your leather and press it down; then lay some glue on the leather, and on that lay some emery, and press it a little into the glue, them be well dried; with this use oil and emery, brick dust &c; if you apply them properly by rubbing the arms well, they will give your arms a smooth surface you are next to proceed to polish them; take crocus martis, and clean dry leather, rub the part which you want to polish until it is warm, when it will acquire a very fine darkgloss”

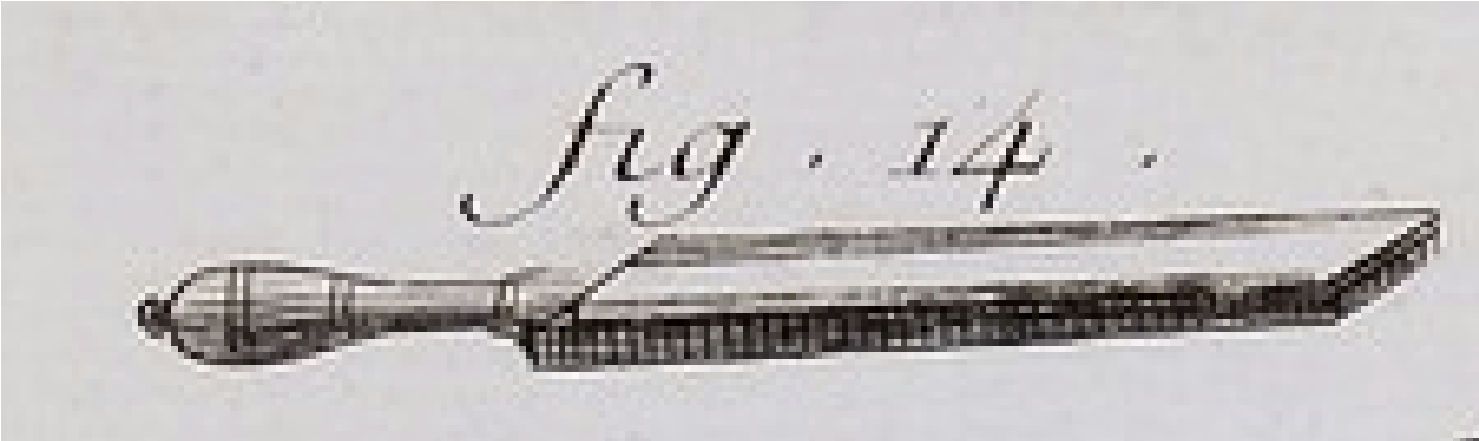

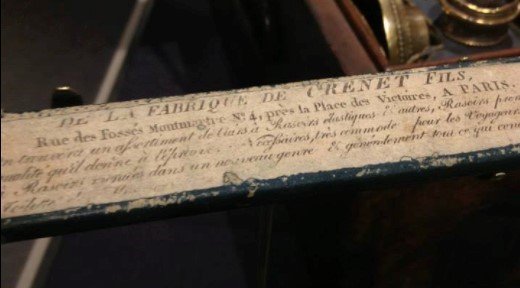

Trenchard’s above description of the rubbing sticks, serve as polishing strops, used in sharpening and polishing metal. A hint of what these may have looked like is from the Diderot’s Encylclopédie depicting tools from the cutler or Coutelier. One of those tools, described as a cuir à repasser, which was a “leather board” for polishing.

Another example of such a tool is in the French manufactured traveling case of Frederic Franck de la Roche, who served as an aide-de-camp to Marquis de Lafayette, in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society. From the original pasteboard case, it is clear that the strop was to be used with polishing razors for shaving.

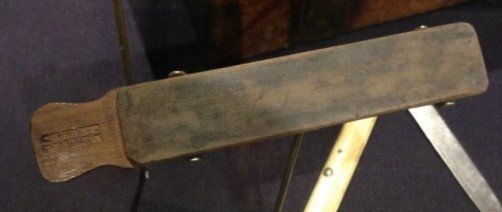

A few years ago I made this little strop, with a piece of scrap wood. Contact cement is a good adhesive if you’ve never used hide glue before. I used a piece of buff leather. I made it small to easily fit in any type of cartridge pouch, or pocket.

Such polishing boards/strops can be extremely useful in getting metal mirror bright. However, such a finish is unnecessary to strive for during ordinary cleaning “in the field.” All that is needed is oil, leather scraps, linen scraps or tow, and brick dust.

First, take two small pieces of brick and rub them together, collecting the dust in a small container. Take your Leather and/or strop and apply a little oil. Apply brick dust into leather by dipping or sprinkling; rub in a circular motion throughout the entire surface you wish to polish.

The Strop is very useful for flat surfaces, and areas of heavier rust. The leather scrap is very useful in curved and hard to reach areas. Experiment with your own techniques. For bigger polishing jobs a “paste” made from oil and brick dust can be very convenient. The more you polish the better it looks!

Sword before polishing:

Typical light rust from carrying in the field.

Sword after polishing:

Once complete, wipe down with a piece of tow, or scrap linen, cleaning out tight spots of brick dust.

Repeat as necessary. A final polishing option is to use rotten stone (a Google search revealed many places to purchase) in a similar manner on a separate clean piece of leather for a final polish, or as Serjeant Major Trenchard put it “a very fine gloss”.

After handling, a quick wipe-down with a lightly oiled rag will help keep rust fromdeveloping.

Thanks to Google Books, Trenchard’s book is available for free online:Google Books

ANDREW KIRKhas been involved with American Revolutionary War living history since the age of 13. Taking an interest in material culture of the British Army has led to creating reproductions of artifacts for TV, Film and Museum Projects. Trained as a fine artist and educator at Maryland Institute College of Art and has been a secondary art teacher in Maryland for 7 years.

British Army Muster Rolls: A Readers Guide

In our last installment of the 'Research Story' series, we opened the door to the great cavalcade of eighteenth-century British Army demographic information known as the muster roll (found in the WO12 series in the British National Archives). Of course, even more demographic information is contained in the general review returns (WO27), but that is a story for a different time. For now, I’ll focus on how one “reads” a British muster roll, because they aren’t necessarily straightforward to people who haven’t internalized British military procedure as I have. Or so my friends keep telling me.

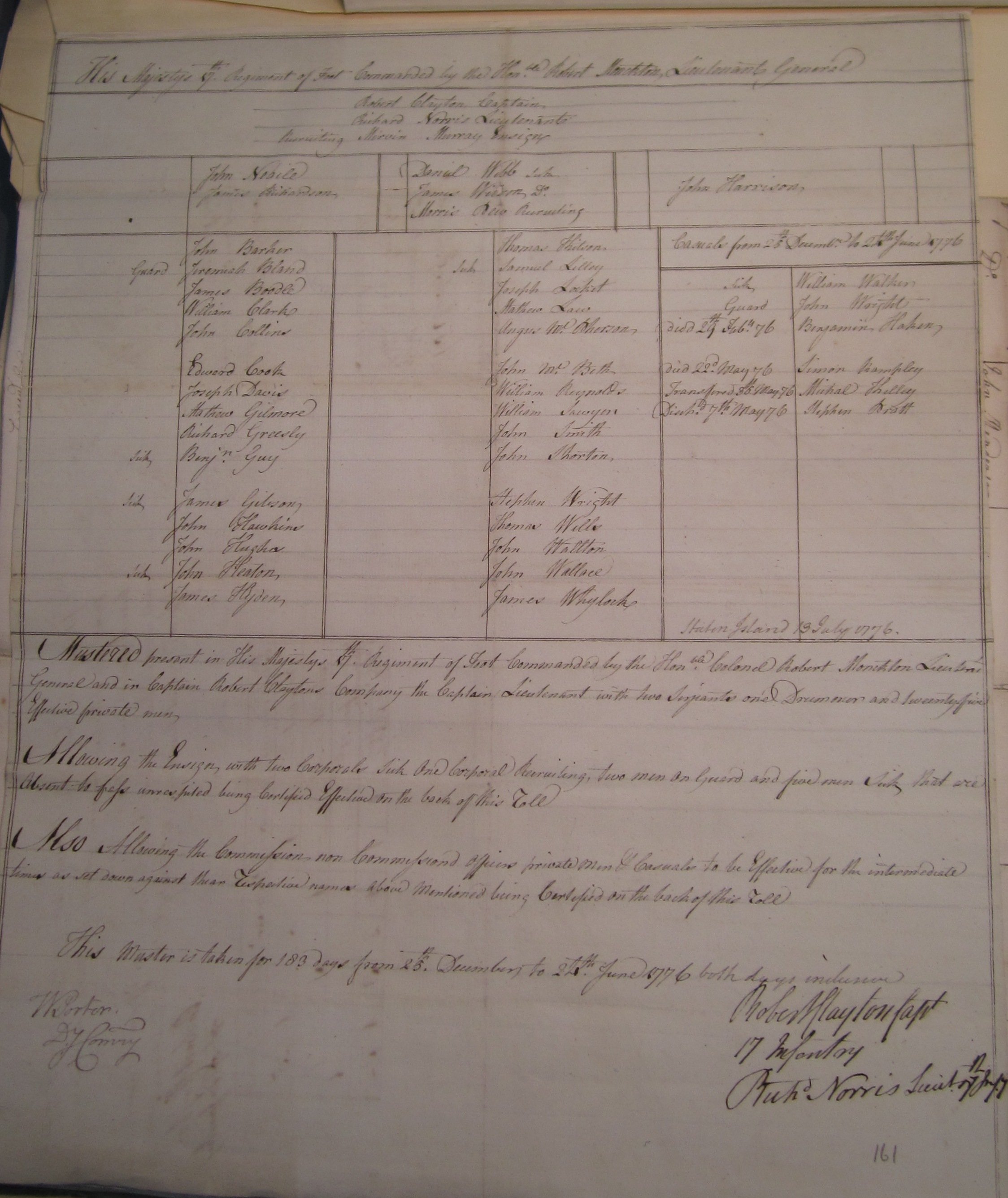

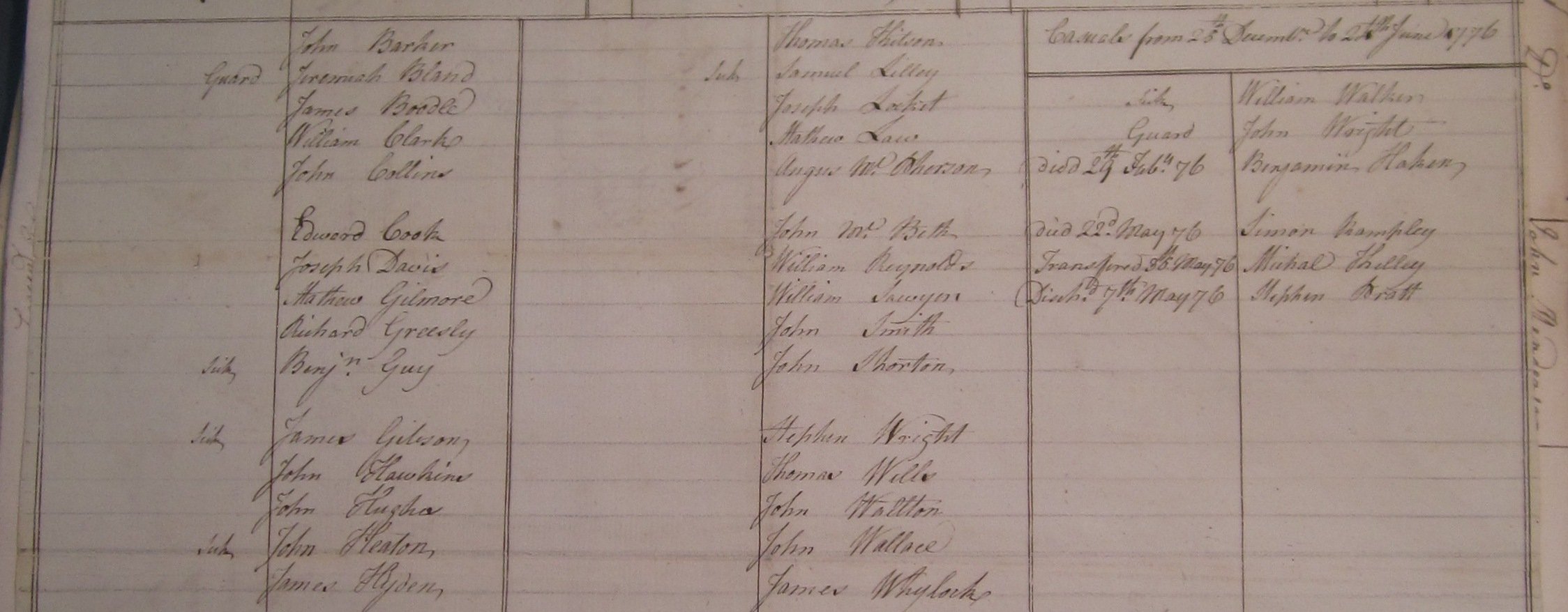

Here is a photograph (taken in 2011, pardon the quality) of the muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company of the 17th Regiment of Infantry, covering the period from December 1775-June 1776. As you can see, it is a multi-part document, following a standard format that you will find with any other regiment’s muster roll (with a tiny few exceptions). So even if you aren’t in love with the 17th, the following instruction is transferrable to other corps.

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

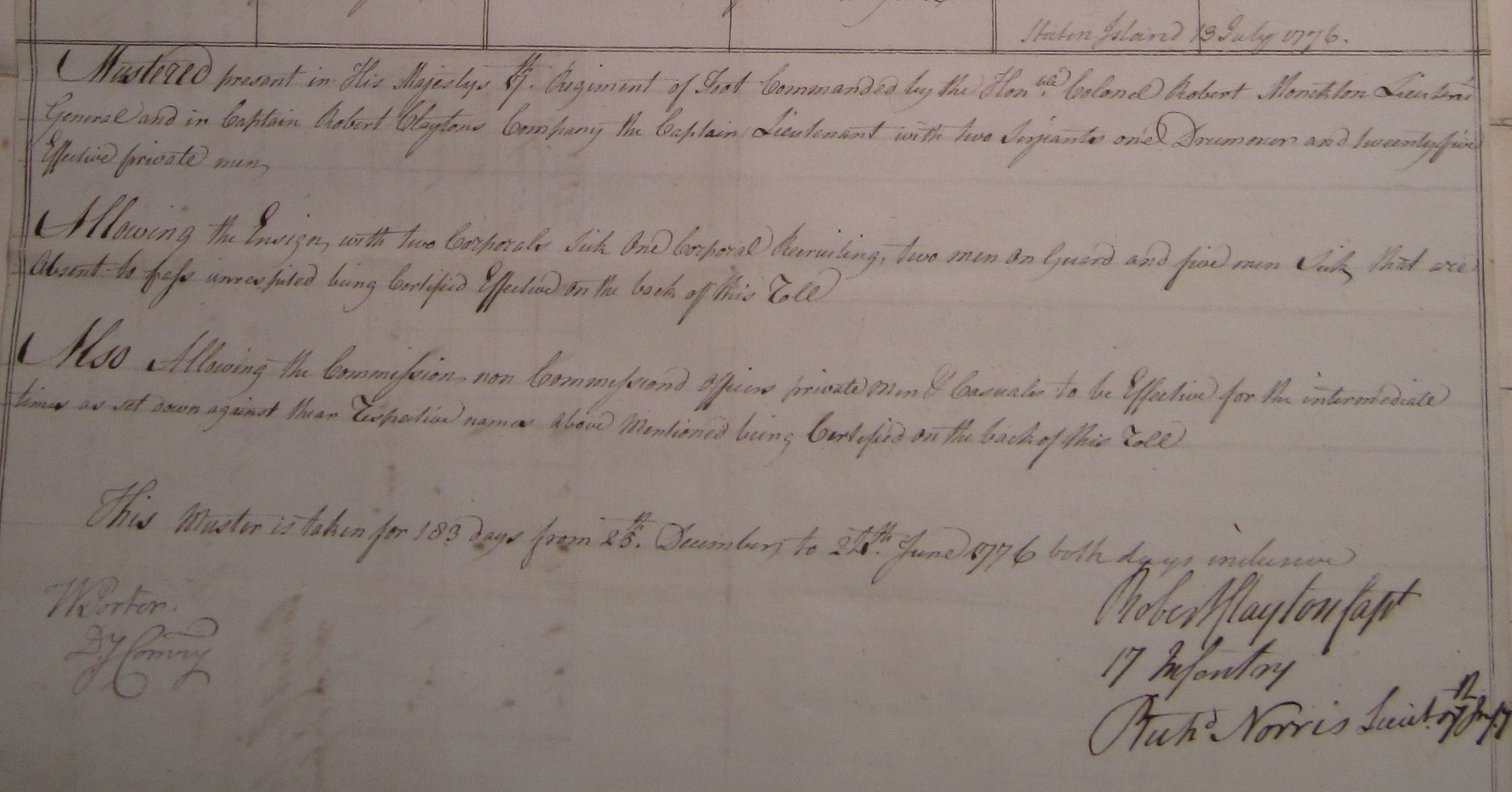

In this view of the document’s bottom half, we see several important pieces of information. First, there’s the location and date when the muster was taken—in this case, on Staten Island, July 13, 1776. Beneath that, you have a written synopsis of the information rendered above, which I’ll transcribe since the photo is blurry:

“Mustered present in His Majesty’s 17th Regiment of Foot Commanded by the Honble Colonel Robert Monckton Lieutenant General and in Captain Robert Claytons Company the Captain, Lieutenant with two Serjeants and Drummer and twenty five Effective private men.

Allowing the Ensign, with two Corporals Sick One Corporal recruiting, two men on Guard and five men Sick that are Absent to pass unrespited being Certified Effective on the back of this roll

Also allowing the Commission, non Commissiond Officers private Men & Casuals to be Effective for the intermediate times as set down against their Respective names above Mentioned being Certified on the back of this roll

This Muster is taken for 183 days from 25th December to 24th June 1776 both days inclusive”

This eighteenth-century military legalese is concerned with the prickly question of paying the army. Parliament passed an annual bill to fund the army, which was always subject to intense debate and scrutiny. From that point on, essentially every penny expending for military support had to be accounted for, since a scandal on misappropriation of funds or embezzlement could have dramatic negative effects on the army’s funding for the subsequent year. While plenty of period sources suggest that mustering was often accompany by significant bouts of corruption, with officer’s servants mustered to bring up the numbers of soldiers in a company to establishment strength, in general this process seems to have been taken fairly seriously by the Revolutionary War era. It is always important to note the date and location where the muster was taken and the dates the muster covers: in many regiments, several muster periods would be accounted for at one time, covering lengthy periods (sometimes extending to years) wherein the regiment could not be gathered and formally counted. A British regiment was expected to be mustered at six month intervals, so twice every year. Even if those musters couldn’t be made at the established intervals, the paperwork needed to be filled out at some juncture to satisfy officials in the Treasury Office.

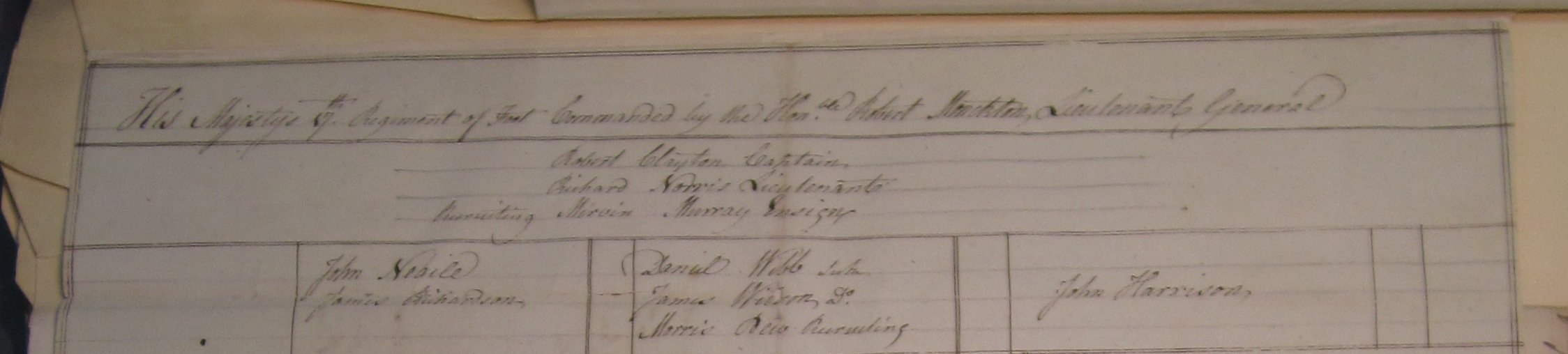

Heading back to the top, we see the first of the detailed name information contained in this return:

Beneath the unit identification and the colonel’s name, you see a list of the company’s officers: Captain Robert Clayton, Lieutenant Richard Norris, and Ensign Mervin Murray. Murray is listed on the recruiting service, meaning he is back in the British Isles with a serjeant and detachment of men attempting to drum up new recruit. Clayton and Norris were present with the company on the day of the muster--- when you see notes on the return that explain a man’s absence, that is only the excuse given for him being absent that day. So Clayton could have been on command at headquarters, far away from his company, the preceding day. That was one way officers could, theoretically, cheat the system: by being absent every day save for the muster and hiring local men to stand in for soldiers for the muster. Not as easy to pull off in America, however.

Below the officers, you have the list of non-commissioned officers. These are the serjeants, corporals, and drummers. In most returns, they will be labeled as such, though not here. Looking at the information from the bottom of the return, we would expect to see two serjeants, three corporals, and one drummer listed, and so they are. As in that synopsis, Serjeants John Neaile and James Richardson are present, along with Drummer John Harrison. Corporal Daniel Webb and Corporal James Wilson were ill on the day of the muster, while Corporal Morris Rew was off on the recruiting service, probably with Ensign Murray.

Now moving to the center portion of the return, we see two primary sections. The two columns to the left list all of the men who were expected to be with the company on muster day, including the excuses for those men who were not physically present. The right-hand section lists all of the causalities for the period of the muster: that includes men who left for any significant reason.

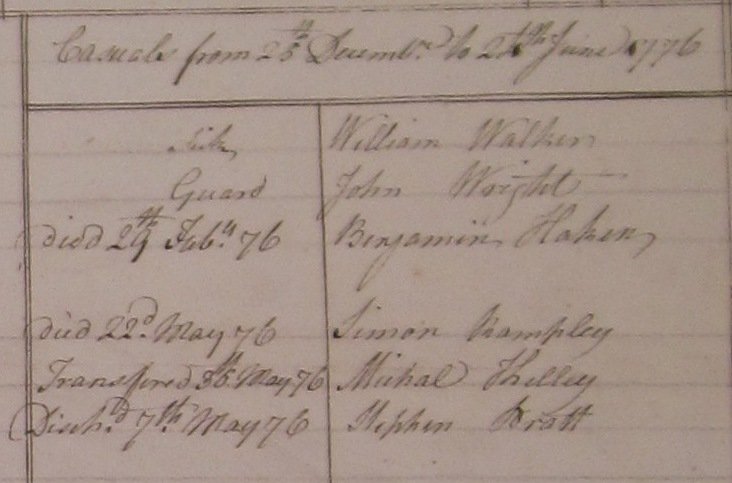

Focusing in on the casualty list, we see that it covers the same period as the rest of the muster and provides some interesting casualties beyond the men who died.

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Walker and Wright both stand out as outliers—plenty of the soldiers listed to the left were either sick or on guard. Perhaps the muster master forgot to list them and thus stuck them under the Casualties? Maybe Walker was seriously ill and Wright had been sent to a long-term guard detachment? The return doesn’t indicate answers, hence we call these leads for further research.

Beneath Walker and Wright, one sees the standard list of men who died. It was highly unusual for a six month period to pass without deaths in the regiment. You’ll see both the soldiers killed in battle as well as those who succumbed to disease, wounds, or accidents listed in this area, usually without any further explanation other than their official date of death. We also have Private Kelley, who transferred out of this company, probably into another company of the 17th. Often, when a regiment is drafted, you’ll see notations made adjacent to soldiers’ names about when they left and which corps they joined. Similarly, when men are drafted into a regiment, you’ll see that noted, usually with the comment “Enter’d” followed by the date. The same style is used for new recruits, so sometimes things can be a bit confusing when you know that men are being drafted and recruited in, but the muster master didn’t make a note. That’s why we use a range of sources together to correct for the weaknesses in individual sources. This particular sheet is fairly routine, only have a mix of sick and guard duty listed.

So there you have your basic guide to reading a British regimental muster roll sheet: while they can be tiresome one at a time, taken collectively they open up grand new vistas on the busy internal life of the British Army. We are reliably informed that Don Hagist is working on a massive muster roll project, recording all of the surviving data on British regiments that served in America into an interactive digital spreadsheet. Can’t wait to see those results! For more 17th Regiment-specific data, keep your eyes out for future posts here.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Over the subsequent years, he has traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain researching the eighteenth-century British Army and used the results of those labor to improve living history interpretations. The beginning of this journey in 2001 marked the start of the current recreated 17th Infantry.