Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

British Army Muster Rolls: A Readers Guide

In our last installment of the 'Research Story' series, we opened the door to the great cavalcade of eighteenth-century British Army demographic information known as the muster roll (found in the WO12 series in the British National Archives). Of course, even more demographic information is contained in the general review returns (WO27), but that is a story for a different time. For now, I’ll focus on how one “reads” a British muster roll, because they aren’t necessarily straightforward to people who haven’t internalized British military procedure as I have. Or so my friends keep telling me.

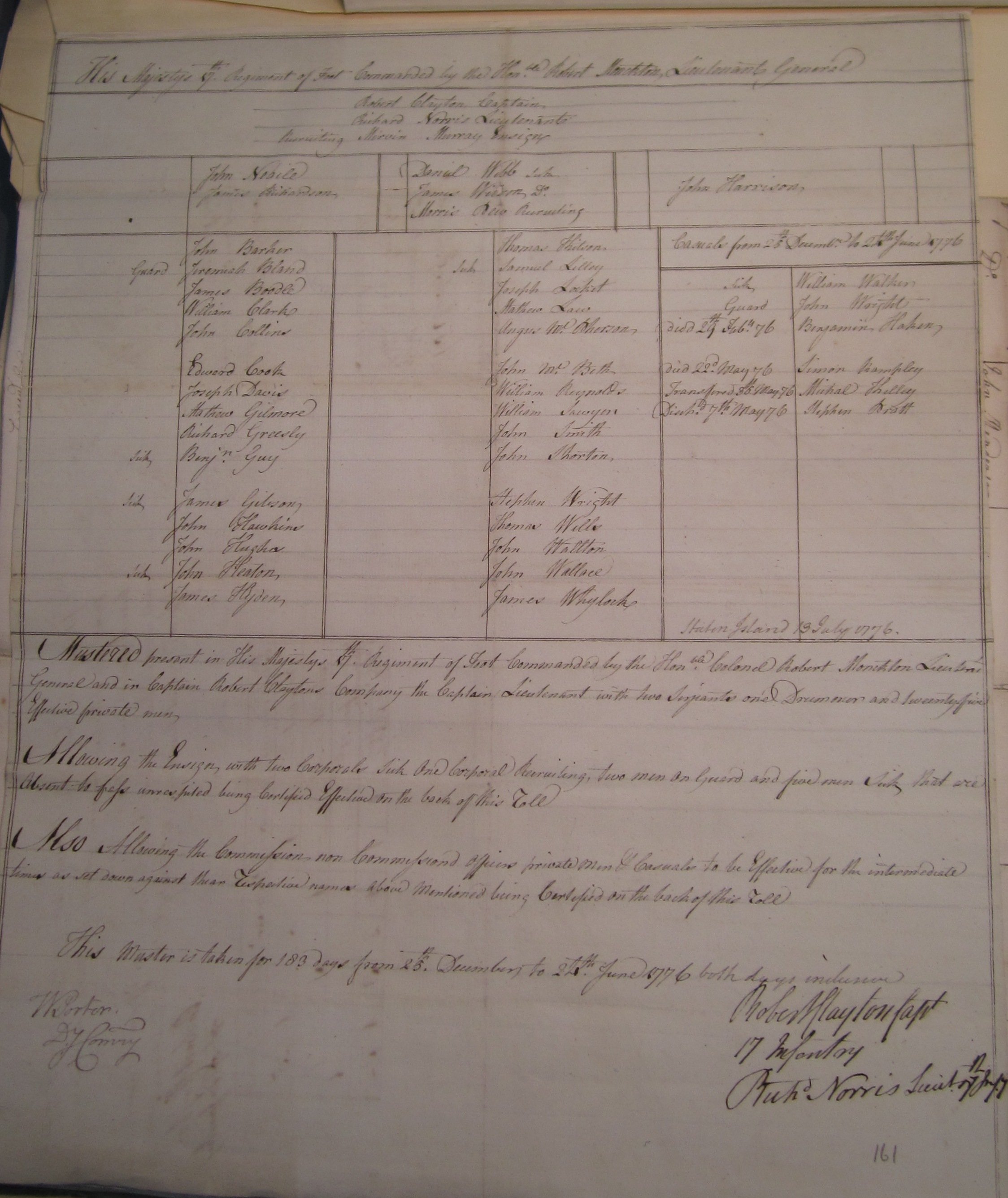

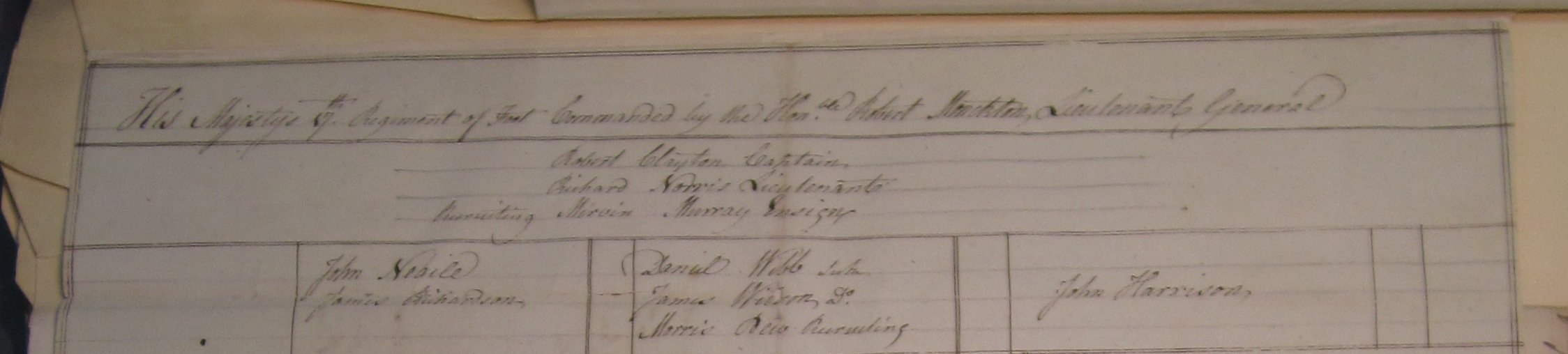

Here is a photograph (taken in 2011, pardon the quality) of the muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company of the 17th Regiment of Infantry, covering the period from December 1775-June 1776. As you can see, it is a multi-part document, following a standard format that you will find with any other regiment’s muster roll (with a tiny few exceptions). So even if you aren’t in love with the 17th, the following instruction is transferrable to other corps.

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

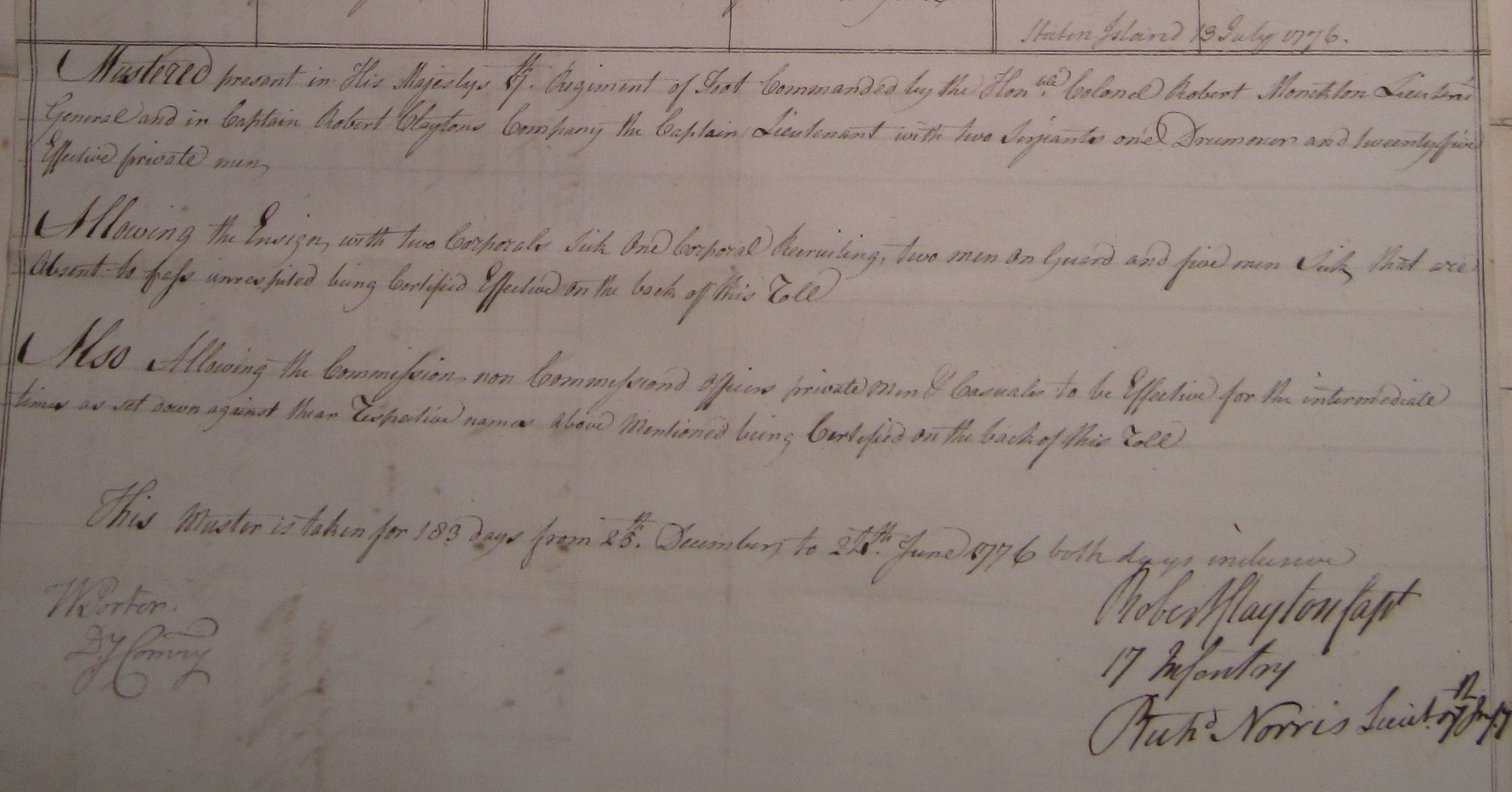

In this view of the document’s bottom half, we see several important pieces of information. First, there’s the location and date when the muster was taken—in this case, on Staten Island, July 13, 1776. Beneath that, you have a written synopsis of the information rendered above, which I’ll transcribe since the photo is blurry:

“Mustered present in His Majesty’s 17th Regiment of Foot Commanded by the Honble Colonel Robert Monckton Lieutenant General and in Captain Robert Claytons Company the Captain, Lieutenant with two Serjeants and Drummer and twenty five Effective private men.

Allowing the Ensign, with two Corporals Sick One Corporal recruiting, two men on Guard and five men Sick that are Absent to pass unrespited being Certified Effective on the back of this roll

Also allowing the Commission, non Commissiond Officers private Men & Casuals to be Effective for the intermediate times as set down against their Respective names above Mentioned being Certified on the back of this roll

This Muster is taken for 183 days from 25th December to 24th June 1776 both days inclusive”

This eighteenth-century military legalese is concerned with the prickly question of paying the army. Parliament passed an annual bill to fund the army, which was always subject to intense debate and scrutiny. From that point on, essentially every penny expending for military support had to be accounted for, since a scandal on misappropriation of funds or embezzlement could have dramatic negative effects on the army’s funding for the subsequent year. While plenty of period sources suggest that mustering was often accompany by significant bouts of corruption, with officer’s servants mustered to bring up the numbers of soldiers in a company to establishment strength, in general this process seems to have been taken fairly seriously by the Revolutionary War era. It is always important to note the date and location where the muster was taken and the dates the muster covers: in many regiments, several muster periods would be accounted for at one time, covering lengthy periods (sometimes extending to years) wherein the regiment could not be gathered and formally counted. A British regiment was expected to be mustered at six month intervals, so twice every year. Even if those musters couldn’t be made at the established intervals, the paperwork needed to be filled out at some juncture to satisfy officials in the Treasury Office.

Heading back to the top, we see the first of the detailed name information contained in this return:

Beneath the unit identification and the colonel’s name, you see a list of the company’s officers: Captain Robert Clayton, Lieutenant Richard Norris, and Ensign Mervin Murray. Murray is listed on the recruiting service, meaning he is back in the British Isles with a serjeant and detachment of men attempting to drum up new recruit. Clayton and Norris were present with the company on the day of the muster--- when you see notes on the return that explain a man’s absence, that is only the excuse given for him being absent that day. So Clayton could have been on command at headquarters, far away from his company, the preceding day. That was one way officers could, theoretically, cheat the system: by being absent every day save for the muster and hiring local men to stand in for soldiers for the muster. Not as easy to pull off in America, however.

Below the officers, you have the list of non-commissioned officers. These are the serjeants, corporals, and drummers. In most returns, they will be labeled as such, though not here. Looking at the information from the bottom of the return, we would expect to see two serjeants, three corporals, and one drummer listed, and so they are. As in that synopsis, Serjeants John Neaile and James Richardson are present, along with Drummer John Harrison. Corporal Daniel Webb and Corporal James Wilson were ill on the day of the muster, while Corporal Morris Rew was off on the recruiting service, probably with Ensign Murray.

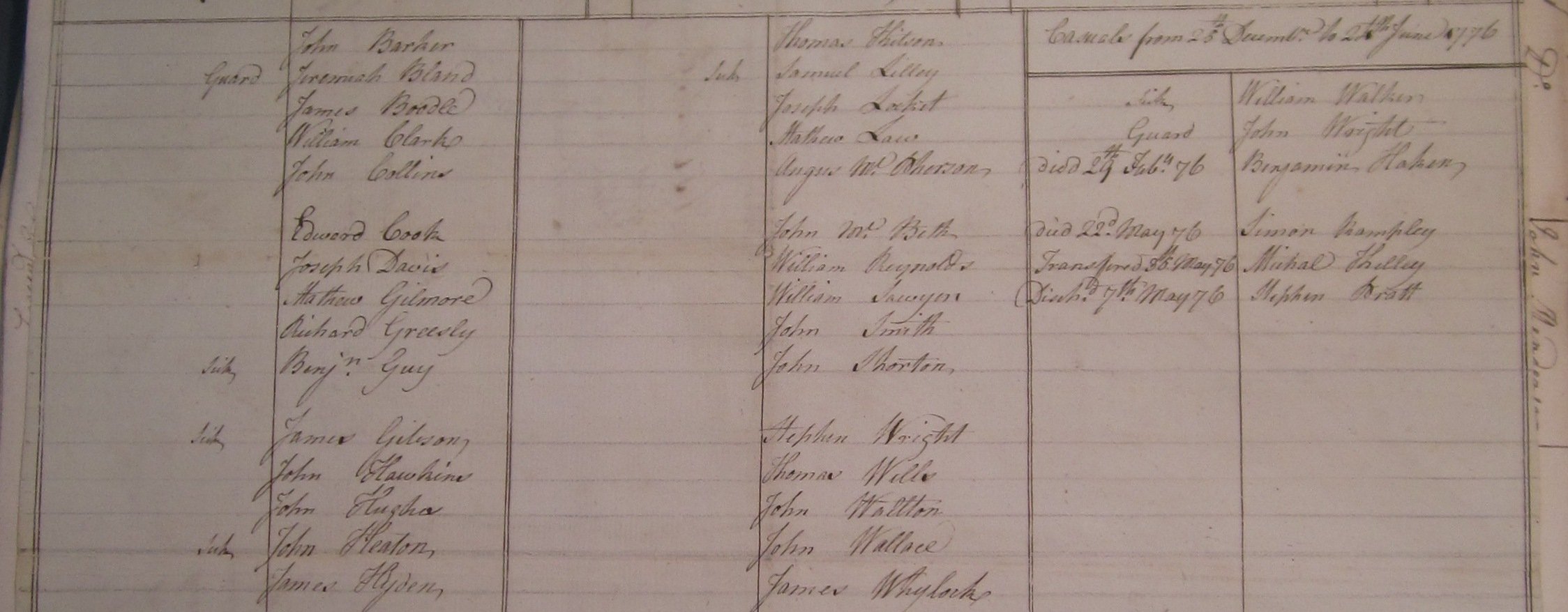

Now moving to the center portion of the return, we see two primary sections. The two columns to the left list all of the men who were expected to be with the company on muster day, including the excuses for those men who were not physically present. The right-hand section lists all of the causalities for the period of the muster: that includes men who left for any significant reason.

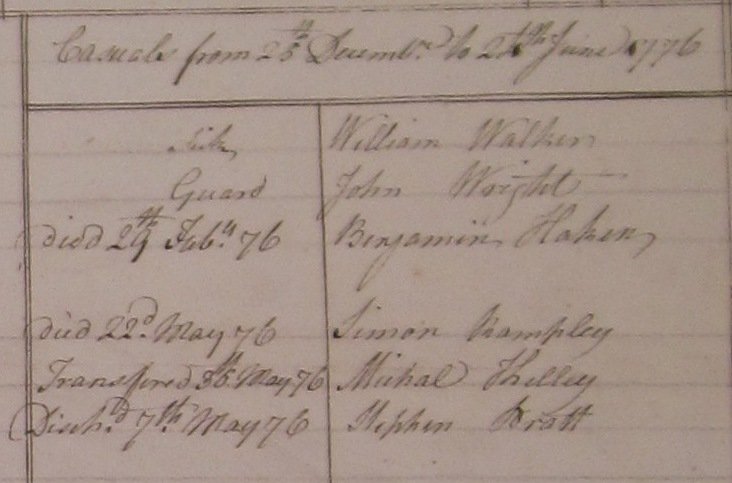

Focusing in on the casualty list, we see that it covers the same period as the rest of the muster and provides some interesting casualties beyond the men who died.

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Walker and Wright both stand out as outliers—plenty of the soldiers listed to the left were either sick or on guard. Perhaps the muster master forgot to list them and thus stuck them under the Casualties? Maybe Walker was seriously ill and Wright had been sent to a long-term guard detachment? The return doesn’t indicate answers, hence we call these leads for further research.

Beneath Walker and Wright, one sees the standard list of men who died. It was highly unusual for a six month period to pass without deaths in the regiment. You’ll see both the soldiers killed in battle as well as those who succumbed to disease, wounds, or accidents listed in this area, usually without any further explanation other than their official date of death. We also have Private Kelley, who transferred out of this company, probably into another company of the 17th. Often, when a regiment is drafted, you’ll see notations made adjacent to soldiers’ names about when they left and which corps they joined. Similarly, when men are drafted into a regiment, you’ll see that noted, usually with the comment “Enter’d” followed by the date. The same style is used for new recruits, so sometimes things can be a bit confusing when you know that men are being drafted and recruited in, but the muster master didn’t make a note. That’s why we use a range of sources together to correct for the weaknesses in individual sources. This particular sheet is fairly routine, only have a mix of sick and guard duty listed.

So there you have your basic guide to reading a British regimental muster roll sheet: while they can be tiresome one at a time, taken collectively they open up grand new vistas on the busy internal life of the British Army. We are reliably informed that Don Hagist is working on a massive muster roll project, recording all of the surviving data on British regiments that served in America into an interactive digital spreadsheet. Can’t wait to see those results! For more 17th Regiment-specific data, keep your eyes out for future posts here.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Over the subsequent years, he has traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain researching the eighteenth-century British Army and used the results of those labor to improve living history interpretations. The beginning of this journey in 2001 marked the start of the current recreated 17th Infantry.

A Layman’s Guide to Historic Research

This week after a few weeks of rather heavy research and unit development blogs, writer Kyle Timmons joins us again to welcome back the website with a light hearted research blog. If you've missed the blog, it is back! Thanks for standing by us.

Mary Sherlock - An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry.

Just a disclaimer to start off with: I AM NOT A HISTORIAN, HISTORY TEACHER, RESEARCHER, ARCHAEOLOGIST, OR ANYTHING LIKE IT. I am a simple person who enjoys history immensely and I’ve read and studied history much of my life. HOWEVER, I have the honor and privilege of being friend and acquaintance to many truly gifted and highly regarded Professional Historians. They’ve taught me so much about the 18th Century, the Revolution, and the British Army. But most importantly, they’ve given me the tools research on my own and to hunt down information that is of interest to me, and hopefully I can turn that information around and further benefit the hobby, the community, and our understanding of the 18th century. I’m going to take some time and share some of those tools with you.

- BE SUSPICIOUS. The moment that you read that previous statement is gone, and is never coming back. You can’t change it. But in an hour when you’re eating delicious food and playing on your phone you’ll likely forget about it. Maybe tomorrow you’ll share your memory of this blog with a friend, but you’ll share the points in your own words. You might get things wrong. 60 years from now when you’re telling your grandchildren how you first got into reenacting you’re memory of the antiquated computer or smart phone you used back then will be colored by nostalgia of the past.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

- YOU MAY BE WRONG BUT YOU MAY BE RIGHT. The modern age we live in is actually an exciting time for someone with a history interest. That’s because high definition imagery and the internet are making it easy for someone in the United States to view an artifact or painting housed in England, or Germany, or anywhere else in the world in detail from the comfort of their home. Books, journals, etc. that are no longer in print or are one of a kind have likewise been digitized and can be accessed around the world either as open domain files or through special archives. This means information that has either laid unseen in a private collector’s library, or has only been accessible to a select few can now be accessed by the entire world. This tidal wave of new information is changing how we see the 18th century in numerous ways. A good example of this is the silk bonnet. Earlier it was commonly believed by reenactors that a silk bonnet was something that would have been out of reach to the “lower sort” of women in the 18th Now however, after searching through runaway ads here in America, looking at artwork from England, it’s clear that these beautiful articles of clothing were available to a much wider range of women than was originally supposed. Our knowledge of the 18th century is largely a collection of theories; strong theories mind you, and ones back up with multiple bits of data to support them. But as the data changes, our conclusions must change as well.

- IMAGINATION IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR KNOWLEDGE. Even without photographs, film, or with the amount of material culture items industrial-age historians are accustomed to there is a very large amount of source material and artifacts from the 18th There is no excuse for not making use of this material. When you choose an impression, be specific about what it is you’re trying to do. Are you doing a civilian or military? What nationality? What year and where are they? What is their social class? All of this is important. Military clothing, though it follows the fashions of the time, is distinct in many ways from its civilian counterparts. You won’t find examples of civilians in 1777 Philadelphia wearing gaitered trousers. The nation is important because every nation has their own idiosyncrasies. Time and place also play a factor. Fashions, like today, change with time.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Social class is also of major importance. Some clothing item are compatible to some extent across the classes. For instance, men’s shirts of the day are universally of a good quality in terms of stitch work (though they are often made of different grades of material). In other ways they’re very different. A laborer isn’t likely to be wearing a silk coat and breeches. Likewise, a gentleman isn’t likely to have an osnabrig (a kind of course natural linen) shirt and the same clothing items as a private soldier in the army (any army). Doing any impression costs money. To do a higher class impression well costs more money, just like how it’s easier to get a suit from Boscov’s (like me!) than to have one tailored to your desires in London or L.A.

- QUALITY IS A QUANTITY ALL ITS OWN. This is the last point I want to make. I’m immensely proud of my impressions, of which I have two…and a half. I have a 17th Regiment soldier’s kit, a kit for the Philadelphia Associators, and a mostly finished civilian impression. I say “mostly finished” because my coat is sitting sleeveless and partially un-lined on a chair. The reason I’m immensely proud of my kit is that I’ve made much of the clothing items I possess. My 17th Regimental and its waistcoat were the first 2 sewing projects I’d ever done. The things that I didn’t make were made by friends of mine who are very skilled at their trades. That’s what makes a good 18th century impression. Clothing of the time was done by hand, not machine, and most men’s clothing is fitted. You can see this in the paintings and sketches of the time. Clothing was expensive for these people, and they took care of what they had. They also dressed as well as they could. You should, too. If you’re new to this period, or reenacting in general, my advice for you is this. If you’re thinking of buy “off the rack” clothing, don’t. Save your money. Reenacting isn’t going anywhere. There are people out there who will take your measurements and whip you up a set of period clothing. Many of them are really good, and naturally they charge for that service. It might take you time to get that money together but the quality will be worth it and you won’t have to go and buy a better piece of clothing down the road.

If you have an aptitude for sewing however, or you can get with a group of people who know how to sew and can teach you, then you’re life probably just got a lot easier. With the right patterns for your clothing, patience, and help, you can make your own clothing for a much more agreeable sum of money. On top of that, you learn a valuable skill. And once you can sew, you can make yourself into anyone!

The study of history and the recreation of it is a noble hobby. But to do it right takes work, research, money and commitment. But most importantly, it takes networking with good people. That’s how I have learned so much, and really it’s the people we hang out and work with that make this hobby so great.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.