A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution part 2

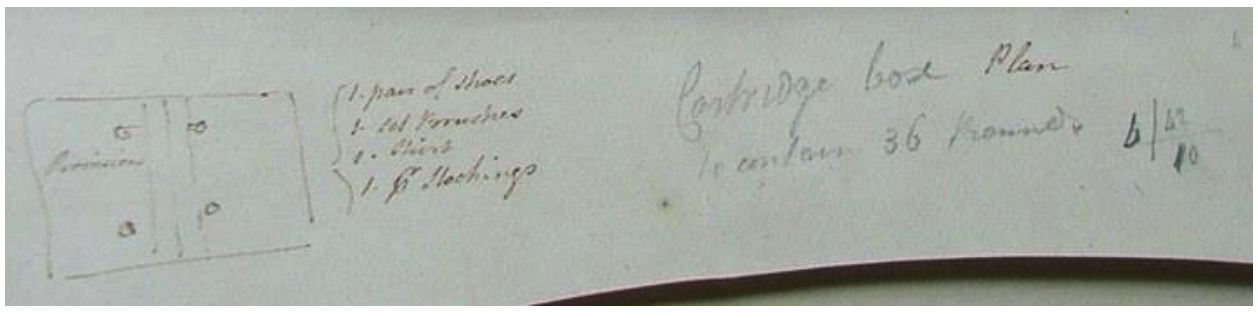

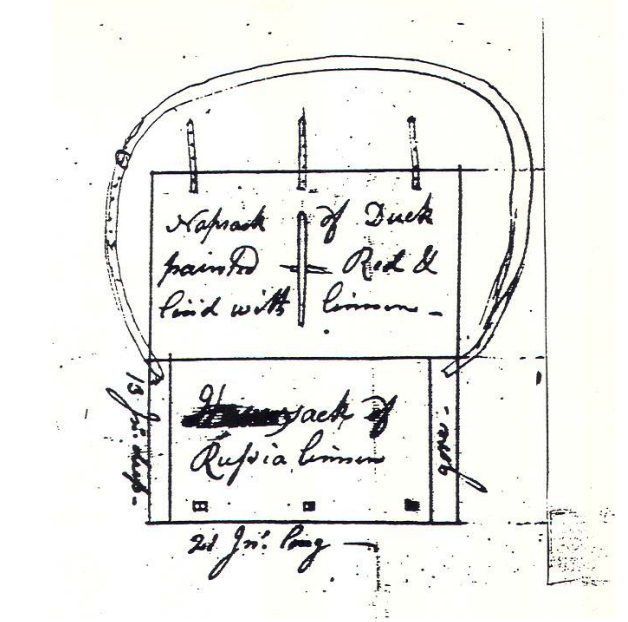

While we may never learn the answers to the aforesaid questions, here are several things we do know or think we know. First, we look at a crucial clue in this discussion, but one that is accompanied with some uncertainty and a caveat or two. The first known image of a British double-pouch knapsack (see below) was found in a 71st Regiment manuscript book titled “Standing Regimental Orders in America”; the first half of the volume contains standing orders for 1775 (before the regiment arrived in North America), the second half entries for 1778, beginning 3 June and ending with a 24 August order. The context of the knapsack image is difficult to ascertain but, in my opinion, was likely done in 1778. A caveat – while we can assume it portrays a piece of British equipment, the possibility of the image showing a captured item remains in the realm of possibility. That possibility seems to be lessened by the absence of a descriptor noting such. Added to that, there are indications the British went into the war using single-pouch knapsacks, the 71st order book drawing, likely dating to 1778, being the earliest evidence for the double-pouch variety.

Next, a known item with a supposition attached to it. In February 1776 a contractor sent a proposal to convince the state of Maryland to procure for their troops his “new Invented Napsack and haversack.” In the end numbers of his knapsack were made and issued to several Maryland units, and probably some Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops. Though impossible to prove, an intriguing possibility is that the new British knapsacks were inspired by the American “Napsack and haversack,” a not unreasonable contention given the similarity in design and that the 71st knapsack drawing also shows one pouch designated to carry food.

From 1776, we move four years ahead, to Benjamin Warner’s service with Col. John Lamb’s 2d Continental Artillery Regiment. Given that his other tours, from 1775 to 1777, were with state or militia units, and given what we know of America knapsacks during those years, it is most likely his extant knapsack dates from his 1780 stint. Warner’s pack may have been copied from captured British equipment. The practice did occur, perhaps the best known instance being the Continental Army twenty-nine round “New Model” cartridge pouch, copied from British pouches taken with Burgoyne’s troops and first made in Massachusetts in the winter of 1777-78.

(See following page for images of the Warner knapsack.)

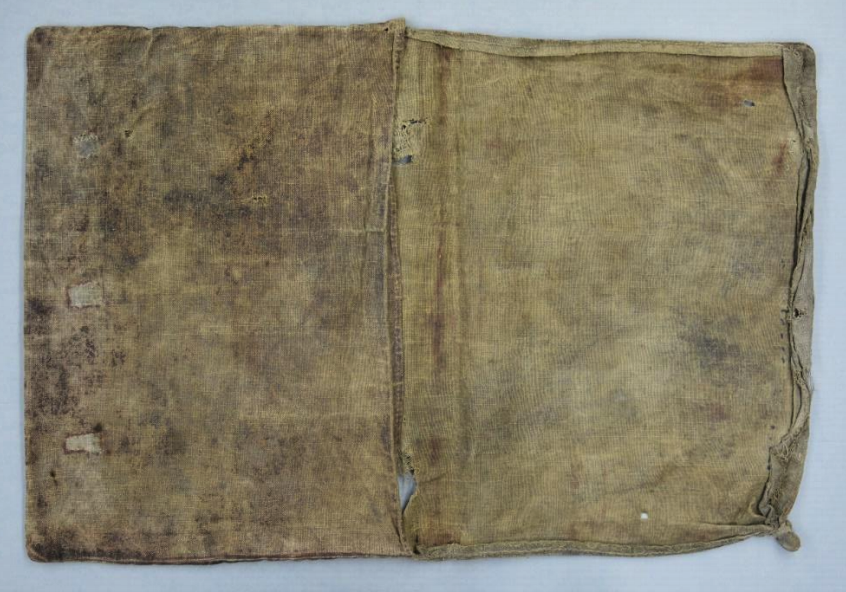

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack.

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack. While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

"I observe in your return the mention of upwards of three thousand yards of oznaburghs Tho' this kind of linen is not the best for knapsacks yet they have very commonly been made of it. Of that in your possession I wish you to select immediately the best, & to have one thousand knapsacks made up. They should be made double, & one side painted with the cheapest paints. I will furnish you with Mr. Morris's notes to enable you to pay for this work which cannot cost much. Be pleased to have the knapsacks made with dispatch & forwarded without delay to Colo. Hughes."

Numbered Record Books, National Archives, 1780-July 9, 1787, vol. 26.Timothy Pickering to Peter Anspach, 23 April 1782:

"Desire Mr. [Mery?] to examine the bolts of oznaburghs which came from Virginia, and pick out those fittest for knapsacks, & get as many made as he can: If he would cut out one of a proper shape, he could get some careful woman to cut out the residue, & employ other women to make them up. Let them be made double, & one side painted. Perhaps all the oznaburghs will answer as well as those knapsacks usually made. There are some here which were left or rather contracted for by Col. Mitchel, that are wretched indeed: I think any of our oznaburghs better by far."

Miscellaneous Numbered Records (The Manuscript File) in the War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records 1775–1790's, National Archives Microfilm Publication M859, (Washington, D.C., 1971), reel 87, item no. 25353.

Also in 1782, Pierre L’Enfant, captain Corps of Engineers, painted a panorama of West Point. To one side are two groups of Continental troops, including several soldiers wearing rolled blankets atop their knapsacks, the first images showing that being done.

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"]

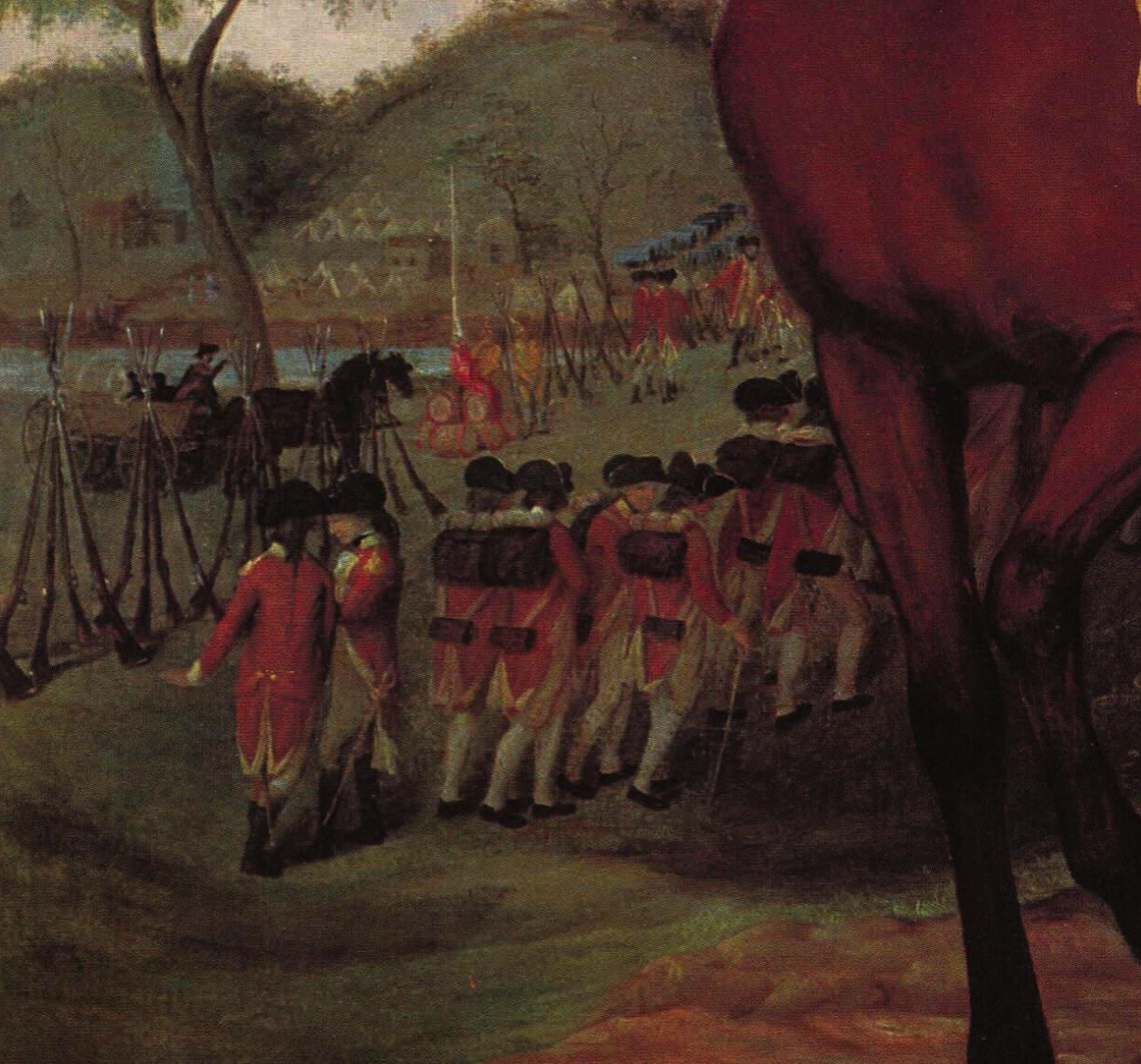

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"] Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .Read Part 1 of A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution Here !