Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

Our Officers and Men Behaved Like Men Determined To Be Free

The Battle of Stony Point, Recreated

The night of July 15th, 1779 may have started out as a perfectly normal evening for the roughly 500 British soldiers and 70 women and children stationed at Stony Point. It would erupt into musketry and the clash of steel as American troops would surge over the earthworks.

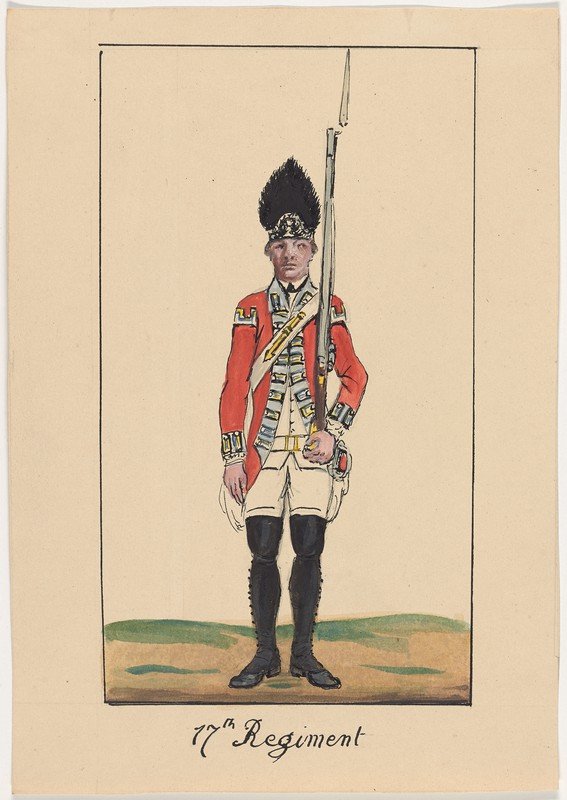

“The works were manned by eight companies of the 17th Regiment of Foot, which had arrived in America in 1775 and were veterans of many of the major battles fought thus far; two companies of grenadiers from the 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser’s Highlanders), another veteran regiment; sixty-nine men of the Loyal American Regiment, a regiment of Loyalists whose colonel lived twelve miles north of Stony Point; and a number of servants and artisans. In all, the garrison of Stony Point amounted to 564 men.” [2]. These men would be stacked against some of the finest troops the Congressional Army had to throw at them: Anthony Wayne's newly raised Corps of Light Infantry, consisting of four regiments of American troops drawn from all over the States. While the end goal was to secure a vital ferry crossing the Hudson, many consider this battle to be the beginning of the end of the American War of Independence.

The battle was short and brutal. Three columns would carry out the assault: one under the charge of Colonel Butler of Pennsylvania, one with Anthony Wayne, and a third column set out to act as a diversion under the command of Major Hardy Murfree.

Wayne's men set up on the north and south approaches into the post with Murfree in the center with his men. The assault began with Murfree's men firing into the works. The “Forlorn Hope” stormed forth with axes, cleared the abatis, and stormed into the British lines. The columns follow suit, charging forth with bayonets fixed.

As Anthony Wayne led his column up towards the works, he was struck in the head by a musket ball, grazing him but sparing his life. Febiger accepted the surrender on behalf of the American Forces, and the battle is over. [2]

This July we are hoping to recreate what is considered by many to be the “beginning of the end of the American Revolution”. From July 12-14th, American and British reenactors will gather at the Point and try our best to recreate what life might have been like for these men and women.

British forces will have the opportunity to fortify, laying out abatis and wooden fortifications. Women following the army will launder, mend, and ply their trades in the British held position. We hope to recreate what garrison life might have been like for these troops as realistically, accurately, and honorably as possible.

American forces of stout mind and body will be spending Friday a few miles away at Fort Montgomery. They will recreate the night before the assault: mastering the drill, preparing food, and seeing to their laundry and mending rendered by the American followers. Early Saturday morning, the American forces will march along the historical route of march to Stony Point! Fourteen miles through the woods and across the mountains.

The event is shaping up to be one of the best of this year. Reenactors as far west as Iowa, as far north as Maine, and as far south as the Carolinas are coming out to tell the story and bring to life those chaotic days in 1779.

Footnotes:

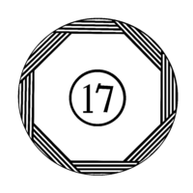

- Map of Stony and Verplanck Points on the Hudson River as fortified by Sir Henry Clinton June. [?, 1779] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71002308/.

- Anderson, Eric. ""Our Officers and Men Behaved Like Men Determined To Be Free": The Battle of Stony Point, 15-16 July 1779." The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army. July 16, 2018. https://armyhistory.org/our-officers-and-men-behaved-like-men-determined-to-be-free-the-battle-of-stony-point-15-16-july-1779/.

- James Peale, Major-General Anthony Wayne, ca. 1795, watercolor on ivory, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Mary Elizabeth Spencer, 1999.27.41

HAYDEN CONLEYJoseph Hayden Conley is currently attending Eastern Michigan University, pursuing a BA in Secondary Education History, He is an avid historian, with a particular love of American Light Infantry during the American Revolution and New Jersey troops during the American Revolution. He has worked for Fort Ticonderoga, as well as Mackinac State Historic Parks in Michigan. He has been apart of the living history community for over 10 years, and is a member of the 3rd New Jersey, Captain Bloomfields Company.

HAYDEN CONLEYJoseph Hayden Conley is currently attending Eastern Michigan University, pursuing a BA in Secondary Education History, He is an avid historian, with a particular love of American Light Infantry during the American Revolution and New Jersey troops during the American Revolution. He has worked for Fort Ticonderoga, as well as Mackinac State Historic Parks in Michigan. He has been apart of the living history community for over 10 years, and is a member of the 3rd New Jersey, Captain Bloomfields Company.

Officers of the 17th Part Four- Choosing Sides in the American Revolution

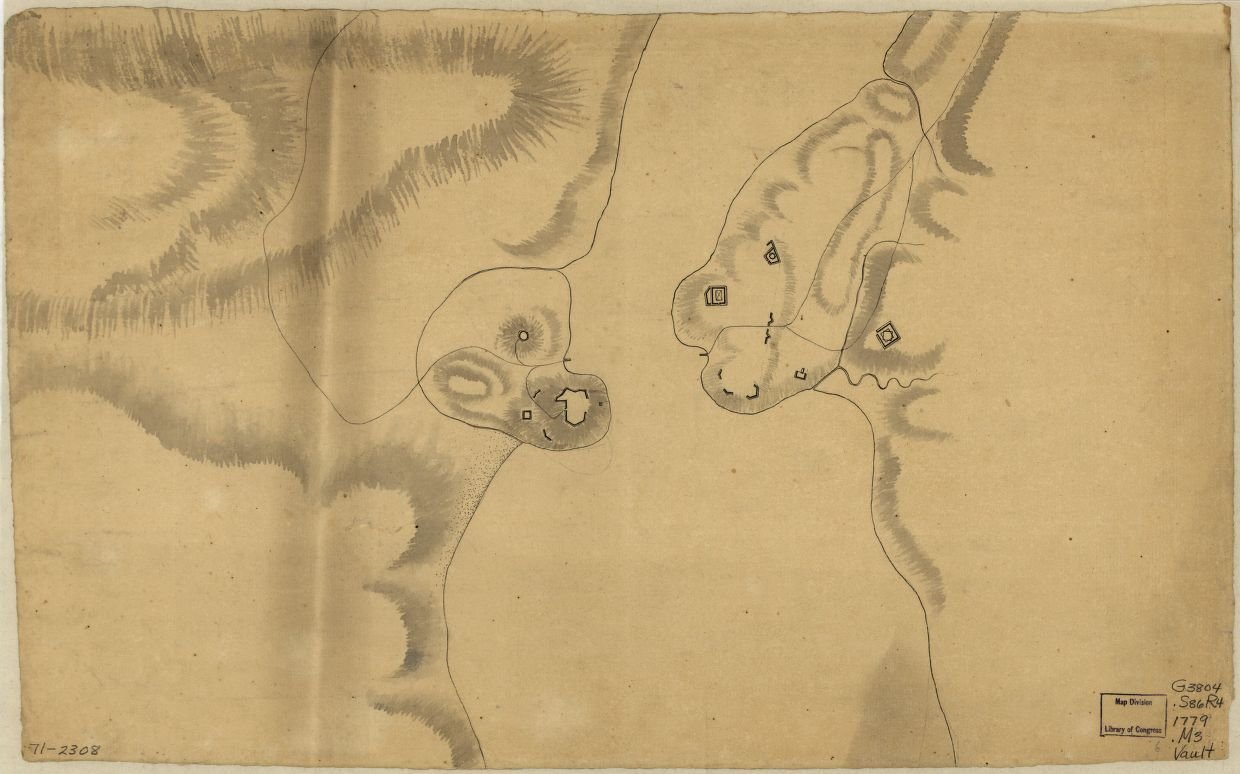

This entry will be a bit different, as it will tell the story of three retired officers of the 17th who had sought new lives in America in the 1760s and 70s, only to find themselves caught up in the turmoil of the American Revolution. Faced, like all residents of the American colonies, with difficult questions of loyalty and identity, these three reacted as variously as the broader population. Richard Montgomery, the best known of the three, enthusiastically embraced the Patriot cause and died a hero of the Revolution. James Howetson stayed loyal to his king and died trying to recruit men for a Loyalist unit. The sickly William Howard was a supporter of the Patriot cause married to a Loyalist wife, and sought to achieve domestic harmony by avoiding the subject.

First, some background. With a major commitment of British regulars to North America during the Seven Years War came increased contact between its officers and the colonial world. The elites of the British army tended to mix with colonial counterparts wherever they were stationed, seeking the “society” of polite company among merchants, planters, and professionals. At the most obvious level, dance partners often turned into wives. The correspondence of British officers of the period mentions what General James Murray, writing in 1764 from Montreal, called the “Matrimonial Distemper”, and it is easy to find dozens of examples of officers marrying into the higher reaches of colonial society. Just a few- At the very top is the marriage of General Thomas Gage to Margaret Kemble of New York, while his military secretary, Captain Gabriel Maturin, married into the Livingston family, also of New York. Other examples include Major Pierce Butler of the 29th marrying a daughter of Thomas Middleton, a prominent South Carolinian and Arthur St Clair of the 60th, who married into the Bowdoin family of Boston when stationed there in 1760. (see John Shy, Toward Lexington, pp. 354-358).

A second, and often related, attraction of the colonies was the ready availability of land. Younger sons of the British gentry often sought to improve their economic positions by settling on American estates. Occasionally they were granted land by the government, but more often they were able to purchase estates by selling their commissions and using the proceeds, or by marrying into the prosperous colonial classes. Our first example, Richard Montgomery, did a bit of both.

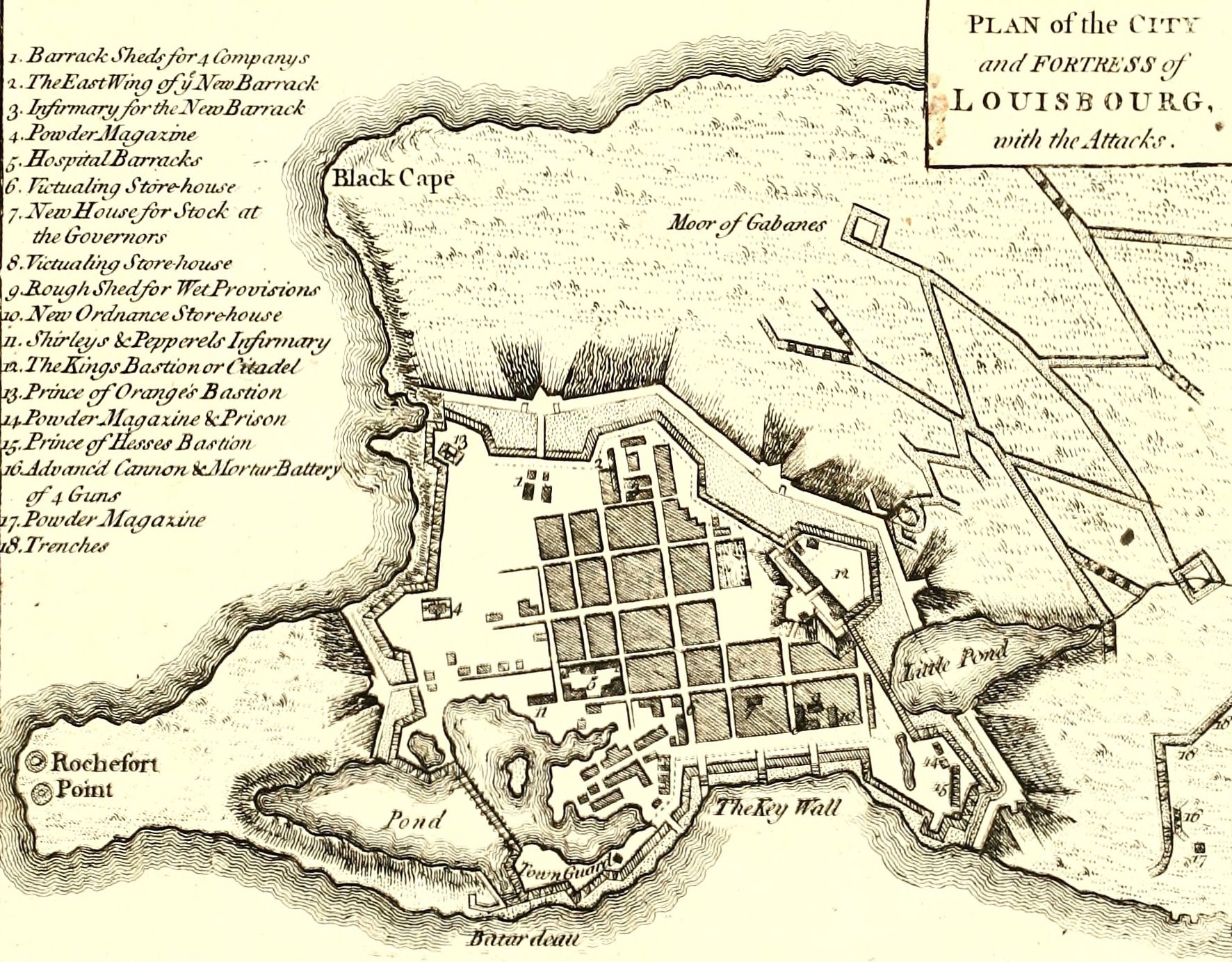

Richard Montgomery was born in 1738 into an Anglo-Irish landed family with a strong military tradition. His grandfather, father and older brother all served as officers in the army. Richard’s father, Thomas Montgomery, was disinherited from the family estate of Ballyleck when he married without permission, but nevertheless served as an MP for Lifford. Richard had a more extended education that most officers of the day, attending Trinity College, Dublin for two years before leaving university to join the 17th regiment. His father purchased his ensigncy for him on April 21, 1756 and Richard sailed to New York with the regiment the following year. He served through the siege of Louisbourg and, when a captain of the regiment was killed by a French sortie, was promoted to lieutenant without purchase on July 10, 1758. The 17th served in the successful siege of Ticonderoga the following year, though it appears to have been a troubled regiment. Personality conflicts among senior officers, abuse of enlisted men by officers and non-coms, desertion and indiscipline adversely affected the 17th’s performance during the early years of its service in America. The regiment began to improve in the later part of 1759 as several officers resigned and more competent ones advanced in rank. It is perhaps a sign of the professional stature of the young Richard Montgomery that he was appointed adjutant on May 15, 1760 on the court martial and dismissal of the previous adjutant. (see BLG of Ireland, 1904, p. 412, Montgomery of Beaulieu; George Montgomery, A History of Montgomery of Ballyleck; and Michael Gabriel, Major General Richard Montgomery, pp. 17-27.)

Following the conquest of French Canada the 17th participated in several grueling campaigns in the West Indies, with severe losses in the unhealthy islands. Montgomery was at the capture of Martinique and Havana, purchasing his company on May 4, 1762. The sickly remnant of the regiment returned to New York in August of that year, and spent nine months recruiting and recovering. Montgomery was among the sick, later recording that the climate of Cuba “made him lose a fine head of hair.” The regiment then served in Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763-4. Montgomery finally returned to Europe on leave after six years of service in America, having campaigned and travelled over much of the middle colonies and Canada and with a wide circle of acquaintances among New York’s elites. (Gabriel, pp. 28-36).

Peacetime soldiering did not agree with Captain Montgomery. Frustrated with repeated unsuccessful attempts to purchase his majority and with few opportunities to excel at his profession, he eventually decided to leave the army. In 1772 he wrote to his cousin “You no doubt will be surprised when I tell you I have taken the resolution of quitting the service and dedicating the rest of my life to husbandry….And as a man with little money cuts but a bad figure in this country among Peers, Nabobs, etc, etc, I have cast my eyes on America, where my pride and poverty will be more at their ease.” Magill Wallace, a fellow officer in the 17th, Montgomery’s close friend, and related to a family of New York merchants, purchased his captaincy for over 1500 pounds. The sale of his commission and his properties in Ireland gave Montgomery the money to get started on his new career in America, and he purchased a farm in Westchester County, New York by the spring of 1773. He married Janet Livingston, a member of one of the most powerful landowning families of New York, in July of that year, thus entering the highest circles of New York provincial society. (Gabriel, pp. 40-59)

As the series of crises leading to the American Revolution forced New Yorkers to take sides, the Livingstons emerged as leaders of the Patriot faction. Richard Montgomery was probably predisposed to sympathize with the Patriot cause, as he was familiar with similar struggles playing out amongst Ireland’s Protestant elites during the same period. Still, it was a gradual process for him. Though his sympathies lay with the Patriots, he also remained attached to his old comrades of the 17th. He continued to correspond with Perkins Magra, writing him in 1774 that he “entertain[ed] a more cordial regard [for the officers of the regiment] than I shall probably ever again feel for any of my fellow creatures.” Initially reluctant to engage in politics, he was selected as a delegate to the provincial congress in May of 1775. When the Continental Congress appointed George Washington as commander of the American army in June and sought out other experienced military men to act as his subordinates, Richard Montgomery was appointed a brigadier general in the new Continental army. (Gabriel, pp. 70-82).

I will give only a brief summary of his career in the American army, as his story is well known and extensively covered elsewhere. Montgomery’s served on the Canadian front, revisiting much of the ground he had campaigned over during his years in the 17th. Serving under Philip Schuyler, he helped organize the northern Continental army and was second in command as it commenced the invasion of Canada. He then commanded the army during the two month siege of St Johns, capturing it on November 3, 1775, then marched into Montreal ten days later. He led his undisciplined, sickly and poorly supplied army on to Quebec City, and died leading it in a desperate assault on the town on December 31st. Richard Montgomery became one of the earliest heroes and martyrs of the American Revolution, and was celebrated in paintings, poetry and plays. (Gabriel, chapters five through eight).

My second subject was far more obscure. James Howetson (also Hewetson, Huston) was born in Scotland circa 1736 and joined the 17th as an ensign without purchase on April 29, 1762. He served in the final campaigns of the war and in Pontiac’s Rebellion and was with the regiment until he retired in 1769. A number of sources describe him as a half pay lieutenant, but I have found no evidence that he was on the half pay list or reached the rank of lieutenant. He settled in New York after leaving the regiment and married Engeltje Wendell in 1772. His wife belonged to a family of German descent long settled around Albany and Schenectady. At the outbreak of the Revolution he was living in Lunenburgh (present day Athens, Greene County, New York). Other sources list him as a resident of nearby Coxsachie. As a former British officer he was suspected of Loyalist sympathies and the Albany committee of safety forced him to sign a parole on April 30, 1775. Howeston promised to stay near his home, talk with no other Loyalists and take no action against the Revolution. He first violated his parole by helping to set up a Loyalist communication network, and received a warning from the committee. He seems to have received several other warnings, including an order to desist in recruiting for Loyalist units.

In late 1776 or early 1777, Howetson was appointed to a secret commission as captain to a loyalist battalion being raised on Livingston Manor by New York Loyalist Sir John Johnson. The large manorial estates of the Livingston family had long been a site of tension between the great proprietors and their tenants. The Livingstons, as mentioned above in Richard Montgomery’s sketch, sided with the Patriot cause, and their dissatisfied tenants tended to side with the British, hoping a Loyalist victory would lead to land reform and better economic conditions. Howetson and other Loyalists and former British officers attempted to raise a Loyalist unit among the tenants of Livingston Manor. In May of 1777 some five hundred of them gathered, hoping to join the British forces advancing from Canada. Patriot militia reacted promptly and crushed them at a skirmish known as the “Battle of Jurry Wheelers” on May 2. Many were jailed for a time, and two, including Howetson, were sentenced to death. Howetson was charged with treason for recruiting for the enemy while a citizen of New York. He seems to have been regarded as a man who was particularly culpable as he had violated his parole several times, and had been warned to cease recruiting. His court-martial, held on June 14, 1777, sentenced him to be hanged. He was executed at Albany either on July 4 or sometime in August. (see Harry Ward, The War for Independence and the Transformation of American Society (1999), p. 43; Philip Ranlet, The New York Loyalists (1986) pp. 130-2; Loyalist Trails UELAC Newsletter, 2005, biographical sketch by Gavin Watt; New York Marriages; Schenectady Digital History Archive, Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs: Wendell).

Our third officer sided with the Revolution but seems to have been too decrepit to do much about it. William Howard was born in England circa 1720. Some family historians have attempted to link him with the great northern landowners of Yorkshire and Cumbria, the Howards, Earls of Carlisle, but there is no real evidence about his family background. He was commissioned as an ensign in the 17th on July 5, 1735, became a lieutenant on April 25, 1741, became adjutant to the regiment in 1746, became a captain lieutenant on April 17, 1756 and purchased his captaincy on Nov. 22 of that year. Howard travelled to America with his regiment and served throughout the Seven Years War. One of the few glimpses of him on campaign that I have found occurred while he was part of the force besieging Fort Ticonderoga in July of 1759. On the night of July 26 the French garrison withdrew from the fort and attempted to destroy it by blowing up the powder magazine. The explosion resulted in a shower of rocks on parts of the British line and several companies of the 17th panicked and abandoned their posts. Several officers were court-martialed over the incident, including Captain William Howard. He was able to establish that he did his utmost to rally his men and bring them back to the line in good order, and was exonerated by the court. (WO71: 67, Court Martial of Captain William Howard, 30 July 1759).

![]()

The first hint of his interest in settling in America comes when the regiment was stationed in New York in September of 1763, when Howard requested leave “to go down to the Jersies on leave, his concerns…require his presence.” (WO34:53, f. 128 Campbell to Amherst Sept. 30, 1763). In June of 1767, on the eve of the regiment’s return to England, he applied to General Gage for permission to sell out, as his state of health no longer permitted him to go on active service. (Gage Papers, Clements Library, Gage to Howard June 27, 1767). He settled near Princeton in a house known as Castle Howard (thus abetting the confusion about his unlikely origins as a member of the British aristocracy), with 200 acres of land and some woodland. According to a post-Revolutionary War affidavit prepared by President Witherspoon of Princeton College, Captain Howard “lived in a genteel manner” and “was generally believed to be wealthy.” He married Sarah Hazard, most likely related to a merchant family with interests in New York and Philadelphia. (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, Vol. 9, p. 85 biography of Ibbetson Hamer; Recollections of Olden Times: Genealogies of the Robinson, Hazard and Sweet Families of Rhode Island, p.260)

Howard played a very small role in the Revolutionary crisis, though his views were well known to locals. According to tradition, he was a victim to gout and was confined to his room by 1776. While he was an ardent Patriot, his wife was an enthusiastic Loyalist, and insisted on entertaining British officers who passed through the community. The old veteran, forced to listen to their unwelcome political views, had painted over his mantel “No Tory Talk Here”. He died some time in 1776, and his wife promptly married another British officer, Ibbetson Hamer of the 7th Foot. Her property was confiscated in 1777 and she removed to England with her husband after the war. (above, and PCC Will of Sarah Hamer, November, 1821)

None of these three former officers survived the war. Montgomery sided with the Patriots, died in battle and is remembered as a hero of the Revolution. Howetson continued to serve his king, ignored repeated warnings to cease recruiting, and was hanged, a near forgotten victim of what was, in many respects, a civil war. Howard paid, perhaps, the smallest price, with the peace of his final years disturbed by trouble in his household.

DR. MARK ODINTZ PhD.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

DR. MARK ODINTZ PhD.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

Did you miss the beginning of this discussion? Find parts 1, 2, & 3! Linked there.

Follow-Up: “Like a Pedlar's Pack.”: Blanket Rolls and Slings

Part 3 to A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution Read Parts 1 & 2.

“Square knapsacks are most convenient …”

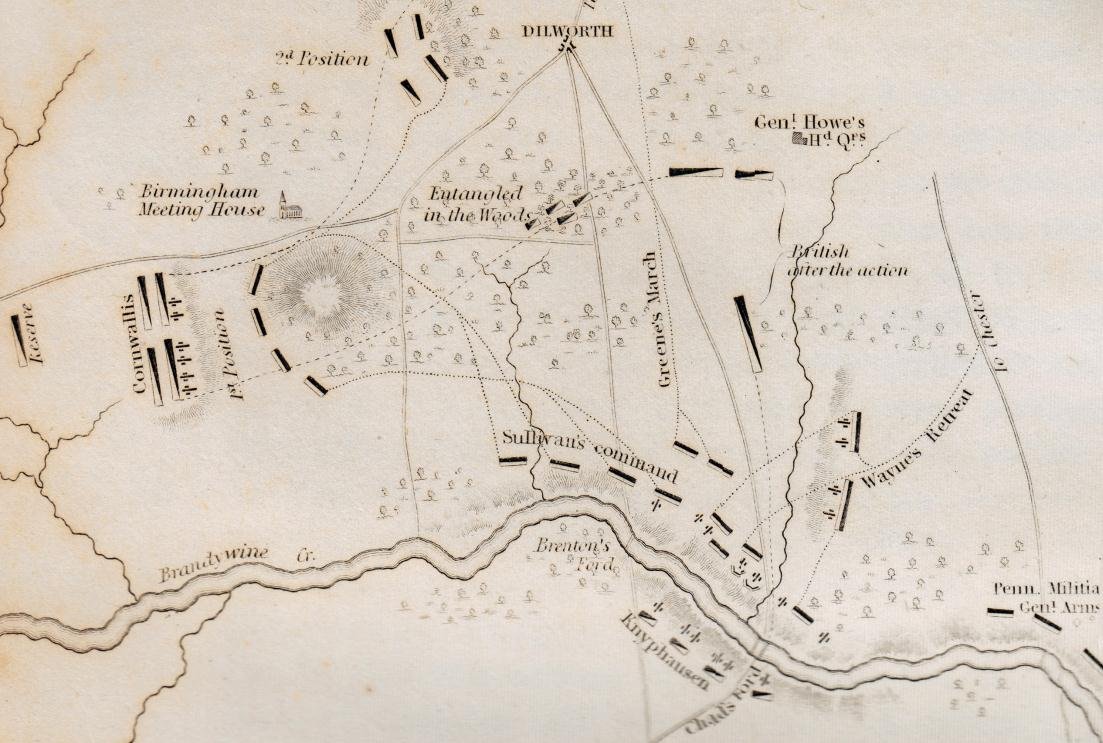

While British troops used blanket slings instead of knapsacks during several campaigns, one reason being the “ill Conveniency” of their packs (whatever that might mean), slung blankets had their own inconveniences, one of those being having to undo them every night and re-roll them before marching. Here we have American surgeon Dr. Benjamin Rush’s observations while tending to American wounded after the Battle of Brandywine:

One of the [British] officers, a subaltern, observed to me that his soldiers were infants that required constant attendance, and said as a proof of it that although they had blankets tied to their backs, yet such was their laziness that they would sleep in the dew and cold without them rather than have the trouble of untying and opening them. He said his business every night before he slept was to see that no soldier in his company laid down without a blanket."1

Welbourne Immersion Event 2015

Welbourne Immersion Event 2015

That said, British troops certainly used slings, and likely used rolled blankets slung over the shoulder, as well (see image of 25th Regiment soldier at Minorca, below). Here are a series of British narratives or general orders mentioning blanket slings, or occasions when blankets were to be carried without knapsacks.

84th Regiment, “point au Trimble,” Quebec, 18 August 1776, "Every Man to be pervided With a Topline [tumpline] if Wanted and to prade Opisite the Church, on Thursday Morning With thire Arms Accutements and packs, properly Made up as for a March.”2

Brigade of Guards, orders, 19 August 1776, "When the Brigade disembarks two Gills of Rum at most must be put into each Man's Canteen which must be fill'd up with Water. Every Man is to disembark with a Blanket, in which he is to carry three days provisions, one Shirt, one pair of Socks, & one pair of Shoes. A careful Man to be left on Board each Ship to take care of the Mens Knapsacks, if there are any Convalescents they may be order'd for this.”3

Capt. William Leslie, 17th Regiment of Foot, 2 September 1776, “"Bedford Long Island Sept. 2nd 1776… The Day after their Retreat we had orders to march to the ground we are now encamped upon, near the Village of Bedford: It is now a fortnight we have lain upon the ground wrapt in our Blankets, and thank God who supports us when we stand most in need, I have never enjoyed better health in my Life. My whole stock consists of two shirts 2 pr of shoes, 2 Handkerchiefs half of which I use, the other half I carry in my Blanket, like a Pedlar's Pack."4

Brigade of Guards, orders, 11 March 1777, "The Waistbelts to Carry the Bayonet & to be wore across the Shoulder. The Captains are desired to provide Webbing for Carrying the Mens Blankets according to a pattern to be Seen at the Cantonment of Lt. Colo. Sr. J. Wrottesleys Company. The Serjeants to Observe how they are Sewed. The Officers to Mount Guard with their Fuzees."5

40th Regiment orders regarding blanket slings, wallets, and contents, spring and summer 1777:6 After Regl Orders 7 at Night [10 May 1777]

A Return to be given immediatly from each Company to the Qr. Mr. of the Number of Shoe soles and heels wanting to Compleat each man with a pair to take with him the Ensuing Campaign

The Regt. to parade to morrow Morning at 11 oClock with Arms, Accoutrements & Necessarys in order to be inspected by their Officers -- The Necessarys to be carried in their Wallet and slung over the Right Shoulder --

R[egimental]:O[rders] 14th May 1777

Each Compy. will immediately receive from the Qr. Mr. Serjt. 26 Slings & Wallets to put the quantity of Necesareys Intendd. to be Carrid. to the field Viz 2 shirts 1 pr. of shoes & soles 1 pr. of stockings 1 pr. of socks shoe Brushes, black ball &c Exclusive of the Necessareys they may have on (the[y] must be packd. in the snugest manner & the Blankts. done neatly round very little longer than the Wallets) to be Tyed. very close with the slings and near the end -- the men that are not provided. with A blankett of their own may make use of one [of] the Cleanest Barrick Blanketts for to morrow –

After Regl. Orders 7 at Night [18 May 1777] …

The Regt: to parade to morrow Morning at 11 oClock with Arms, Accoutrements & Necessarys in order to be inspected by their Officers – The Necessarys to be carried in their Wallet and slung over the Right Shoulder … The pipe Clay brought this day from Staten Island to be divided in eight equal parts and each Company to get a dividend it is hoped the Compys: will make better use of this then thay did of the last

[Regimental Orders, 23 May 1777] … The Non Commissd: Offrs: and Men to have their Necessareys Constantly packd: in their Wallets ready to sling in their Blanketts which they are to parade with Every morning at troop beating to Acustom them to do it with Readiness and Dispatch The men of the Qr:Gd: to parade when the taps beat to be properly inspectd: and ready to march of[f] Immediately fter the troop has beat –Morn.g Regl. Orders 2d June 77 …

Black tape to be provided immediately to tie the Mens Hair -- NB It is to be had in Amboy. -- The Mens Hair that is not properly Cut to be done this Day -- Each Company to give in a Return to the Quarr. Masr. of the Number of Wallets & Slings wanting to Compleat each Man as the whole must have them to appear uniform in the slinging on & Carrying their Blankets & Necessarys -- Any of the Wallets or Slings not properly made to be returned to the Masr. Taylor –

R[egimental]:O[rders] [9 June 1777] …

The Commanding Offrs: of Comp[anie]s. are Immediately to settle their Accompts With the Qr: Mr: for the under Mentiond Articles According to the following rates at 4 [shillings]:8d pr Doller

Trowzrs: making &c ....................... £ 4:2 1/2Wallets & Slings. ......................... 2:2 1/2Coats Cuting & Mending when at Hallafax..... 4 1/2Do: Do: at Amboy .......................... 10Diffeichinceis on Breeches clothwhen at Staten Island. ................ 4 1/2 Do: on Leggons ............................. 349th Foot, "Regimental Order on Board the Rochford 21 August 1777 When the Regt. Lands

Every Non Commissd Officer and soldier of the Regiment is to have with him 2 very good Shirts, Stokings, 2 pair Shoes, their Linin drawers, Linnin Leggins, half Gaiters and their Blankets very well Rold. Every thing to be perfectly Clean. Officers Commanding Companies will be answerable to the Commanding Officer that these orders are Strictly Complyed with-“7

Guards, “Brigade Morning Orders 30 August 1779 The Qr. Masters are desir'd to be as expeditious as possible in processing proper Bedding &ca from the Bk. Mr. Genl.-- & Field Blankets from the Qr. Mr. Genl. for the Draughts received from England.-- & to deliver to them from the Regl. Store a proper proportion of Camp Kettles, Canteens & Haversacks.The Companies are desir'd to Compt. their Draughts with proper Straps to Carry their Blankets, & to be as expeditious as possible in Compleating them with Trowsers."8Brigade of Guards, “1st Battn Orders 9 September 1779 The Men lately Joind having received their Field Blankets, the Serjts. are Ordered, to see that they are Mark'd with the Initial Letters of each Mans Name. The Men are to be provided with proper Straps for Carrying them & Shewn how to Roll them up.9

Lt. Gen. Charles Earl Cornwallis’s army, South Carolina, 1780 and 1781:10

On board ship off of Charlestown, South Carolina, 15 December 1780.General orders:

"The Corps to Compt. their Men with Camp Hatchets Canteens, & Kettles ... It is recommended to the Comdg Offrs. of Regts. to provide the Men with Night Caps before they take the Field."

Brigade orders:

"The Necessaries of the Brigde. are to be Imdy. Comptd. to 2 Good pr. Shoes, 2 Shts. & 2 pr. Worsted Stockgs. per Man ... Each Mess to be furnish'd with a Good Camp Kettle, & every Man provided with a Canteen, & Tomahawk - & the Pioneers wth. all kind of Tools. The drumrs. are to carry a good Ax Each & provide themselves with Slings for the Same."

General orders, Ramsour's Mills, 24 January 1781:

"When upon any Occasion the Troops may be Order'd to March without their Packs; it is not intended they Should leave their Camp Kettles and Tomahawks behind them."

Brigade orders, 24 January 1781:

"There being a Sufficient Quantity of Leather to Compleat the Brigade in Shoes ... It is recommended to ... the Commandg. Officers of Companies, see their Mens Shoes immediately Soled & Repaired, & if possible that every Man when they move from this Ground take in his Blankett one pair of Spare Soles ..."

43rd Regiment, Virginia,"Apollo Transport Of[f] Brandon James River 23rd May 1781 …The Quarter Master will issue Canteens Haversacks and Camp Kettles to the Battalion immediately. The Companies to send Returns for their Effectives as this is the only supply the Regiment can possible Receive during the Campaign the Soldiers cannot be to careful to preserve them.Five Regimental Waggons will land with the Regiment. One to each Grand Division the fifth for Major Fergusons Baggage.The Quarter Master will issue an equal proportion of the Trowzers, made since the Embarkation- to each Company to compleat them as near as possible to Two pair per Man.It is positively Ordered that no Soldier lands with more necessaries than his Blanket, Canteen,Haversack, Two pair of Trowzers, Two pair of Stockings, and Two Shirts, and Two pair of good Shoes. The Remaining Necessaries of each Company to be carefully packed up and Orders will be given as soon as possible for its been taken proper care of."11

Footnotes:

- H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, vol. I (Princeton, N.J., 1951), 154-155.

- 84th Regiment order book, Malcolm Fraser Papers, MG 23, K1,Vol 21, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Orderly Book: British Regiment Footguards, New York and New Jersey," a 1st Battalion

Order Book covering August 1776 to January 1777, Early American Orderly Books, 1748-1817, Collections of the New-York Historical Society (Microfilm Edition - Woodbridge, N.J.: Research Publications, Inc.: 1977), reel 3, document 37.

- Sheldon S. Cohen, "Captain William Leslie's 'Paths of Glory,’" New Jersey History, 108 (1990), 63.

- "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" (actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st

Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day the Brigade for American Service was formed), Manuscript Department, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.(Courtesy of Linnea Bass.)

- British Orderly Book [40th Regiment of Foot] April 20, 1777 to August 28, 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 6 (Military Papers, 1755-1798), vol. 1, reel 117. See also, John U. Rees, ed., "`Necessarys

… to be Properley Packd: & Slung in their Blanketts’: Selected Transcriptions 40th Regiment ofFoot Order Book,” http://revwar75.com/library/rees/40th.htm

- "Captured British Orderly Book [49th Regiment], 25 June 1777 to 10 September 1777, . George Washington Papers (microfilm), series 6, vol. 1, reel 117.

- "Orderly Book: First Battalion of Guards, British Army, New York" (covers all but a few days of 1779), Early American Orderly Books, N-YHS (microfilm), reel 6, document 77.

- Ibid.

- R. Newsome, ed., "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781", North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX (January-October 1932), no. 2, 178-179; no. 3, 286, 287.

- Order book, 43rd Regiment of Foot (British), 23 May 1781 to 25 August 1781, British Museum, London, Mss. 42,449 (transcription by Gilbert V. Riddle).

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .

Bands of Music in the British Army 1762-1790. Part 3

In the previous two postings, we've looked at what a band was, who were in them, what types of music a band played, and what kind of ceremonies they played at. Perhaps most interesting to those lovers of material culture and military uniforms is what these bandsmen wore.

The uniform of a bandsman varied depending on the regiment. These men were not drummers and fifers so the rule of reversed facings does not apply to them. Ultimately, the uniform of the band was left up to the officers paying for them. One way to see what they wore is through deserter ads. This first one comes from our very own 17th:

Deserted from his Majesty’s 17th regiment of foot, quartered in Perth, John Humphreys musician, aged twenty years, size five feet six inches one-half, very swarthy complexion and jet black hair, black eyes, hollow cheeks, has a stoop in his shoulders, slender bandy limbed, has a very hoarse voice, talks thick, plays well on the French horn and fife; had on when he deserted the musician’s uniform of the regiment, viz. a scarlet frock, with white cap [sic - cape] and cuffs laced with silver, with white buttons having the number of the regiment, white cloth waistcoat and breeches, silver laced hat. He was apprehended (but escaped) on Wednesday the 7th in the Canongate; had on a bonnet, black coat, and wore a long staff in his hand.[13]

It's important to note that the bandsman is not in reverse facings. These men were not drummers and fifers and were not held to the same rule that made them reverse colours. For most regiments, the bands simply kept the same colour coats as the enlisted and officers. The band of the 22nd Regiment did the same as the 17th. Their band wore red coats with the regiment's buff facings, buff waistcoats and breeches.[14]

Another deserter ad from the 21st Regiment or Royal North British Fusiliers describes:

JOHN GRANT, aged 23 years, 5 feet 2 3/4 inches high, born in Beverly, in Yorkshire, England, by trade a jockey, has brown hair, grey eyes, fair complexion, a little pitted with the smallpox, and very thin made; had on, when he deserted, his uniform blue jacket, turned up with a red cape, and cuffs. Whoever apprehends and secures the above deserter, shall, by giving proper notice to Captain NICHOLAS SUTHERLAND, Commanding Officer of the said regiment, at Philadelphia, receive ONE GUINEA reward, over and above what is allowed by Act of Parliament for apprehending deserters.

N.B. He is supposed to be gone to Maryland, as he has a wife and a plantation in that province.[15]

The most interesting fashion trend of the 18th century comes from the Turks. Janissary clothing and g became incredibly popular in bands of music. Cymbals and jingling johnnies, long poles with numerous bells, became common sights. In the image below attributed to Thomas Rowlandson, the drummer and the cymbal both wear turbans in the Janissary fashion.[16]

An even more striking example Janissary fashion is exhibited in the portrait of John

Fraser, a percussionist in the Coldstream Guards. He wears a large turban with feathers sticking out of it. His red coat features silver lace and tassels. His sleeves are red in the upper arm but turns into a white fabric. His instrument, the tambourine, is a direct import from Janissary music. Bands of music were integral to the martial music of the British Army. Stemming from the Harmoniemusik movement of the 18th century, regiments adapted the instrumentation to fit their needs. The talented soldier/musicians of these bands played everything from military marches to operatic symphonies. To set them apart from soldiers and drummers, their uniforms reflected the tastes of their officers as well popular movements in late 18th century pop culture.

Fraser, a percussionist in the Coldstream Guards. He wears a large turban with feathers sticking out of it. His red coat features silver lace and tassels. His sleeves are red in the upper arm but turns into a white fabric. His instrument, the tambourine, is a direct import from Janissary music. Bands of music were integral to the martial music of the British Army. Stemming from the Harmoniemusik movement of the 18th century, regiments adapted the instrumentation to fit their needs. The talented soldier/musicians of these bands played everything from military marches to operatic symphonies. To set them apart from soldiers and drummers, their uniforms reflected the tastes of their officers as well popular movements in late 18th century pop culture.

When the 23rd Regiment was inspected on May 27, 1768, Major General Oughton said:

"The band of Musick very fine. The whole perfectly well cloathed and appointed."[17]

After John Rowe attended the concert of Fife Major McLean in Boston, he wrote in his diary that;

"there was a large genteel Company & the best Musick I have heard performed there."

These bands were designed to impress their officers and audiences from the songs and instruments they played down to the lace on their coats.[18]

Footnotes: [13] Edinburgh Advertiser, 9 October 1772. Courtesy of Don Hagist[14] Don Hagist, "Notes on Bands of Music in the British Regiments," Originally published in The Brigade Dispatch, Volume XXVII, No. 1 (Spring 1997), pp. 17-19.[15] Pennsylvania Gazette, December 12, 1771. Courtesy of Don Hagist[16] For further reading on Turkish influence on European society, see Edmund A. Bowles, "The Impact of Turkish Military Bands on European Court Festivals in the 17th and 18th Centuries, " Early Music 34, no. 4 (2006): 533-59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137306. Raoul F. Camus, Military music of the American Revolution, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977[17] Sherri Rapp, British Regimental Bands of Musick: The Material Culture of Regimental Bands of Music According to Pictorial Documentation, Extant Clothing, and Written Descriptions 1750-1800, Accessed September 4, 2017, https://www.scribd.com/presentation/215381883/British-Bands-of-Musick[18] John Rowe, Anne Rowe Cunningham, and Edward Lillie Pierce, Letters and Diary of John Rowe: Boston Merchant, 1759-1762, 1764-1779, Boston, MA: W.B. Clarke Co., 1903, Page 185, Accessed September 3, 2017. https://archive.org/details/lettersdiaryofjo00rowe

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

Read Part 1 and Part 2! This is the final part in a 3 part post.

A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution part 2

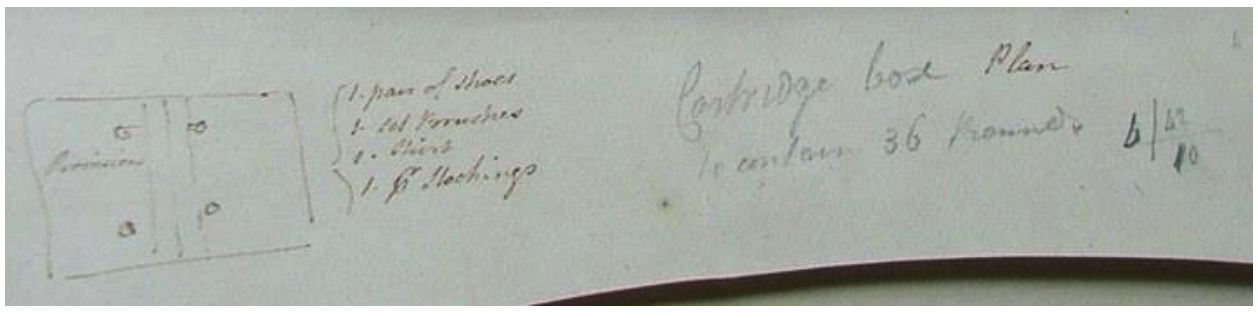

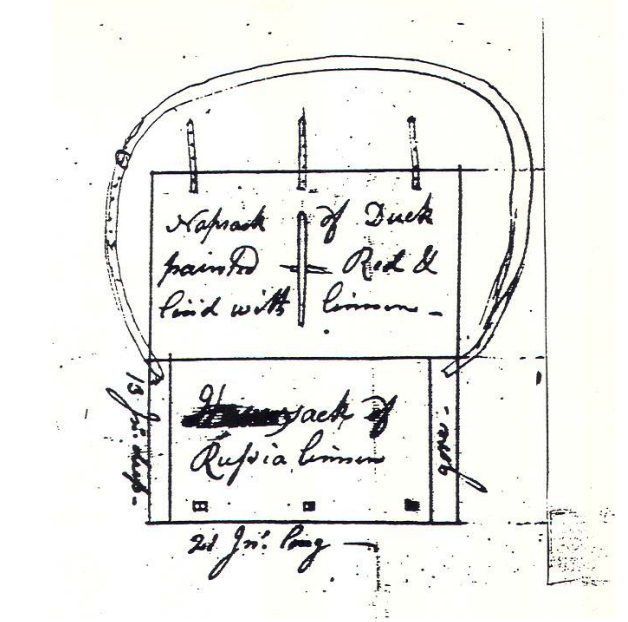

While we may never learn the answers to the aforesaid questions, here are several things we do know or think we know. First, we look at a crucial clue in this discussion, but one that is accompanied with some uncertainty and a caveat or two. The first known image of a British double-pouch knapsack (see below) was found in a 71st Regiment manuscript book titled “Standing Regimental Orders in America”; the first half of the volume contains standing orders for 1775 (before the regiment arrived in North America), the second half entries for 1778, beginning 3 June and ending with a 24 August order. The context of the knapsack image is difficult to ascertain but, in my opinion, was likely done in 1778. A caveat – while we can assume it portrays a piece of British equipment, the possibility of the image showing a captured item remains in the realm of possibility. That possibility seems to be lessened by the absence of a descriptor noting such. Added to that, there are indications the British went into the war using single-pouch knapsacks, the 71st order book drawing, likely dating to 1778, being the earliest evidence for the double-pouch variety.

Next, a known item with a supposition attached to it. In February 1776 a contractor sent a proposal to convince the state of Maryland to procure for their troops his “new Invented Napsack and haversack.” In the end numbers of his knapsack were made and issued to several Maryland units, and probably some Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops. Though impossible to prove, an intriguing possibility is that the new British knapsacks were inspired by the American “Napsack and haversack,” a not unreasonable contention given the similarity in design and that the 71st knapsack drawing also shows one pouch designated to carry food.

From 1776, we move four years ahead, to Benjamin Warner’s service with Col. John Lamb’s 2d Continental Artillery Regiment. Given that his other tours, from 1775 to 1777, were with state or militia units, and given what we know of America knapsacks during those years, it is most likely his extant knapsack dates from his 1780 stint. Warner’s pack may have been copied from captured British equipment. The practice did occur, perhaps the best known instance being the Continental Army twenty-nine round “New Model” cartridge pouch, copied from British pouches taken with Burgoyne’s troops and first made in Massachusetts in the winter of 1777-78.

(See following page for images of the Warner knapsack.)

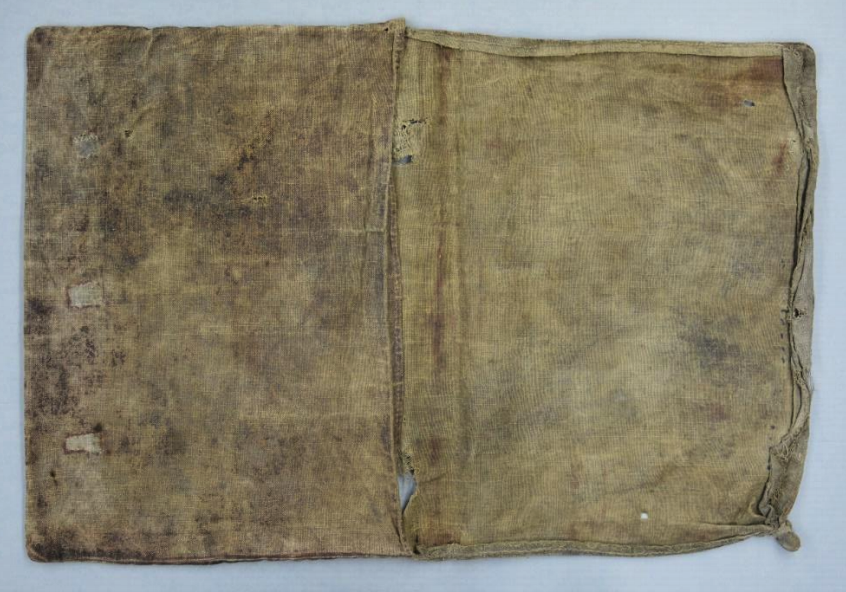

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack.

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack. While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

"I observe in your return the mention of upwards of three thousand yards of oznaburghs Tho' this kind of linen is not the best for knapsacks yet they have very commonly been made of it. Of that in your possession I wish you to select immediately the best, & to have one thousand knapsacks made up. They should be made double, & one side painted with the cheapest paints. I will furnish you with Mr. Morris's notes to enable you to pay for this work which cannot cost much. Be pleased to have the knapsacks made with dispatch & forwarded without delay to Colo. Hughes."

Numbered Record Books, National Archives, 1780-July 9, 1787, vol. 26.Timothy Pickering to Peter Anspach, 23 April 1782:

"Desire Mr. [Mery?] to examine the bolts of oznaburghs which came from Virginia, and pick out those fittest for knapsacks, & get as many made as he can: If he would cut out one of a proper shape, he could get some careful woman to cut out the residue, & employ other women to make them up. Let them be made double, & one side painted. Perhaps all the oznaburghs will answer as well as those knapsacks usually made. There are some here which were left or rather contracted for by Col. Mitchel, that are wretched indeed: I think any of our oznaburghs better by far."

Miscellaneous Numbered Records (The Manuscript File) in the War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records 1775–1790's, National Archives Microfilm Publication M859, (Washington, D.C., 1971), reel 87, item no. 25353.

Also in 1782, Pierre L’Enfant, captain Corps of Engineers, painted a panorama of West Point. To one side are two groups of Continental troops, including several soldiers wearing rolled blankets atop their knapsacks, the first images showing that being done.

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"]

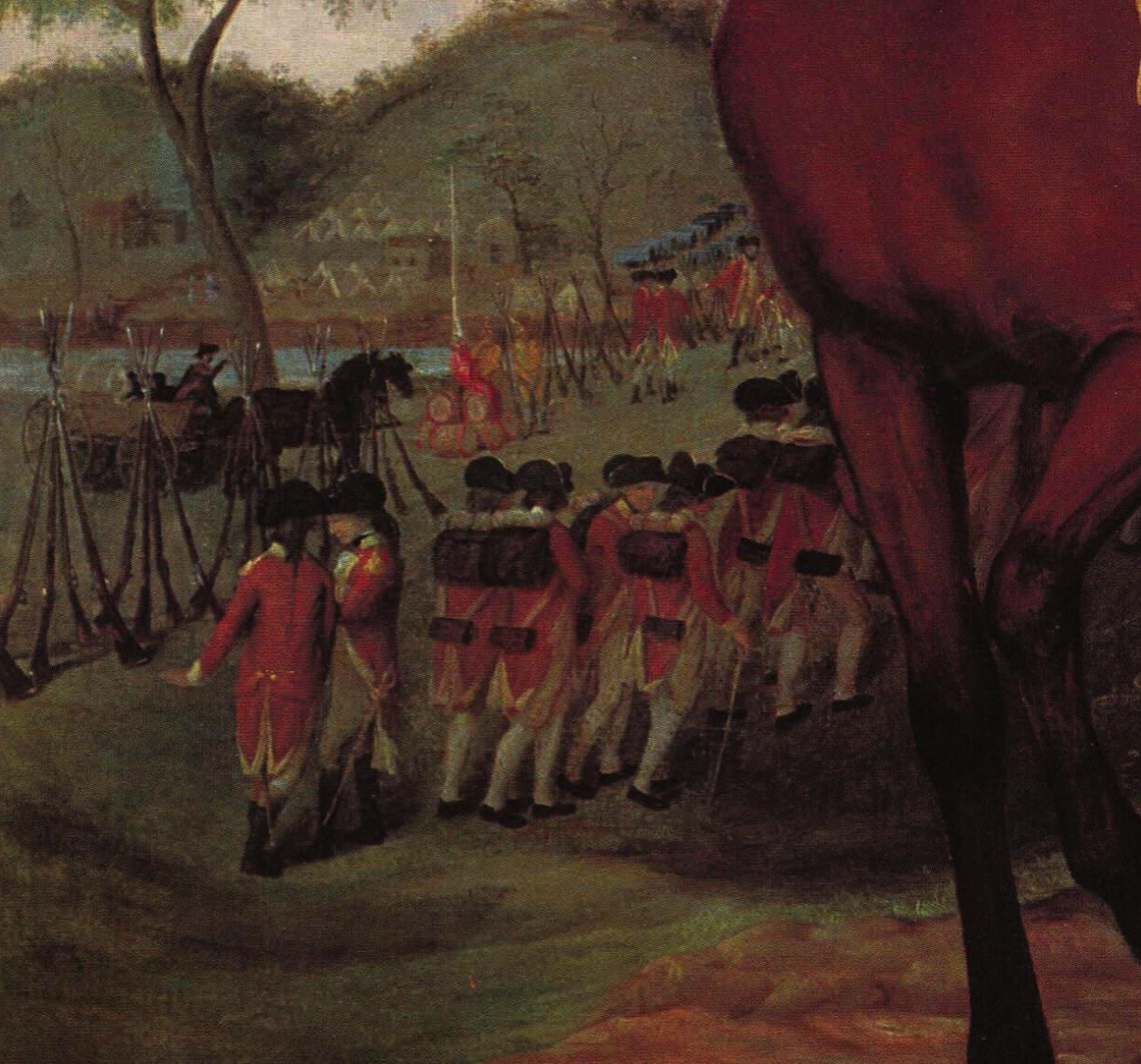

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"] Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .Read Part 1 of A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution Here !

A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution

“Square knapsacks are most convenient …”

This post began with the vague idea of discussing the 17th Regiment’s recreated knapsack. To my mind it is the only one that comes close to representing the design of the originals likely carried by mid-war (and possibly late-war) British soldiers. But that set me to ruminating on how the double-pouch knapsack (such as the Benjamin Warner pack at Fort Ticonderoga and the one pictured below in the 71st Regiment’s 1778 order book) came to be. The following narrative, based on both primary and, admittedly, circumstantial evidence, attempts to trace that transformation, and (spoiler alert) leads the author to think it very likely the double-pouch pack was a wartime innovation.

Drawing of knapsack from British 71st Regiment 1778 order book. This is likely evidence that double-bag knapsacks, undoubtedly of linen, were being used by British troops at least by 1778. Note that food was to be carried in one bag, and a minimum of necessaries (“1 pair of shoes,” “1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt, “1 Pr. stockings”) in the other. Continental Army twoshoulder-strap double-bag packs were probably copied from British knapsacks. The Warner knapsack (probably issued in 1779) had two storage pouches; orders for American army knapsacks in 1782 stipulated, “Let them be made double, & one side painted.” Standing Orders of the 71st Regiment, 1778, Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell, National Register of Archives for Scotland (NRAS 28 papers), Isle of Canna, Scotland, U.K.(Knapsack drawing courtesy of Alexander John Good.)51

[gallery ids="3610,3619" columns="2" link="file" size="full"]Recreated Knapsacks, 17th Regiment

There are occasions (actually, many occasions) when my understanding runs on a very slow burn. In this vein, researching and writing about knapsacks used before, during and after the American War (1775-1783), eventually led me to the conclusion that British knapsack design took a right turn early in that conflict. Is my conclusion conclusive? No, it isn’t, as there are missing pieces in the records, but the possibility (or probability) is intriguing.

* * * * * *In his 1768 treatise System for the Compleat Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry Bennett Cuthbertson wrote,

Square knapsacks are most convenient, for packing up the Soldier’s necessaries, and should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen: a certain size must be determined on for the whole, and it will have a pleasing effect upon a March, if care has been taken, to get them of all white goat-skins, with leather-slings well whitened, to hang over each shoulder; which method makes the carriage of the Knapsack much easier, than across the breast, and by no means so heating.9

Cuthbertson reveals here several notable clues. First, of course, is his statement touting the superiority of “square” knapsacks with two shoulder slings. The 1751 Morier figures and the circa 1765 painting “An Officer Giving Alms to a Sick Soldier” by Edward Penny (1714-1791) show soldiers wearing single-shoulder-strap skin packs, so Cuthbertson’s square knapsack was a relatively recent innovation. Mr. C. also states square packs “should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen” and “a certain size must be determined on for the whole …” ”[M]ade with a division.” That, to me, indicates Cuthbertson is speaking of a single pouch knapsack, like the David Uhl and Elisha Grose packs, while his remark about determining size can only mean no standard design had yet been settled on. And his reference to “all white goat-skins” refers to a knapsack likely made entirely of leather, again like the Grose knapsack. Both pre-war and in the war’s early years leather seems to have been the preferred material for many, perhaps most, knapsacks.

(For references to leather packs see sections titled “Leather and Hair Packs, and Ezra Tilden’s Narrative” and “The Rufus Lincoln and Elisha

Gross Hair Knapsacks” in “’Cost of a Knapsack complete …’: `This Napsack I carryd through the war of the Revolution,” Knapsacks Used by the Soldiers during the War for American Independence’” http://www.scribd.com/doc/210794759/%E2%80%9C-This-Napsack-I-carryd-through-the-war-of-theRevolution-Knapsacks-Used-by-the-Soldiers-during-the-War-for-American-Independence-Part-1-of-

%E2%80%9C-Cos ; see also, Al Saguto, “The Seventeenth Century Snapsack” (January 1989) http://www.scribd.com/doc/212328948/Al-Saguto-The-Seventeenth-Century-Snapsack-January-1989 )

[gallery ids="3628,3638" columns="2" size="full"]Detail from David Morier, “Grenadiers, 46th, 47th and 48th Regiments of Foot, 1751” http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection-search/david%2520morier

Based on the writing of Massachusetts militia colonel Timothy Pickering (below), sometime prior to 1774, packs like the one Cuthbertson described seem to have been adopted by at least some British regiments:

A knapsack may be contrived that a man may load and fire, in case of necessity, without throwing down his pack. Let the knapsack lay lengthways upon the back: from each side at the top let a strap come over the shoulders, go under the arms, and be fastened about half way down the knapsack. Secure these shoulder straps in their places by two other straps which are to go across and buckle before the middle of the breast. The mouth of the knapsack is at the top, and is covered by a flap made like the flap of saddlebags.- The outside of the knapsack should be fuller than the other which lies next to your back; and of course must be sewed in gathers at the bottom. Many of the knapsacks used in the army are, I believe, in this fashion, though made of some kind of skins.20

Pickering, too, refers to packs made of leather, infers that they had only a single pouch, and adds that the closing flap resembles those on saddle bags of the time. Period examples have closing flaps similar to those on the Uhl (linen) and Grose (bearskin) knapsacks.

So, just when were double-pouch knapsacks (like Benjamin Warner’s 1780 pack) first introduced to British troops in America? A drawing from a 1778 71st Regiment order book found and shared by Alexander John Good may provide the answer. That image shows a very simple double-pouch knapsack, with food placed in one pouch and “1 pair of shoes,” 1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt,” and “1 pr stockings” in the other. (It is interesting that this apportionment mirrors that of the “new Invented Napsack and haversack” used by some Whig units in 1776, 1778, and possibly 1777, but more on that later).

See the timeline of British Knapsacks at the bottom of this article.

British regiments already in America at the beginning of the war had knapsacks, but we have no idea of their design. At this time, given what we know of pre-war packs from period images and the comments of Cuthbertson and Pickering, I can only surmise that early-war (1775-1777) British knapsacks were leather (goatskin?), possibly linen, “square” models, with a single pouch (possibly with a divider to separate a spare pair of shoes from the other necessaries), and two shoulder straps. They also could not easily accommodate a blanket, an item deemed necessary for service in North America. British, French, and German troops campaigning in Europe did not carry blankets on the march, those coverings being carried in the same wagons as the regimental tentage. The packs (tournisters) German troops carried while serving in the American War still could not carry a blanket, and we are still unsure how, or even if, German troops carried blankets on the march.

Supply documents for the British Brigade of Guards, 1776 to 1778, including numbers of knapsacks issued and the use of blanket slings on campaign, and generate some interesting questions.

[Numbers of knapsacks needed and requested]

List of Waggons, Tents, Camp necessaries &ca for the Detachment from the Three Regiments of Foot Guards, consisting with their Officers of 1097 men destined to Serve in North America.

February 5th 1776 …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks(Loudoun p.213) (see also WO4/96 p.45 7 Feb. 1776 Barrington to Loudoun)[Knapsack pattern]Memo Brig. Gen. Edward Mathew to John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun 16 Feb. 1776 "Memorandum concerning the [Guards] Detachment Fryday Feb 16 1776" "Light Infantry Company. Colo. Mathews applies for the proper Clothing.proposes: To cut the 2nd Clothing of this Year into Jackets. --Caps, Colo. M to produce a pattern --Arms, The Ordnance will deliver them with the others. a fresh Application.Accoutrements, upon the plan of the light Infantry. Colo. M--Bill Hook and Bayonet in the same case. Colo M.-- ""Gaiters and Leggins Knapsack -- Genl. Tayler has a pattern. Nightcaps -- Colo. M to shew one Canteens -- to see a Wooden one."(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6510)[Altering knapsacks] Memo Mathew to Loudoun 28 Feb. 1776

"Estimate of the Extra expence of the Necessary Equipment of the Detachment from the Brigd. of Foot Guards Intended for Foreign Service"

Alteration of the Mens Knapsacks .6 [pence]To Receive from the Goverment in Lieu of Knapsacks 2.6Allowance from Govermt. to each Man for a Knapsack 2.6(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6514)[Fitting knapsacks] Regimental Order, London 7 March 1776The 1st Regt. will draught the 15 men "by Lot out of such Men as are in every respect fit for Service."2nd and 3rd Battalion to draught Sat the 9th 1st Battalion on Sun the 10thA return to be sent in of the name, age and service of the men. Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

"The Extraordinary necessaries furnish'd are not to be deliver'd to the Men till they are in their first Cantonments."

(First Guards)[List of soldiers’ necessaries, including knapsacks] Brigade Orders, London 13 March 1776"The Necessarys of the Detachment are to be Compleated to the following Articles -- Three ShirtsThree Pair worsted StockingsTwo pair of Socks 7/ 1/4 pr. PairTwo pair of ShoesThree pair of Heels and Soles 1/2 d pr. pairTwo Black StocksTwo Pair of Half Gaiters 1s/ pr. pairOne Cheque Shirt 3/9 dA Knapsack (2/6 d Allowed by Government)Picker, Worm & TurnscrewA Night Cap"(Scots)

A little over a month later, on 26 April 1776, the three Guards Battalions set sail for North America.

With all the trouble taken to procure knapsacks for the Guards Brigade, those packs seem to have either been left aboard the transports when the Guards went ashore at Long Island, New York or sent back on board after landing. Several 1776 documents mention knapsacks or the lack thereof during the New York campaign.

"[Guards] Brigade Orders August 19th [1776.]When the Brigade disembarks two Gils of Rum to be delivered for each mans Canteen which must be filled with Water, Each Man to disembark with a Blanket & Haversack in which he is to carry one Shirt one pair of Socks and Three Days Provisions a careful Man to be left on board each Ship to take care of the Knapsacks. The Articles of War to be read to the Men by an Officer of each Ship."(Thomas Glyn, "The Journal of Ensign Thomas Glyn, 1st Regiment of Foot Guards on theAmerican Service with the Brigade of Guards 1776-1777," 7. Transcription courtesy of Linnea M. Bass.)General (Army) Orders 20 August 1776"When the Troops land they are to carry nothing with them but their Arms, Ammunition, Blankets, & three Days provisions. The Commandg. Officers of Compys. will take particular care that the Canteens are properly fill'd with Rum & Water & it is most earnestly reecommended to the Men to be as saving as possible of their Grog." (1) (2)Brigade Orders 23 August 1776 [the day after their landing on Long Island]"the Brigade will Assemble with their Arms Accoutrements Blankets & Knapsacks to Morrow Morning at 5 oClock upon the same ground. . ." (2) (1)Brigade Orders 24 August 1776"the Commanding offrs of Battns may send their Knapsacks on board of Ships again if they find any ill Conveniency of them." (2) (1)It seems that many Crown soldiers used only slung blankets during the 1776 campaign, perhaps due to the “ill Conveniency” of their knapsacks, whatever that may mean. Here are two more 1776 references to carrying only blankets and blankets on slings:Orders, 4th Battalion Grenadiers (42nd and 71st Regiments), off Staten Island, 2 August 1776: "When the Men disembark they are to take nothing with them, but 3Shirts 2 prs of hose & their Leggings which are to be put up neatly in their packs, leaving their knapsacks & all their other necessaries on board ship which are carefully to be laid up by the Commanding Officers of Companys in the safest manner they can contrive."Capt. William Leslie, 17th Regiment of Foot, 2 September 1776, “"Bedford Long Island Sept.2nd 1776…

The Day after their Retreat we had orders to march to the ground we are now encamped upon, near the Village of Bedford: It is now a fortnight we have lain upon the ground wrapt in our Blankets, and thank God who supports us when we stand most in need, I have never enjoyed better health in my Life. My whole stock consists of two shirts 2 pr of shoes, 2 Handkerchiefs half of which I use, the other half I carry in my Blanket, like a Pedlar's Pack."61

Preparing for the 1777 campaign the British Guards were slated for another knapsack issue:Secretary at War William Barrington, 2nd Viscount Barrington to Loudoun 7 Sept 1776 His Majesty Orders that for the 1777 Campaign the Detachment is to receive the following CampNecessaries …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks10 Powder Bags(WO4/98 p. 144)Note: Correspondence on pages 150, 157, 171 indicates that only 150 knapsacks per regiment in America were supplied for the 1777 campaign. [That would make 450 total for three battalions.] And in March 1777 the following order was issued:[Guards] Brigade Orders 11 March 1777"The Waistbelts to Carry the Bayonet & to be wore across the Shoulder. The Captains are desired to provide Webbing for Carrying the Mens Blankets according to a pattern to be Seen at the Cantonment of Lt. Colo. Sr. J. Wrottesleys Company. The Serjeants to Observe how they are Sewed."(1) From an original manuscript entitled "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" which is actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day theBrigade for American Service was formed. Manuscript Dept., William L. Clements Library, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor. (Microfilm available for loan.)

So, were British knapsacks in use up to and including the year 1777 both single-pouch and incapable of accommodating a blanket? Were blanket slings used to carry blankets with knapsacks as well as without? Or were the knapsacks used by Crown forces at the time merely considered cumbersome, and blanket slings thought to be more proper for campaigning soldiers. Added to those questions, we are not at all certain how British soldiers carried their blankets even after double-pouch knapsacks came into use.

To Be Continued...

British Knapsack Timeline, 1758-17941758-1765 (and earlier), Single-pouch purse-like leather knapsack carried by British troops, as pictured in paintings by David Morier (1705-1770) and Edward Penny, R.A. (1714-1791). These knapsacks could not accommodate a blanket.1768, Cuthbertson recommends “square” knapsacks with two shoulder straps.1771, Painting of a private soldier of the 25th Regiment of Foot shows him wearing a hair pack with two shoulder straps. His knapsack seems to be a single-pouch model made of hide covered with hair, and, given the maud slung over his shoulder, could not accommodate a blanket.1774, Timothy Pickering describes a single-pouch, double-shoulder-strap leather knapsack being used in the British Army.1776, An American contractor touts his double-pouch, single-shoulder-strap linen “new InventedNapsack and haversack” to Maryland officials. One pouch was meant for food, the other for soldiers’ necessaries. Some Maryland units are known to have been issued the knapsack, and there is some indication it was used by Pennsylvania troops as well.1776-1777, British regiments are issued knapsacks, but many Crown units use blanket slings instead of packs in these two campaigns. (Possibly because the knapsacks then being used could not accommodate a blanket, which were deemed necessary for American service.)1778, The first known image of a double-pouch British knapsack appears in a 71st Regiment order book. One pouch is shown as holding food, the other, soldiers’ necessaries.1778, On 28 July “1096 Knap & Haversacks” (from the context likely the same as the “new Invented Napsack and haversack”) are sent from Reading, Pennsylvania to supply Continental troops.1780, Benjamin Warner was likely issued his double-pouch double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack while serving with a Continental artillery regiment. `1782, First known documentary references to double-pouch knapsacks.1782, L’Enfant painting of West Point showing soldiers with rolled blankets attached to the top of their knapsacks.1794, The earliest known surviving British double-pouch, double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack, made for the 97th Inverness Regiment, raised in 1794 and disbanded the same year.

Footnotes:

- H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, vol. I (Princeton, N.J., 1951), 154-155.

- 84th Regiment order book, Malcolm Fraser Papers, MG 23, K1,Vol 21, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Orderly Book: British Regiment Footguards, New York and New Jersey," a 1st Battalion

Order Book covering August 1776 to January 1777, Early American Orderly Books, 1748-1817, Collections of the New-York Historical Society (Microfilm Edition - Woodbridge, N.J.: Research Publications, Inc.: 1977), reel 3, document 37.

- Sheldon S. Cohen, "Captain William Leslie's 'Paths of Glory,’" New Jersey History, 108 (1990), 63.

- "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" (actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st

Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day the Brigade for American Service was formed), Manuscript Department, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.(Courtesy of Linnea Bass.)

- British Orderly Book [40th Regiment of Foot] April 20, 1777 to August 28, 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 6 (Military Papers, 1755-1798), vol. 1, reel 117. See also, John U. Rees, ed., "`Necessarys

… to be Properley Packd: & Slung in their Blanketts’: Selected Transcriptions 40th Regiment ofFoot Order Book,” http://revwar75.com/library/rees/40th.htm

- "Captured British Orderly Book [49th Regiment], 25 June 1777 to 10 September 1777, . George Washington Papers (microfilm), series 6, vol. 1, reel 117.

- "Orderly Book: First Battalion of Guards, British Army, New York" (covers all but a few days of 1779), Early American Orderly Books, N-YHS (microfilm), reel 6, document 77.

- R. Newsome, ed., "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781", North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX (January-October 1932), no. 2, 178-179; no. 3, 286, 287.

- Order book, 43rd Regiment of Foot (British), 23 May 1781 to 25 August 1781, British Museum, London, Mss. 42,449 (transcription by Gilbert V. Riddle).

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers' food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .

Three Captains of the 17th

Mark Odintz returns to the blog this week to reveal the stories of three key officers who served in the 17th during the American Revolution. Their experiences reveal the different paths that officers took in joining the regiment and the varieties of experiences that holders of the king's commission could expect to confront during their careers. As always, we appreciate Mark sharing his wealth of knowledge.

- Will Tatum

For my next installment of the officers of the 17th, I want to take a look at three long service captains of the regiment, Francis Tew, William Scott and William John Darby, men who spent most of their time in the service in the 17th. Darby and Tew’s ties to the regiment go back to the Seven Years War and all three were mainstays of the regiment for much of the American Revolution.

Francis Tew, one of the bravest and most stalwart (if also one of the unluckiest) officers of the 17th, was born in Ireland in 1737, the child of William Tew of Roddinstown, county Meath, and Hester McManus Tew of Maynooth. He came from the marginal edges of the landed gentry. His father was a third son, and had a large family. Francis’s eldest brother, Mark of Roddinstown, who inherited what property there was, attended Trinity College, Dublin and was described as a “farmer in County Meath”. (National Library of Ireland, Pedigree of Tew Family; plus notes on Tew family on Bomford.net).

Tew’s early career benefited from the expansion of the British army at the opening stages of the Seven Years War. He entered the 17th as an ensign, most likely without purchase, on April 27, 1756, and was promoted to lieutenant, also without purchase, on Feb. 2, 1757. He served in the grenadier company at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758, and was caught up in one of the few setbacks suffered by British arms during that well-conducted siege. On the night of July 9th the French garrison sortied against the post held by the grenadier company of the 17th and achieved a complete surprise. The company commander, Captain William, Earl of Dundonald, was killed, and Lieutenant Tew was wounded and captured. According to his own memorial of 1770 he “recd 7 Musket Balls in different parts of his body” and his wounds are described in more excruciating detail in Roger Lambs “Journal of the American War”. According to Lamb his wounds appeared so serious that he was not treated for three days, “the surgeons expecting his death every half hour.” He eventually recovered, and rejoined the regiment for the West Indian campaigns at Martinique and Havana. (Lamb, p. 274-75; Barrington Papers, 6D/379, memorial of Francis Tew, 1770 or 1771).

In a rather striking example of how officers without money to purchase could endure wounds and long service and still be stuck in the junior ranks of the officer corps, Tew was still a lieutenant when the regiment returned to England at the end of the war. When the 17th was reviewed at Kew in 1768 General Lord Amherst paid particular attention to Tew “on account of his great sufferings at Louisbourgh”, and, if Lamb’s account is to be believed, the King noticed him as well “and after conversing with him very familiarly for some time, put his name down in his memorandum book, in order that he might not forget him when an occasion for promoting him should occur.” (Lamb, p. 275; WO 34: 157, f. 190, Memorial of Rose, Eleanor, and Hester Tew, Oct 12, 1779) Whoever talked to him at the review, Francis had to wait two more years before purchasing “with difficulty” the captain lieutenantcy of the 17th on Aug. 6, 1770. He was promoted to captain without purchase on the death of Captain Hope on Nov. 14, 1771.

Tew came back to America with the 17th to fight in the Revolution, and as the most senior captain was frequently in command of the regiment while it was in the field. At Princeton the lieutenant colonel, Charles Mawhood, was detached as commander of the entire British force and the major, Turner Straubenzee, was off commanding a battalion of light infantry. The following year, at Germantown, both field officers were absent once again, and Tew led the regiment through that battle as well. His final action was at Stony Point in 1779. On the night of the surprise attack Captain Tew, acting commander of the regiment (since Lt. Col. Johnston was in command of the entire garrison) was stationed at one of the forward posts. According to the account of Lieutenant John Ross, while attempting to rally his men Tew was confronted by “a body of rebels…who desired them to surrender on which Captain Tew made use of some hasty expression, which the witness does not remember but Capt Tew was immediately fired on and killed.”. It seems fitting that the old soldier was shot down while raging at the enemy. Roger Lamb eulogized him in his history of the war, saying that “his loss was at the time sensibly felt through the army.” (WO71:93, Court martial of Henry Johnson; Lamb p. 274).

There is no evidence that Francis Tew ever married. In October of 1779 and April of 1780 Rose, Eleanor and Hester Tew, the spinster sisters of Francis, sent a series of memorials to government figures petitioning for relief, “our former distresses having been grievously augmented by the loss of our most kind and lamented brother.” They were placed on the compassionate list, at 10 pounds a year each. (WO34:157, F. 190, Rose, Eleanor and Hester Tew to Amherst, Oct. 12, 1779; WO1:1006, f. 681, Same to Jenkinson, April 7, 1780; WO34:161, f. 534, Jenkinson to Amherst, Mar. 30, 1780).

Our next officer, William Scott, like Tew and Brereton, particularly distinguished himself during the American Revolution. Like Tew he also seems to have come from the edges of middle class society, though there was evidently ample funding for his military career. His father Benjamin Scott of Osborn near Cranbrook, Kent, was deputy collector of the custom house at the port of London, working under Edward Louisa Mann of the influential Mann family of Linton. William Scott was born c. 1752 and entered the 17th as an ensign by purchase on Jan. 15, 1770. With funds in hand he was able to take advantage of the fact that a number of veterans of the Seven Years War wanted to retire in the 1770s, purchasing his lieutenantcy on Sept. 23, 1772 and his captaincy on August 23, 1775. He purchased his company from Richard Aylmer, who, as his family later complained, had “purchased all his commissions at a very dear rate, so much so, that his company cost him 2000 guineas.” (WO25:3090, memorial of Eliza Aylmer, 10 March 1821.) Most likely Scott was forced to match that sum.

Scott served as a company commander during the early years of the Revolution, first as captain of a line company, then as captain of the light infantry company. At the battle of Princeton in January of 1777 Scott particularly distinguished himself. According to the diary of Thomas Sullivan of the 49th Foot: “Captain Scott of the 17th Regiment with a party of 40 men under his command, having the Guard of the 4th Brigade’s Baggage, was attacked by a large body of the Enemy that were retreating from Princetown; but he formed his men upon commanding ground, and after refusing to deliver the Baggage, fought with his men back to back; and forced the Enemy to withdraw, bringing off the Baggage safe to Brunswick.” General Howe, while commending the role played by the 17th as a whole in the battle, particularly singled out Scott

“for his remarkable good conduct in protecting and securing the Baggage of the 4th Brigade…”

A few months late he replaced William John Darby as captain of the light infantry company, and commanded it during the Philadelphia campaign. He is believed to have been the author of one of the most detailed and vivid accounts of light infantry tactics to survive from the war. At the battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, Scott led his company in an attack on Birmingham Meetinghouse and several enemy cannons firing on them from a nearby hill. “The church yard wall being opposite the 17th light company, the captain determined to get over the fence and into the road; and calling to the men to follow…and lodged the men without loss at the foot of the hill on which the guns were firing.” The detailed account then goes on to describe the company using fire, movement and shock as an independent unit, and, more strikingly, cooperating with other individual companies from the light infantry battalion and even calling on the assistance of a neighboring company of grenadiers from a different battalion. This is far from the stereotype of inflexible battalions maneuvering about the battlefield, and demonstrates the level of leadership and tactical judgement required of light infantry captains like Scott. (See Matthew Spring, “With Zeal and with Bayonets Only”, pp. 185-187).