In our previous installment of this series, I discussed how stumbling across Chelsea Pension documents for soldiers of the 17th who had served in America began the research that led to the initial recreated unit. Having identified named individuals, the next logical step was to visit the muster roll data contained in the WO 12 series, also housed at The National Archives (UK).

In conducting research on practically any topic, the most profitable means of proceeding is usually to follow the money trail. One of History’s great constants is that fiscal specie talks and everyone, particularly government agencies, are keen to keep track of it. This golden rule was especially true for the eighteenth-century British Army. Always a controversial arm of the state, the army and the government ministers who labored to keep it standing throughout the century had to defend against two popular avenues of political assault: that the army cost too much and that it constituted a threat to English liberty. To justify the price tag associated with maintaining thousands of soldiers on duty during peace time, the civilian government developed a variety of paperwork-heavy procedures, for which historians should be quite thankful today.

Mustering was chief among these financial protocols. With origins stretching back to the Middle Ages, mustering had developed into a highly-developed ceremony of bureaucracy by the 1770s. Twice per year, muster-masters or deputy muster-masters would visit each regiment, which would form up on the muster field. At that time, the muster master or his deputy would roam through the ranks, paperwork in hand, insuring that each company had exactly the number of men in it that the officers claimed and would record the names of each man. If a man supposedly in the company was absent from the muster field, regulations required that the officers provide convincing proof that the soldier was either ill or “on command”—that is, on a detached duty. Contemporary critics claimed that the whole spectacle was rife with corruption: for a good account, check out John Railton’s The Army Regulator, which you can also find on ECCO (Eighteenth Century Collections Online) and potentially on googlebooks.

Despite being a procedure that was a pain to carry out even in peace time (especially in America), regiments prepared musters twice a year, every year, through the American Revolution. Sometimes, due to the exigencies of active campaigning, these muster rolls were prepped many months past their formal date (sometimes years later), but with that said, these are the foremost documents for understanding who was in a particular British regiment and how internal personnel management changed over time. A complete set for the 17th exists at the National Archives in Kew, England, reaching all the way back into the 1760s. When I pulled up the first set of musters covering 1776, I was slightly surprised.

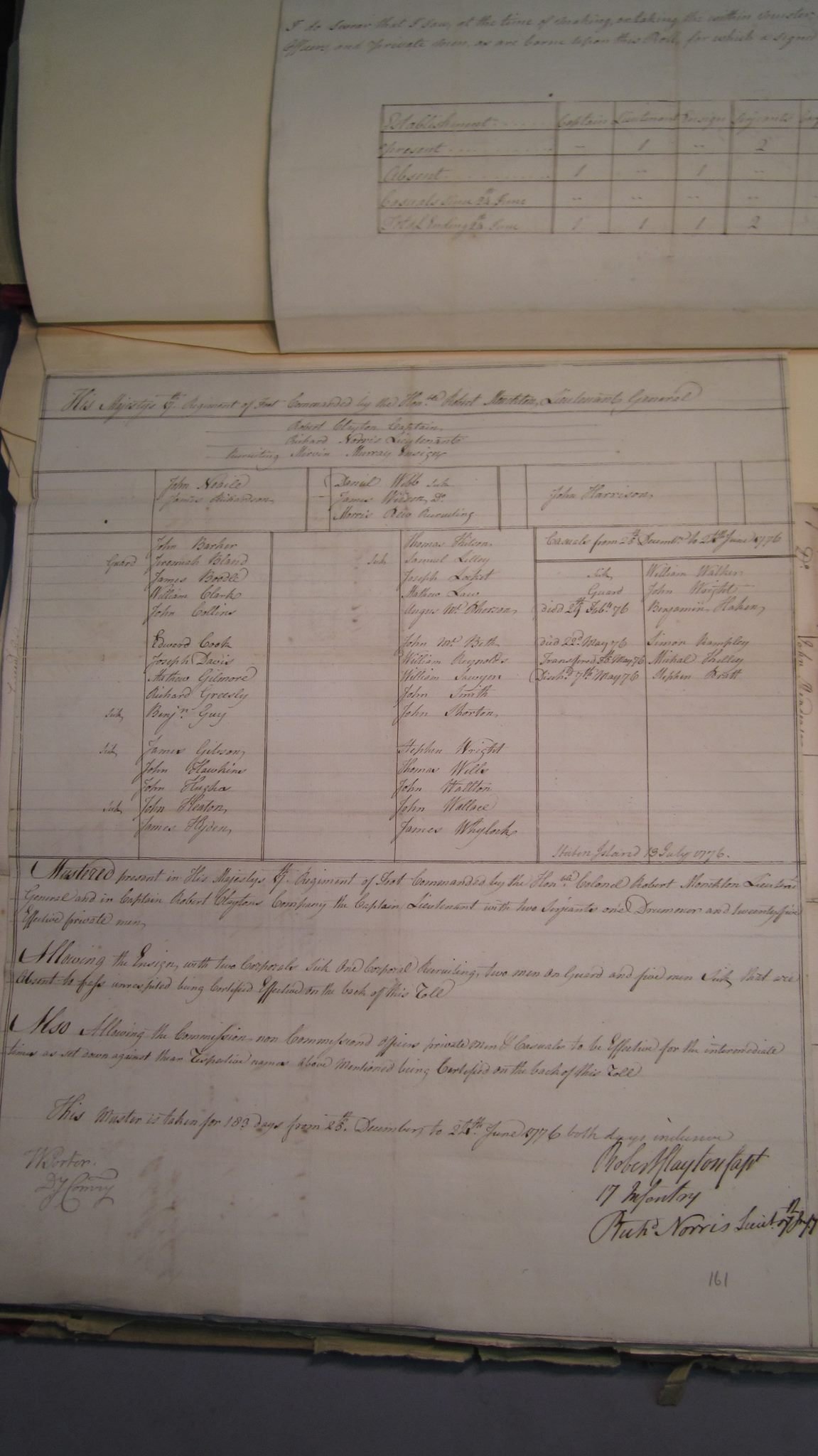

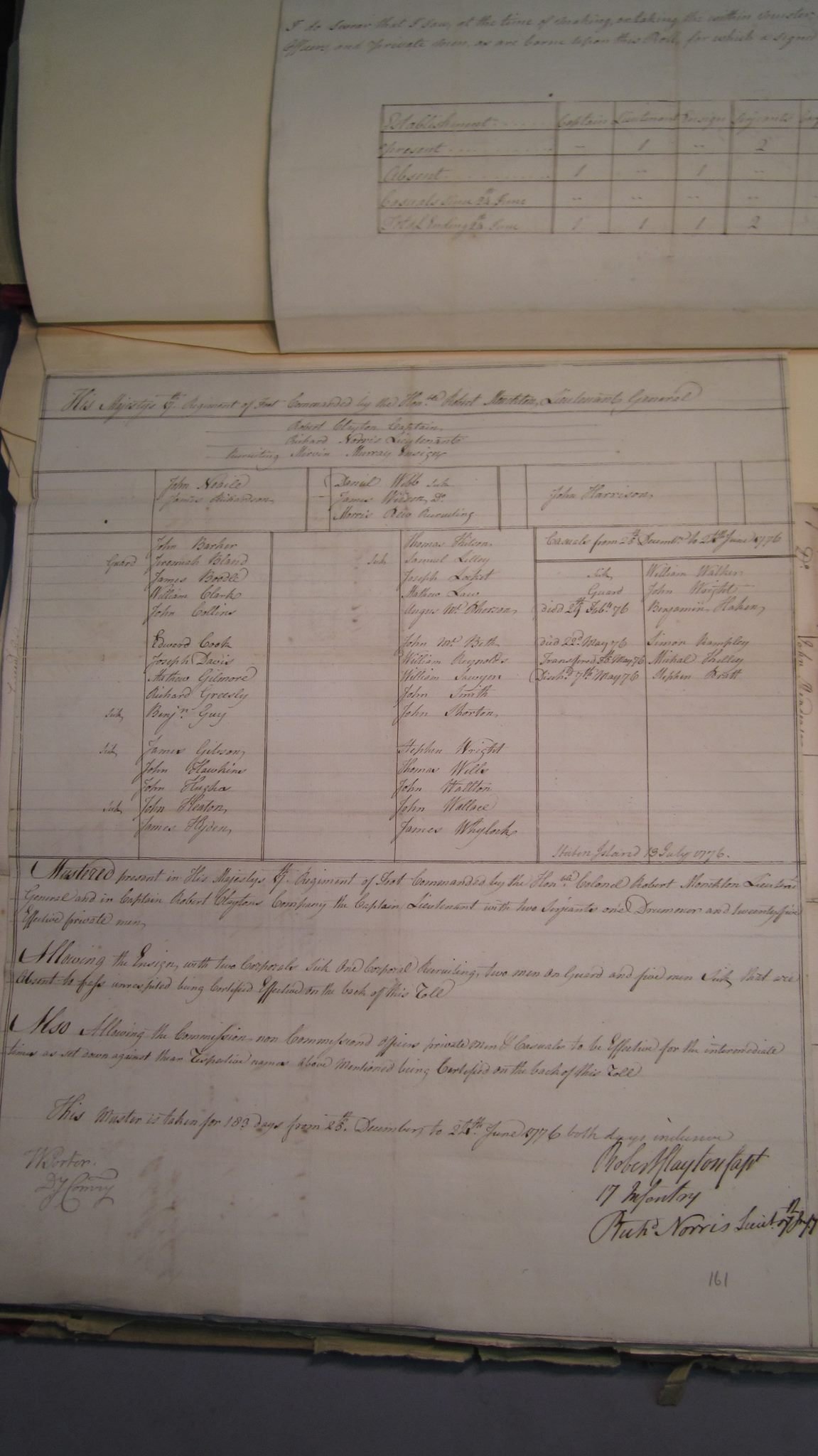

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Bear in mind that in 2002, your average digital camera was the size of a small current-production desktop printer. And I did not have one on me. We won’t even discuss the image quality that available units offered at that time (low single-digit megapixels…). So while I was overjoyed to see sheet after sheet like the above. I was also dumbfounded. How was I supposed to record this information and use it in a meaningful way? What was a meaningful way to use this information for living history? So, as in many other pickle-y research situations that year, I emailed Don Hagist for advice. Having been in my shoes before (decades before), Don advised that I move through as many muster rolls as possible, recording officers’ names and noting the inevitable changes in command that happened when men died or found promotion in other regiments. He also recommended that I note which officers remained in the regiment for the entirety of the war, which would provide a strong foundational name for the recreated unit.

There was only one. His name was Robert Clayton and he had risen to command the junior company of the 17th on May 1, 1775, at the age of 27 with 7.5 years of service. He was commissioned as an ensign on December 9, 1767, then promoted to lieutenant on July 19, 1771. He remained a captain for the entire war, eventually achieving the rank of major on July 27, 1785. I focused on recording relevant information for his company, then ended up transcribing information from all of the 17th muster rolls covering 1776, having in mind that the initial focus of the impression would be the 17th as it appeared on January 3, 1777, at Princeton, New Jersey. Over subsequent years, I returned with a succession of digital cameras to photograph all of the 17th’s muster rolls. Some interesting stories came out of these documents…but that is a tale for another time.

Will Tatumreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Over the subsequent years, he has traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain researching the eighteenth-century British Army and used the results of those labor to improve living history interpretations. The beginning of this journey in 2001 marked the start of the current recreated 17th Infantry.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.