There are several guides to washing laundry in the 18th century—some are quite detailed, while others are fantastically vague (“enough indigo to make the water sky blue”). What follows is a quick compilation of several of those guides, various civilian and military notations about laundering in the American colonies, plus a few personal observations.

Laundering an article of clothing was often done through the same process as finishing a newly-woven textile. The process usually began with a soaking of some sort. One method of soaking was to use a hot or cold lye. This soaking process was usually referred to as “bucking,” and some households had a specific bucking tub or basket. Bucking served to break down grease, loosen dirt, and whiten yellowed linen. The items to be laundered were placed in the bottom of the tub, and a piece of cheesecloth was placed over the top of the tub. Ashes were then placed on top of the cloth, and hot water was poured atop the ashes. The lye was collected, then reheated, and poured through again. Chamber lye was also used for bucking—as well as for removing lanolin from wool and setting dyes. Hannah Woolley notes in The Complete Servant Maid (1677): “Before that you suffer it [linen cloth] to be washed, lay it all night in urine, the next day rub all the spots in the urine as if you were washing in water; then lay it in more urine another night and then rub it again, and so do till you find they [ink stains] be quite out.” [1] As this is an extended process, it’s not always a part of the wash cycle, but a part of what Hannah Glasse refers to as a “great wash.”[2]

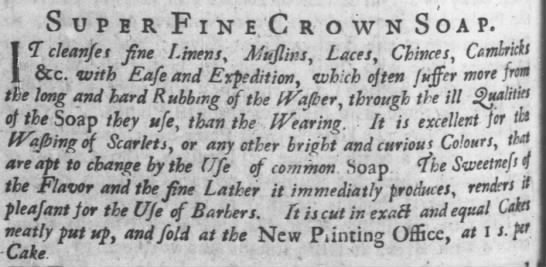

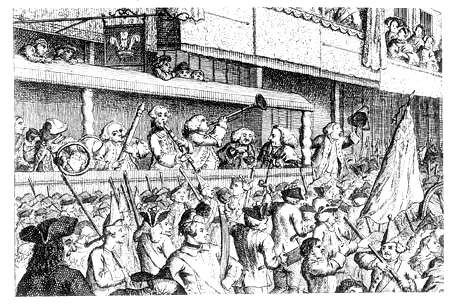

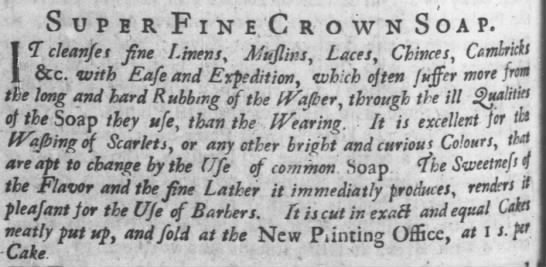

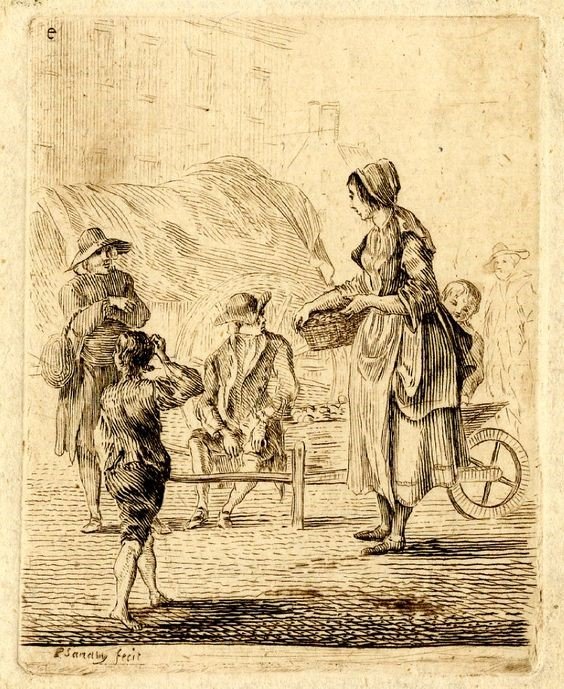

Once the soaking process was complete, soap was then applied to dirty spots and rubbed between the hands. There is absolutely no evidence of rub boards, scrub sticks, or washboards in inventories, instructions, or images. Experimental archaeology has shown two things: rubbing the item between the hands with soap or scrubbing the item along the inside of the bucking tub removes dirt and stains fairly well. Occasionally, a laundress will be instructed to use a brush to work in a stain remover such as lemon juice or vinegar, but that appears to be referencing stains on woolens, fine linens, cottons, or silk. Laundry bats and possers may also be used to squeeze water and soap (sometimes not soap) through clothing in order to clean it. In some locations, laundry would have been trampled with the laundress’s feet, as shown in the famous (infamous) image of the Scots washerwoman. A letter from Edward Burt, an Englishman traveling in northern Scotland in 1754 observed:

“... commonly to be seen by the sides of the river ... in all the parts of Scotland where I have been ...women with their coats [petticoats] tucked up, stamping, in tubs, upon linen by way of washing ….” [3]

Occasionally, laundry was boiled BEFORE soaping, as John Harrower described to his wife:

“They wash here the whitest that I have ever seed for they first Boyle all the Cloaths with soap, and then wash them, and I may put on clean linen every day if I please….” [4]

Most sources, however, note that hot water sets the stains and the clothes should be boiled after rubbing. Janet Schaw, an Englishwoman, observed laundry being done in Wilmington, NC in 1776. She wrote that

“all the cloaths coarse and fine, bed and table linen, lawns, cambricks and muslins, chints, checks, all are promiscuously thrown into a copper with a quantity of water and a large piece of soap. This is set a boiling, while a Negro wench turns them over with a stick.” [5]

From this, we can infer that most laundry would have been separated before boiling.

Schaw also had much to say about the rest of the laundry process:

This operation [boiling] over, they are taken out, squeezed, and thrown over the Pales to dry. They use no calendar; they are however much better smoothed when washed. Mrs Miller showed them [how to wash linen] by bleaching those of Miss Rutherfurd, my brother and mine, how different a little labour made them appear, and indeed the power of the sun was extremely apparent in the immediate recovery of some bed and table-linen, that has been so ruined by sea-water that I thought them irrecoverably lost. [6]

Schaw also noted that North Carolinians were the “worst washers of linen I ever saw, and tho’ it be the country of indigo, they never use blue, nor allow the sun to look at them.” [7] Indigo was used as a bluing agent— an optic brightener—and was added to the final rinse. It is unclear as to how much indigo was actually used; a few guidebooks note that enough indigo should be added to “make the water sky-blue.” Most bluing references in America are to fig blue or fig indigo, was probably a lesser grade of indigo. As indigo was a cash crop of Carolina, it was readily available in the American colonies. Stone blue is another term seen on occasion.

Blue could be added to starch, as noted in Amelia Chambers’s The Ladies’ Best Companion:

Moisten the quantity of starch you want to use, according to the quantity of your cloaths, with water, and put as much stone blue as is necessary. When the starch and blue are properly mixed, then let the whole boil together a quarter of an hour longer, taking care to keep stirring it, because that makes it much stiffer and is better for the linen. Such things as you would have most stiff, ought to be put first into the water, and you may weaken the starch by pouring a little water upon it. Starch ought to be boiled in a copper vessel, because it requires much boiling, and tin is apt to make it burn. Some people mix their starch with allom, or gum arabic, nothing is so good as isinglass, and an ounce of it is sufficient to a quarter of the pound. [8]

Starch receipts from the period used a variety of items: potatoes, rice, wheat, even horse chestnuts (patented in 1796 to Lord William Murray).

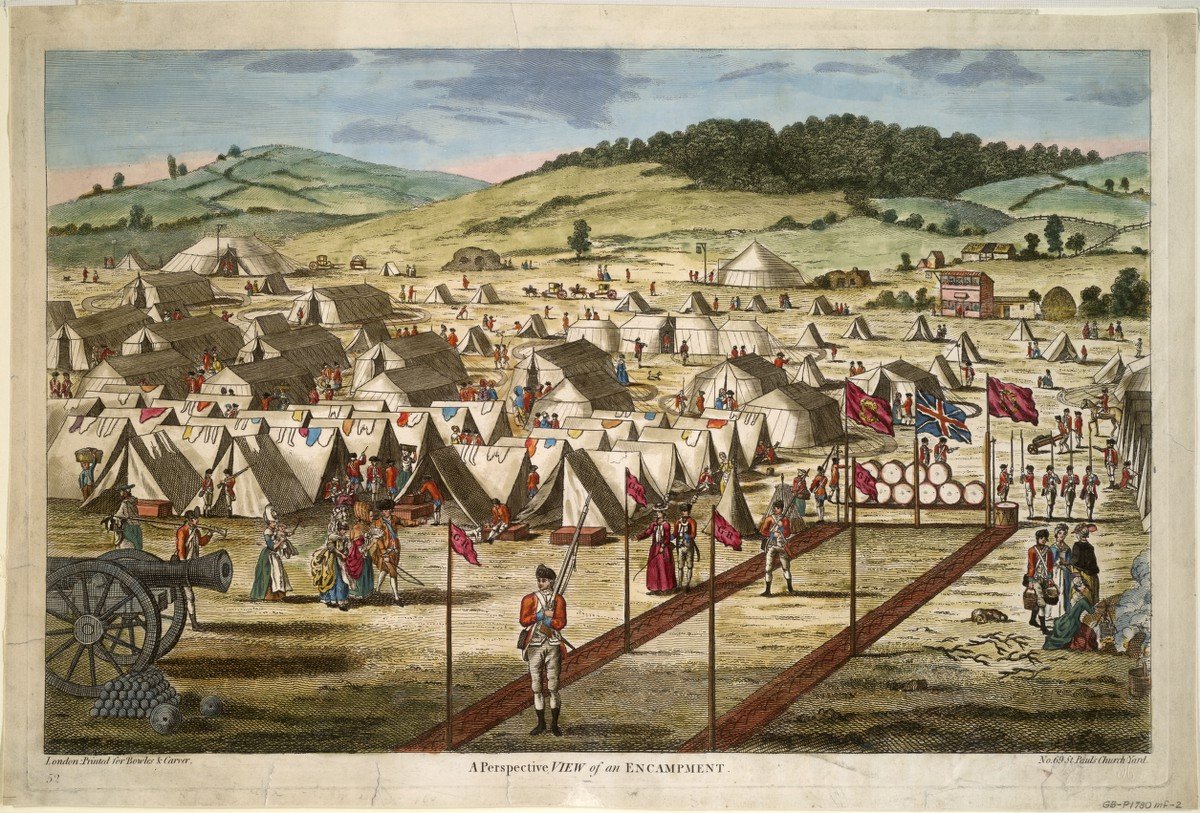

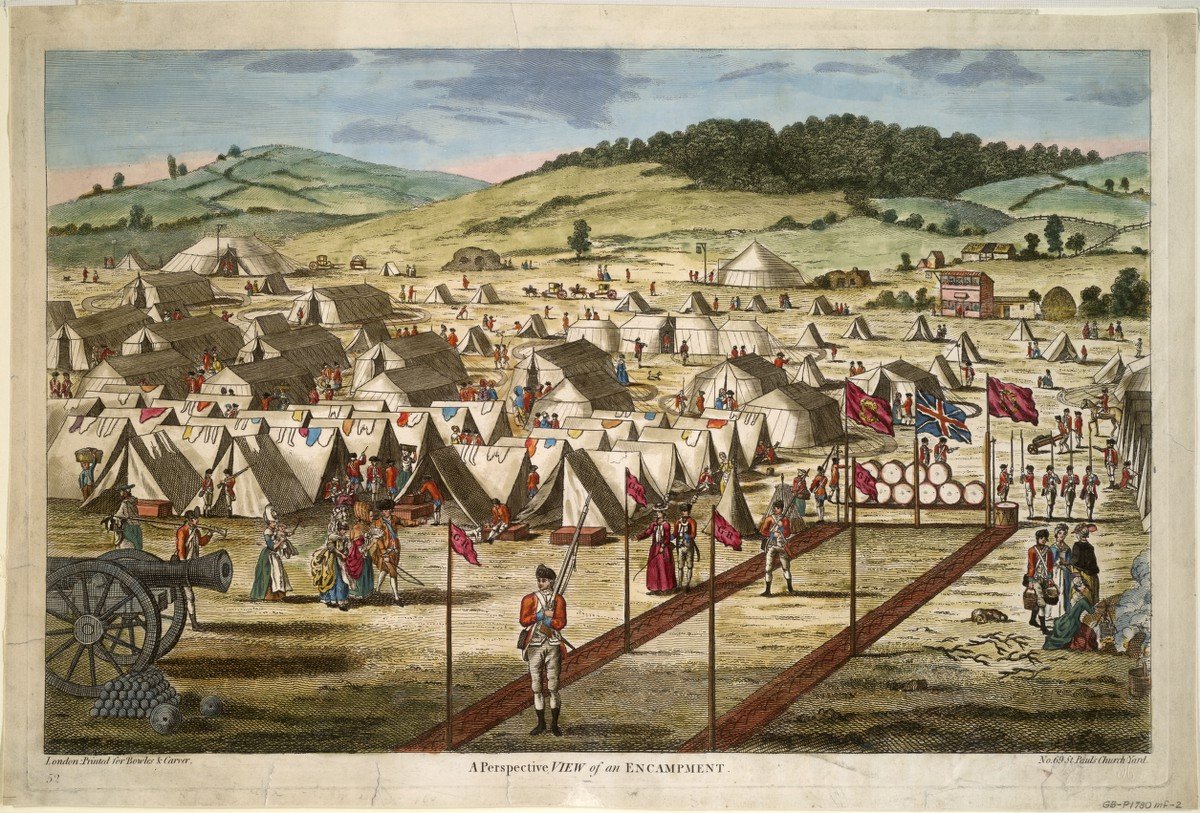

Once the rinsing and bluing was complete, the laundry was then dried. Period images show laundresses drying laundry in any open space: on wash-lines (usually made from linen or hemp rope), across tents, hung on fences and bushes, and even laid out in the grass. The sun acted as a bleaching agent. (See above for Ms. Schaw’s comment on the sun.) Once the laundry was dry, the laundress then faced the task of ironing or smoothing the linen. Those items that needed ironing needed to be re-dampened and then were placed on a table with a cloth above and beneath (there are a few images of camp laundry being smoothed on the ground). Then a wooden roller or heated iron was passed over the damp linen, stretching and smoothing the article of clothing.

There appears to have been much variation in the quality of the washing done in America. While linen was the predominant fabric being washed, laundresses were also tasked with cleaning dyed and/or printed linens and cottons, woolens, and silk. These materials could, indeed, be cleaned, but often required much more time and effort in their care. As such, outer garment were not washed as often as undergarments, but they were most definitely cleaned.

Footnotes:

[1] Hannah Woolley, The compleat servant-maid; or, The young maidens tutor Directing them how they may fit, and qualifie themselves for any of these employments. Viz. Waiting woman, house-keeper, chamber-maid, cook-maid, under cook-maid, nursery-maid, dairy-maid, laundry-maid, house-maid, scullery-maid. Composed for the great benefit and advantage of all young maidens. (London: printed for T. Passinger, at the Three Bibles on London Bridge, 1677), 69. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A66839.0001.001/1:7?rgn=div1;view=toc[2] Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy: Which Far Exceeds Any Thing of the Kind Yet Published, (London: W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton, et al, 1774), 330.[3] Edward Burt, Letters from a gentleman in the North of Scotland to his friend in London ... likewise an account of the Highlands with the customs and manners of the Highlanders, (London: Ogle, 1822).[4] John Harrower, “Diary of John Harrower, 1773-1776,” American Historical Review 6, no. 1 (1900), 84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1834690.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A67f1d3a92c1ae1a426a54ea7c55502c0[5] Janet Schaw, Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776, eds, Evangeline Walker Andrews and Charles McLean Andrews, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 204.[6] Ibid., 206.[7] Ibid., 206.[8] Amelia Chambers, The ladies best companion; or, a golden treasure for the fair sex. Containing the whole arts of cookery ... With plain instructions for making English wines ... To which is added The art of preserving beauty, London: Printed for J. Cooke, 1800.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

Her research areas include Germanic settlement and culture in the greater Shenandoah Valley, the material culture of followers of the British Army through the American Revolution, and the Women’s Land Army of America in Virginia and North Carolina during the first World War. She is a founding member of the progressive civilian organization, The Laundry Company. She loves cats, coffee, and puns, and not necessarily in that order.

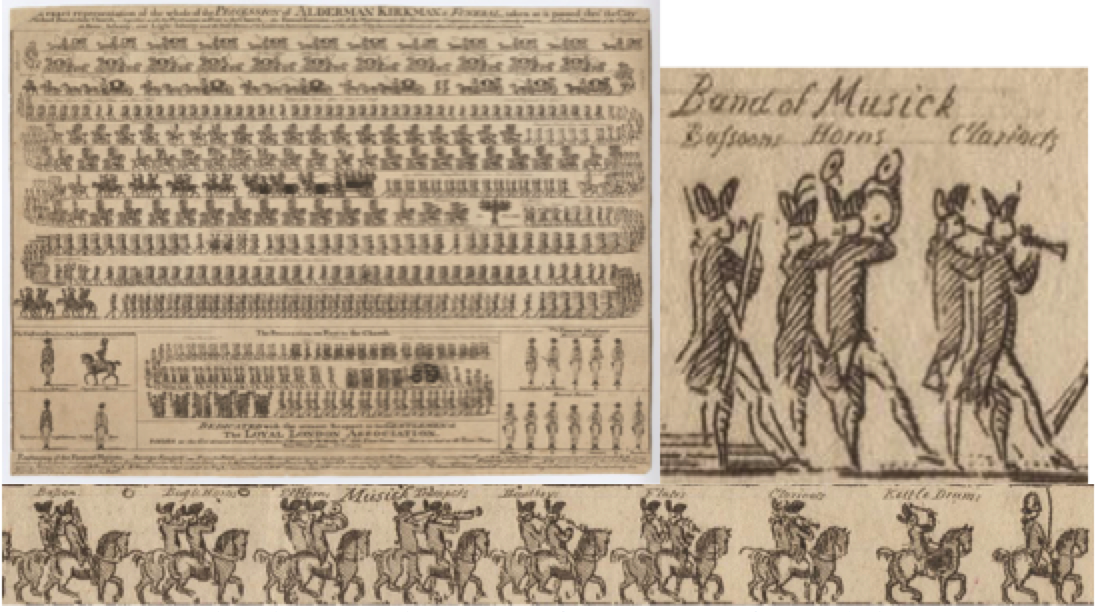

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

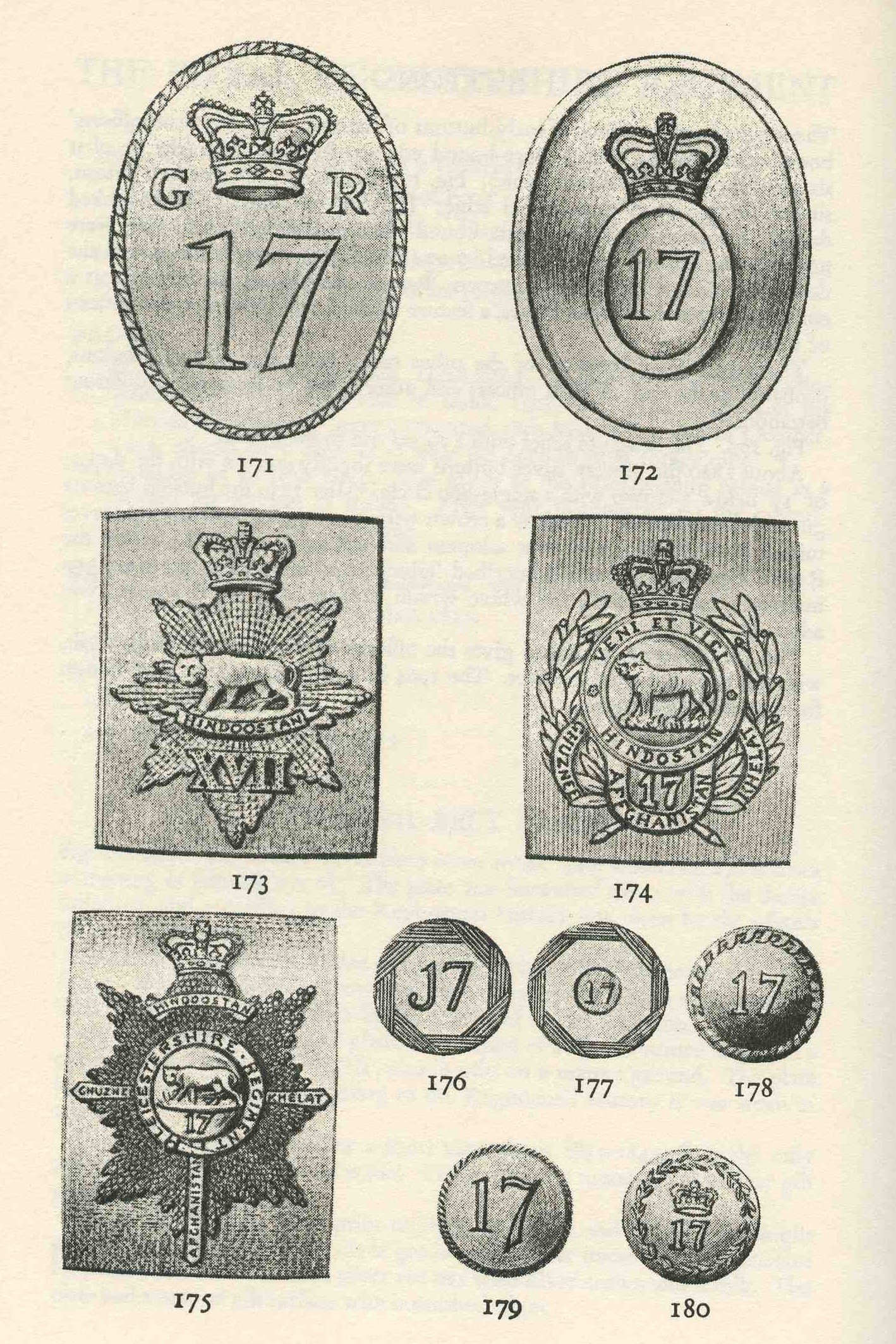

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

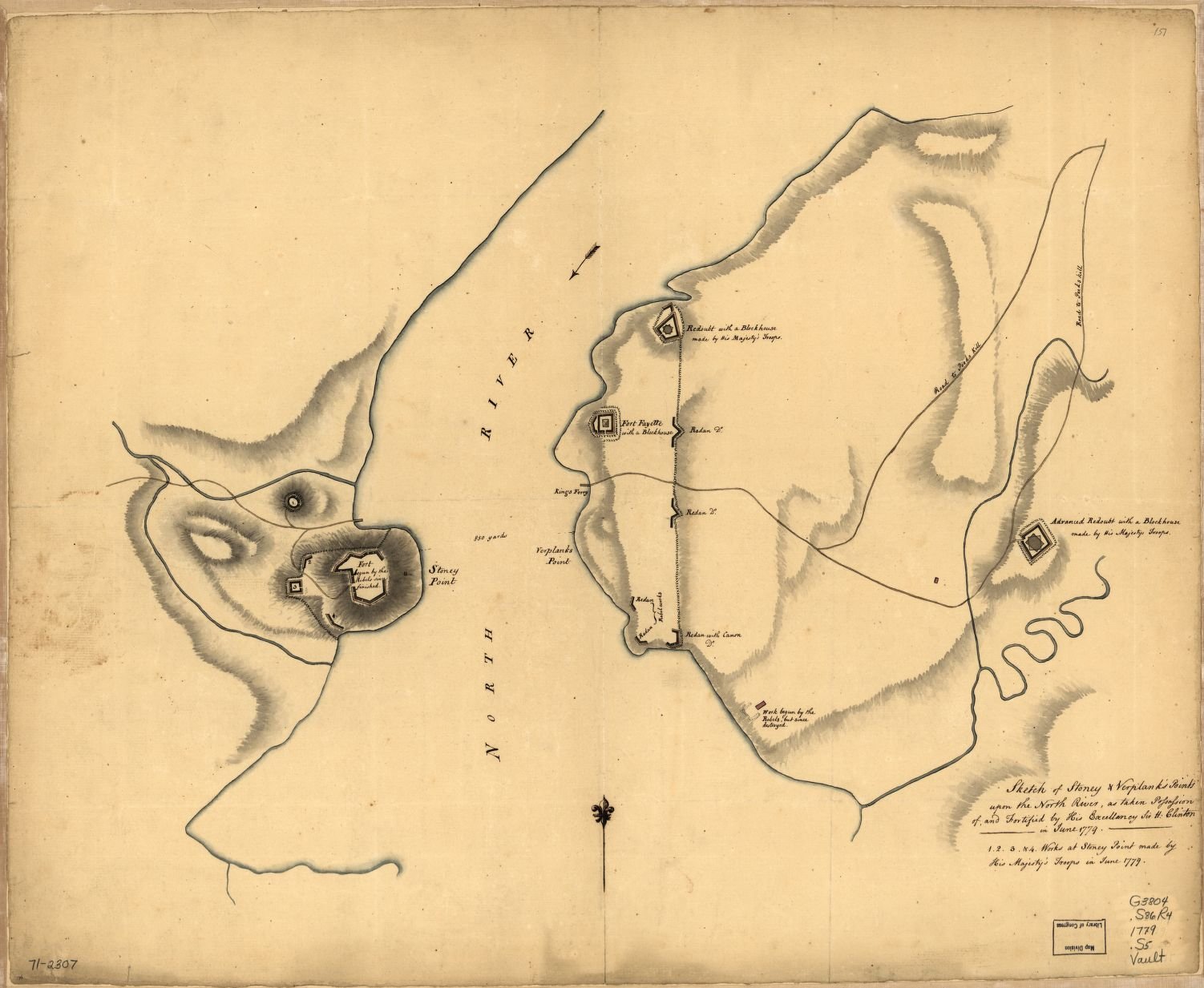

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of

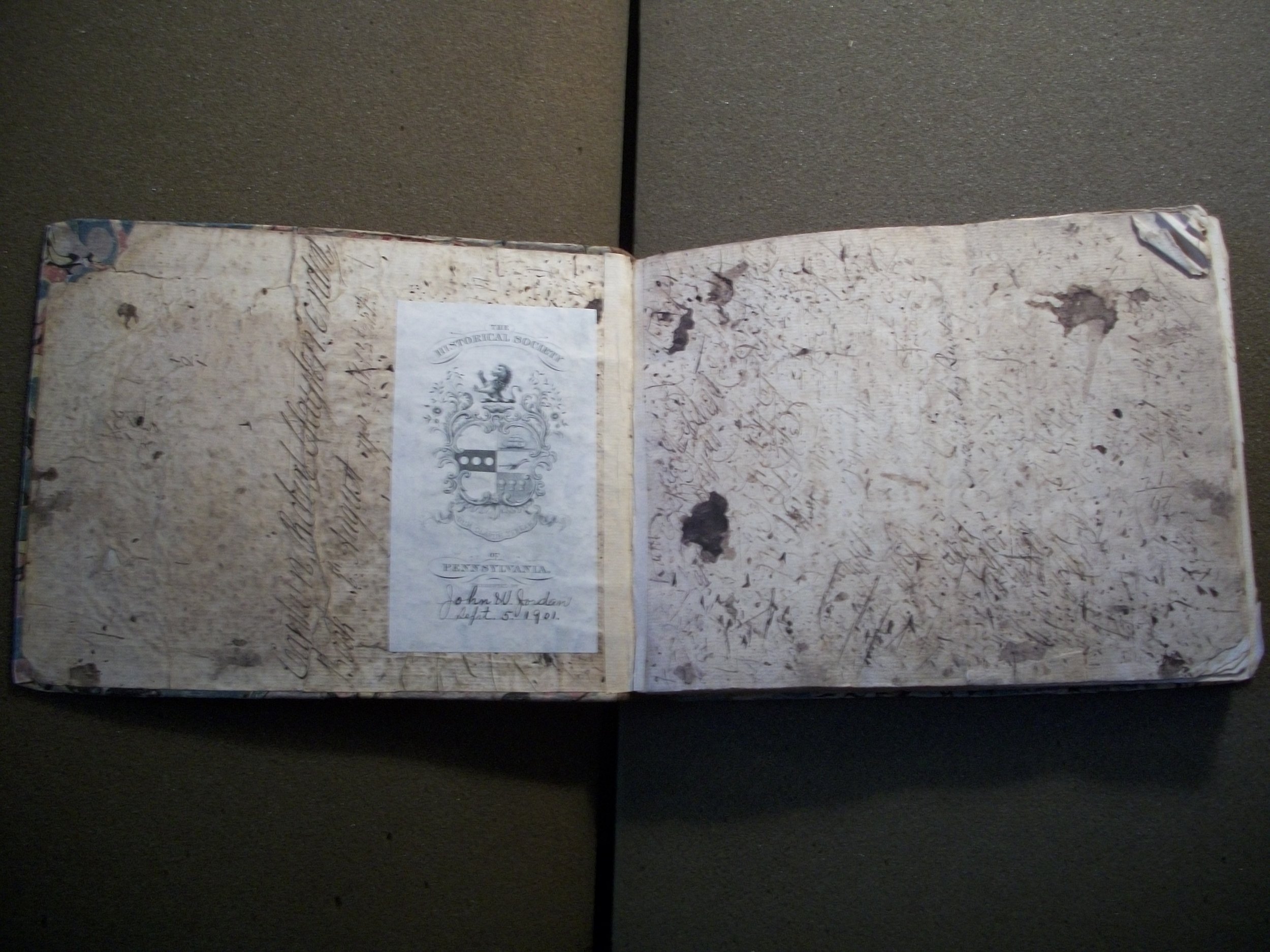

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of  Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Dr. Mark Odintz

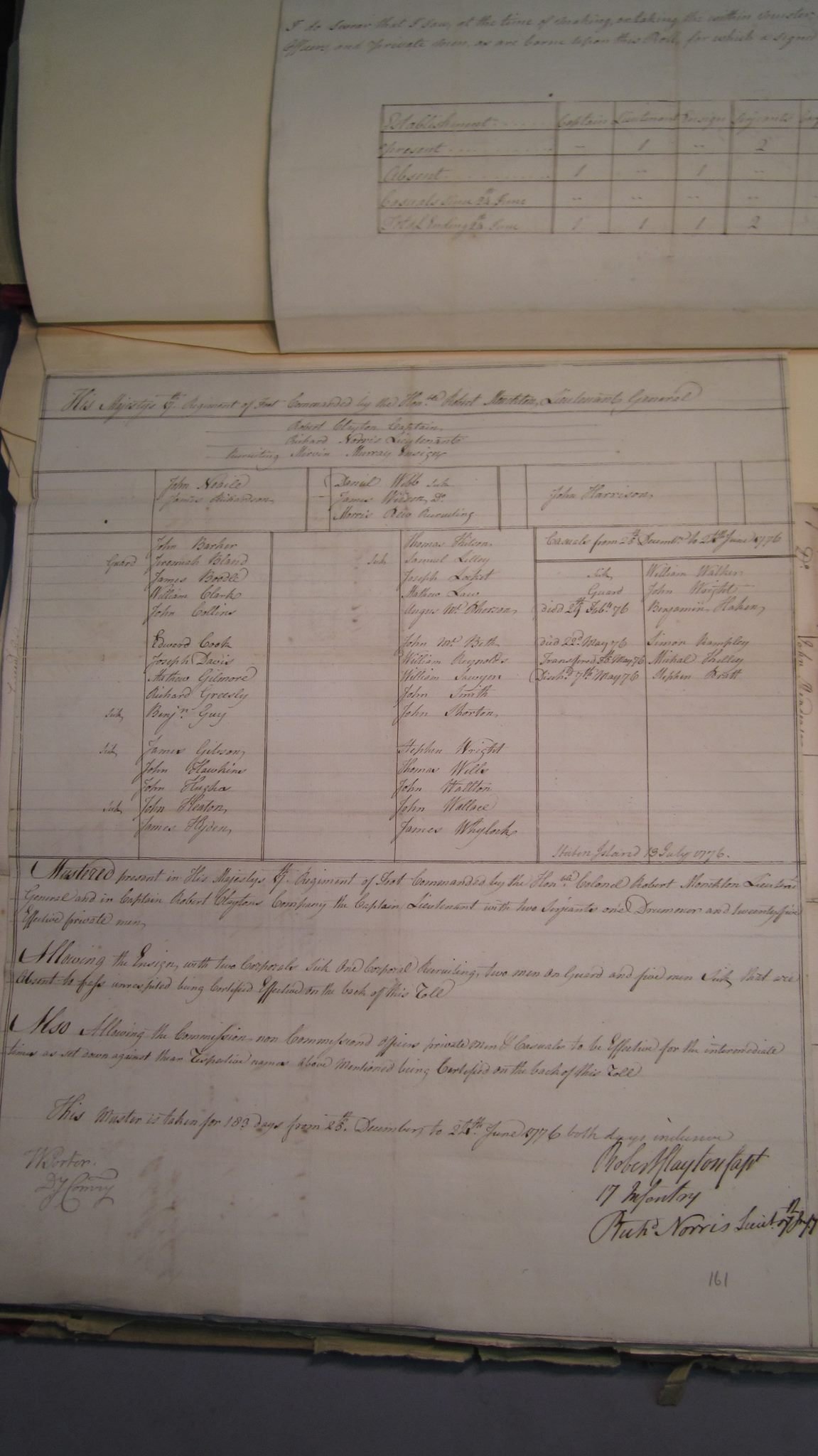

Dr. Mark Odintz Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

Photo by

Photo by

From the very first sewing party, January 2015.At this particular sewing party this weekend, we focused on trousers for new members and loaner gear trousers. The followers also worked on stays, caps, and setting up our camp-life page for the website. More to come, so be on the look out!Below are some pictures from the weekend. Enjoy!

From the very first sewing party, January 2015.At this particular sewing party this weekend, we focused on trousers for new members and loaner gear trousers. The followers also worked on stays, caps, and setting up our camp-life page for the website. More to come, so be on the look out!Below are some pictures from the weekend. Enjoy!