Music Made Easy: A Guide to Period Playing

As a folk music lover myself, I grew up around listening to jigs and contra style songs as my parents met and continued to go clogging when I was a kid. I'm very excited to introduce Tim MacDonald a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music and a good friend of mine. This post is filled with fun facts, images and tunes. Enjoy!

Mary - An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry

And for this reason, in every age, the musick of that time seems best, and they say, Are wee not wonderfully improved? And so comparing what they doe know, with what they doe not know, they are as clear of opinion, as they that doubdt nothing.

~Roger North, ca. 1726

Much of the look of a recreated 1770s camp can be recreated faithfully with relatively obvious documentation. The tin kettle hanging over the fire was copied from an original excavated at a military site. The crossbar that it hangs on was chosen after reading a paper that analyzed dozens of images and other accounts of period military cooking. The stew boiling in it was based off of a documented ration issue and a description in a soldier's journal. And so on and so forth. Gathering, evaluating, and applying all of these sources requires a tremendous amount of insight and plain old hard work. But there's usually a sense of how your interpretation measures up. Does your coat match an original? Well done!

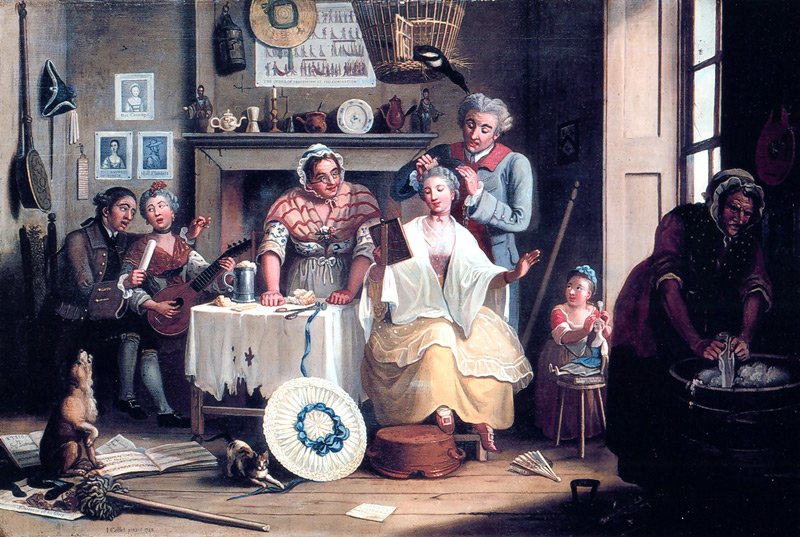

The sounds of that same camp, though, are much less concrete. In the 18th century as now, music was commonly-heard and well-loved. And in the pre-recording era, an even higher percentage of the population played an instrument, and musicians could be found everywhere from the drawing rooms of the upper class to the earth-floored houses of the lower class, from the taverns (many of which had loaner instruments available) to the  drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

- Get the equipment right. Many common instruments of today didn't exist in their current form in the 18th century. Much as an M-16 rifle is no substitute for a Brown Bess, a modern

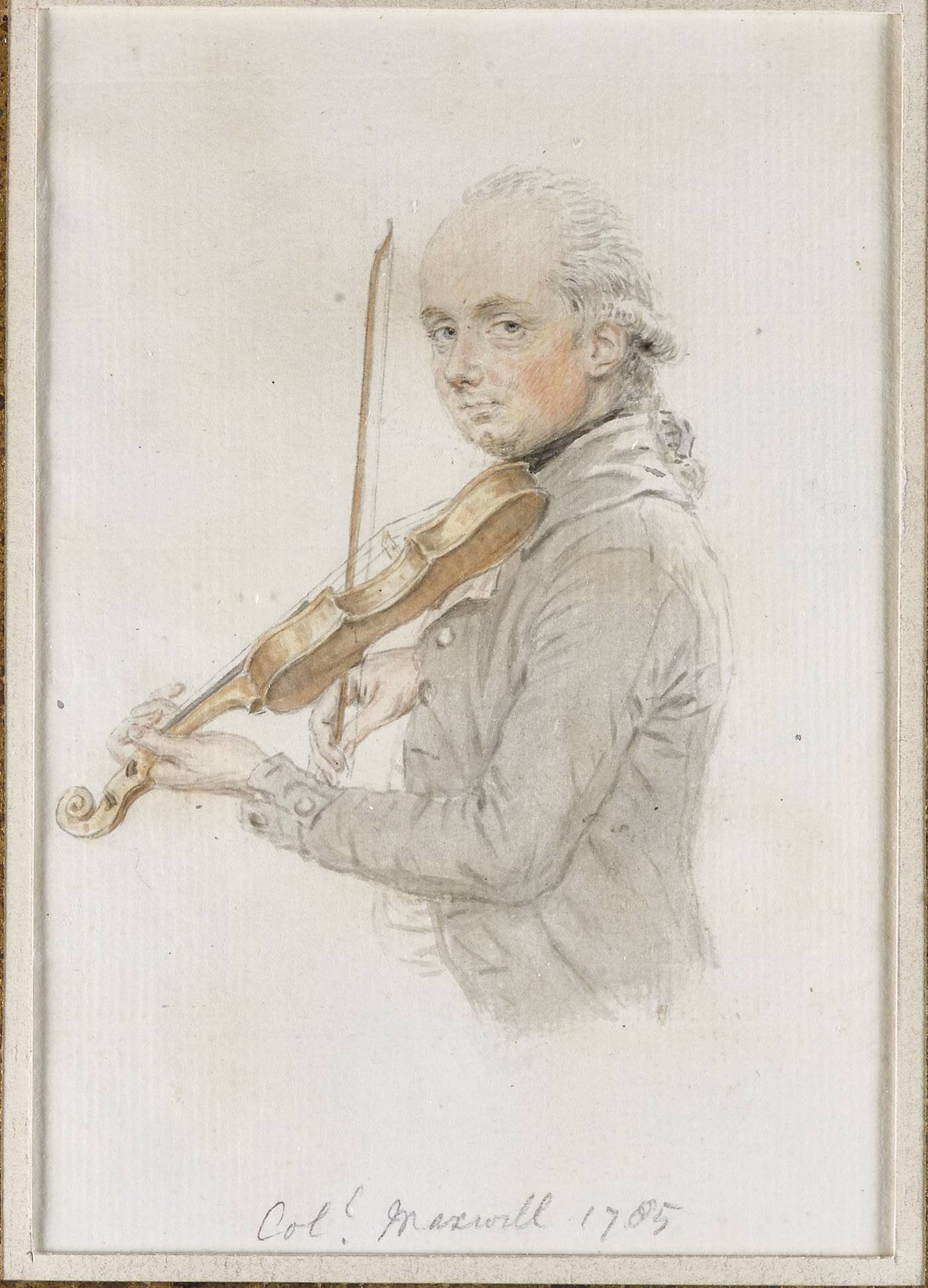

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment. - Forget about folk music. It's very tempting to learn folk tunes, reflect on how there's an unbroken tradition of playing them that stretches back to the 18th century, and then play them unaltered at events. Resist this temptation. First of all, tradition slowly mutates things over time, and 240 years of mutation adds up to a lot. Second of all, the term "folk music" is fairly problematic in an 18th-century context: there was no distinction between "folk" and "classical" players, everyone played everything (limited solely by their skill level and the functions they were playing for).

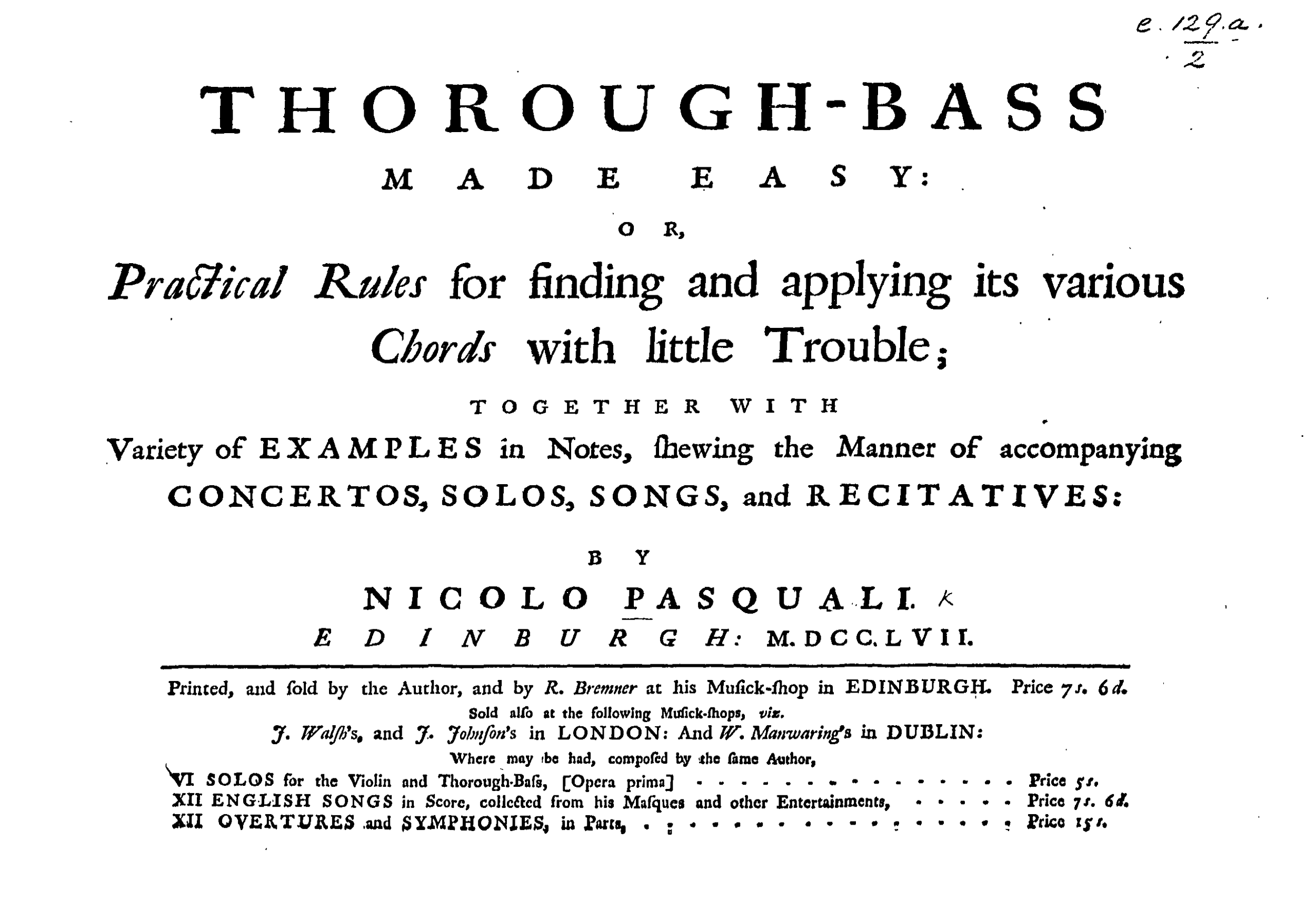

- Play the right tunes. Many pieces we consider "old" today actually originated inthe 19th century, and many period-correct tunes have been forgotten about. Fortunately, there's a wealth of surviving tune collections in both published and manuscript form. They can be found online at IMSLP, archive.org, the websites of good libraries (such as the National Library of Scotland), and elsewhere, or in person at major libraries (research-oriented libraries are usually better than lending libraries) or the office of a friend already involved in early music. What collections to look for first? Try searching newspaper archives for publication announcements, period accounts for tunes mentioned by name or catalogues of music collections of notable people (such as Thomas Jefferson) or sites (such as Williamsburg).

- Play them the "right" way. The catch-all term for playing historic music is HIP: Historically-Informed Performance. As alluded to above, it'd be unfair to call it HRP (Historically-Replicating Performance) or similar because that's impossible. But there's a big difference between letting the I stand for "Informed" and letting it stand for "Ignorant". What to do? Read period treatises on music-making (I've listed a few popular ones here). Read modern commentary on the philosophy of 18th-century musicmaking (The End of Early Music and The Weapons of Rhetoric) are good places to start. Read about how the tunes were used. If they were played for dancing, try to recreate the dances. Play a lot, experimenting with different interpretations (and everything that entails: different affects, different tempi, different ornamentation…). Recreate period-correct ensembles (violin + cello and one-keyed flute + harpsichord are two easy and popular options). I've been amazed at how I used to dislike certain popular tunes but eventually found an interpretation that made it all make sense and led to really compelling music. It's hard, but it's well worth it.

- Display 18th century musical values. This is linked with #4. Throughout the 18th century (and before)—and much less so today—the following was prized in music: a) Composing one's own music. b) Personal interpretations of the music, fuelled by a heavy dose of improvisation (quoth Mozart in a 1778 letter: "[The performer should play] so that one believes that the music was composed by the person who is playing it.") c) So-called "rhetorical" playing: performing as if the music was a speech being presented in public, not just a string of notes. What does this mean? Phrasing appropriately (adding "punctuation" between the notes), changing dynamics (nobody speaks in a monotone), and cycling through various affects (even a eulogy isn't sad for its entire duration—it'll have sad parts and angry parts and even funny parts and happy parts and so much more).

This is a very brief introduction to a very complex topic, but I hope it points you in the right direction! Happy musicking!!

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo Tim Macdonald & Jeremy Ward. When not involved with some aspect of music, he can be found running silly distances, studying silly languages (currently Braid Scots), helping out at church, or mucking about at an AWI reenactment.

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo Tim Macdonald & Jeremy Ward. When not involved with some aspect of music, he can be found running silly distances, studying silly languages (currently Braid Scots), helping out at church, or mucking about at an AWI reenactment.

Listen to Tim Macdonald recreate the sounds of the 18th Century

Tim & Jeremy Live at the Midwest Sing & Stomp VIEWTim & Jeremy Live Wife Jigs VIEW