Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

SUTTLING in the WAR for INDEPENDENCE

Suttlingin the period of the American Revolution does not change much from the previousconflict although information is a bit more abundant. There is an increase of rules and regulationsgoverning the practice(s) of the Sutler. Several studies of the subject have been done including works by John U.Reese, W. Tatum Ph.D. and the 18th Century Material Culture ResourceCenter. The one text devoted to thesubject of followers is Holly A. Mayer Ph.D.’s book Belonging to the Army(University of South Carolina Press, Columbia South Carolina). Dr. Mayer’s work is focused on theContinental side of the conflict but parallels surly can be drawn.

Thefirst regulation and perhaps most mentioned on either side of the conflict isthat only “One Sutler” per regiment or brigade will be allowed and that Sutleronly licensed upon the recommendation of the commander. I surmise that this was in response to eithermore Sutler’s attempting to attach themselves to the army (looking to turn aprofit) or as we will see a common occurrence is the over sale of Liquor to thetroops. In addition to the single sutlerrule, there is a strong statement that the Colonel of the regiment beanswerable for the conduct of the sutler appointed.

General Orders, W.O. Boston 22June, 1775 (5 Days After the Battle of Breed’s Hill)

“All persons belonging to, or followers of the Army, are forbid to sell spiritous liquors, excepting at the regimental Canteens, one and only one of them is allowed for each Regiment subject to the regulation of the Officer Commanding it; and as the appointment of the Sutler depends on the commanding Officer of the Corps, it is expected henceforward they will be answerable for the sobriety of the Soldiers under their Command, all other sources for Spiritous liquors but that of the Canteen, being effectually stopped up from the A G Officers and Soldiers by the Proclamation”

Thenext regulation that appears is in regard to provision, sale, quality,quantity, price, and time of sale of Liquor and other spirits.

General Orders, W.O. Boston14October, 1775

“The Commanding Officers of Corps not to allow their Sutlers to sell liquors to Soldiers, or any other persons who do not belong to their respective Corps; Upon a conviction of a disobedience of this order, the liquors will be destroyed, and the delinquent not have leave to sell any in the future. Women belonging to the Army convicted of selling Spiritous liquors, will be confined in the Provosts till there is an opportunity of sending them from hence."

Orderly Book H.M. 47th Regimentof Foot Camp at River Bouquet 16 June, 1777

“The Sutlers are not on any pretence to sell Rum or any other Spirits to the Men without a Written Order from a Commission’d Officer and never in less Quantity than a Quart”

Furtherclarifications were made including regulations against “pretend sutlers” whowere selling alcohol, and a clarification that Sutlers were to sell alcohol toONLY the soldiers belonging to the regiment the sutler was licensed to. Having drunk soldiers and thus placing directblame on the Sutlers is common, if not to say, correct. An infraction of the set regulations mostoften ended with consequences that were somewhat standard. The guilty Sutler would have their stockconfiscated and ordered to leave the camp. Also license revocation was possible and the most severe punishmentwould have been from 50 to 100 lashes “upon the bare back” to be “well laidon”. We also see a trend in therepeated requests for the sutler names to be taken down and sent toheadquarters. My impression is so thatthe provost guard or Serjeant Major of the army may try to better regulate theactivity of Sutlers. Many times guilty offenderswould simply move shop and open a Tipling House or Dram Shop nearto, or even within the camp confines.

*ATipling House was a term used to describe a house, stall or booth in whichliquors are sold in drams or small quantities, to be drunk on thepremises. Often associated with illegalselling and consuming of liquor.

*A DramShop, or dramshop in this period is a bar, tavern or similar commercialestablishment where alcoholic beverages are sold. Traditionally, it is a shopwhere spirits were sold by the dram, a small unit of liquid.

These termsare common when regulations were being written or orders issued. Given theexamples below.

General, Sir William Howes Orders 23January, 1776

“The Commanding Officers of Corps to Suppress all Dram Shops in their Respective Districts that are not licensed by Brig.-Gen. Robertson.”

General Orders War Office RhodeIsland11 December, 1777

“Whereas the great Drunkenness that prevails among the Soldiers, proceeds from the Soldiers wives being allowed to keep little shops out of the districts of their Regiments, the Commanding Officers will give directions that they are not permitted to live out of the quarters of the Regiment they belong to.”

Standing Orders H.M. 71st Regiment of Foot15 August, 1778

“Whereas the great Drunkennes that prevails among the Soldiers, proceeds from the Soldiers wives being allowed to keep little shops out of the districts of their Regiments, the Commanding Officers will give directions that they are not permitted to live out of the quarters of the Regiment they belong to.”

Both the Continental and British Army developed “Articles of War” with the Americans “borrowing” much from their British cousins. In the British Articles of War, regulations were set down for the governance of Sutlers and we can see some similarities and differences between the two forces. In Section XIV, Article 23 of the British Articles: it states that sutlers, retainers, and others serving with the army were subject to orders “according to the Rules and Discipline of War”. A definition that allows for a large amount of “wiggle room” for those commanding. The American Articles on the other hand were more exact in the governance of the sutlers. Article 32 of the American Articles states: they are “subject to the articles, rules, and regulations of the Continental Army”. A more precise painting of the subject vs the broad strokes employed by the British, however as the war progressed the Americans re-evaluated these strict definitions, so in 1776 the Second Continental Articles of War established that Sutlers would be governed “according to the rules and discipline of war”, an echo of the British articles.

TheContinental Congress also closed a gap form the 1775 regulations in 1776. Unlike the British model that permitted allofficers, soldiers, and sutlers to bring into garrison “any Quantity or Speciesof Provisions, eatable or drinkable, except where any Contract or Contracts areor shall be entered into by Us, or by Our Order, for furnishing suchProvisions”, the American rules had no such provision, in 1776 the change is made, allowing “eatable ordrinkable” provisions not already contracted for be brought into camp. This article was further amended in 1777 toonly include “eatable” provisions. A bittoo much alcohol being offered perhaps. Additional rules included ones thatprohibit the sutler from staying open past 9 O’clock and not opening “before thebeating of the reveilles, or upon Sundays, during divine service orsermon”. Price gouging was alsoaddressed and in the American Continental orders, the officers were to see toit that soldiers were supplied “with good and wholesome provisions at themarket-price”, and in Article 4, the sutlers received like protection. Officers were to be sure that “exorbitantprices for houses or stalls, let out to sutlers” not be charged.

From“Belonging to the Army” Dr. Mayer’s states:

"Sutlers were merchants or traders permitted to sell provisions to the troops. Business-minded individuals, whether self-employed peddlers or representatives of some of America's bigger mercantile concerns, saw opportunity beckon as early as the spring of 1775 when New England militia units camped around Boston. They carted their goods in and set up shop. Some then attempted to stay with the forces that were united into the Continental Army”

I believethere are few differences between Sutlers following the Continental vs theBritish Army in America owing to the fact the role of the Sutler having beenmore evolved within the British establishment simply due to the fact they hadbeen doing this “Sutler Thing” longer.

We occasionally get a glimpse into what day to day life was like. In The History of Henry Esmond by William Makepeace Thackeray, originally published in 1852. A story of the early life of Henry Esmond, a colonel in the service of Queen Anne set against the backdrop of late 17th- and early 18th-century England. Although fiction, the tale related here may help to demonstrate the role the sutler played in the life of the soldier in the 18th century.

Turning from fiction, there is nothing much more exciting than finding a “firsthand” account regarding either a sutler or sutler activity. In the memoir “Westward into Kentucky, the Narrative of Daniel Trabue”, Edited by Chester Raymond Young, The University Press of Kentucky. Trabue in 1827 wrote down his many stories from his life, now the 148 pages are preserved in the Lyman Copeland Draper manuscripts in the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Included in these pages are the narrative of his time spent in and around the Continental Army specifically during the Yorktown campaign in 1781, where he joins the Militia and soon volunteers to carry dispatches to “General Layfatte”. In one of his recollections he tells the tale of an interaction with a tavern keeper while carrying dispatches. After getting a drink he sees a mounted British patrol coming his way, Trabue makes his escape and the tavernkeeper shouts “Don’t get ketched!” When he reaches the General and delivers his dispatches and after being asked many questions, he “applied to him for a permit to be a sutle to his army.” Which “He [Lafayette] imedeately had one wrote”. Trabue, permit in hand, now must find something to sell. He went into the camps and observed the different men “selling spirits.” and finds a “Dutchman” who had just arrived with “a fine teame and a good load of Brandy and Whiskey and two very large sacks of sweet bred.” Trabue seeing an opportunity asks the Dutchman “Have you a permit to sell your spirits?” which he answers in the negative. He lets the Dutchman know that he heard that any illegal sales would result in confiscation of all possessions including wagons and spirits. He [Trabue] tells him he has a permit and offers to go “halfs” with him? The Dutchman is unimpressed and ignores the offer, that is, until in Trabue’s words, “here comes the Ajatent and says, ‘whoes wagon and spirits is this?’” Needless to say, the Dutchman takes up the offer, and the guard is turned away. Trabue later goes on to describe how all the other wagons and spirits were impressed and the two “made a very handsom profit.” However, this good fortune was short lived. Once out of camp Trabue’s new business partner decided he would not go into the camp again for fear of losing his wagon, “he would take his wagon home and pull of[f] the wheels”. This left Trabue looking for a new opportunity. Finally, he asks General “Fayette” for leave to go home and find a team, wagon and anything else he can sell. He finds Brandy and Rum however that’s the last mention of his adventures as a Sutler in his narrative.

Includedhere are the American Articles of War that pertain to Sutlers in 1776. These having been referenced prior. Inreading them an even better understanding of the role of the sutler may begained.

AMERICAN ARTICLES of WAR September 20th 1776

SECTIONVIII

Art. 1.No suttler shall be permitted to sell any kind of liquors or victuals, or tokeep their houses or shops open, for the entertainment of soldiers, after nineat night, or before the beating of the reveilles, or upon Sundays, duringdivine service, or sermon, on the penalty of being dismissed from all futuresettling.

Art. 2.All officers, soldiers and suttlers, shall have full liberty to bring into anyof the forts or garrisons of the United American States, any quantity orspecies of provisions, eatable or drinkable, except where any contract orcontracts are, or shall be entered into by Congress, or by their order, forfurnishing such provisions, and with respect only to the species of provisionsso contracted for.

Art. 3.All officers, commanding in the forts, barracks, or garrisons of the UnitedStates, are hereby required to see, that the persons permitted to settle, shallsupply the soldiers with good and wholesome provisions at the market price, asthey shall be answerable for their neglect.

Art. 4.No officers, commanding in any of the garrisons, forts, or barracks of theUnited States, shall either themselves exact exorbitant prices for houses orstalls let out to settlers, or shall connive at the like exactions in others;nor, by their own authority and for their private advantage, shall they lay anyduty or imposition upon, or be interested in the sale of such victuals liquors,or other necessaries of life, which are brought into the garrison, fort, orbarracks, for the use of the soldiers, on the penalty of being discharged fromthe service.

While at Valley Forge orders were given that a board of General Officers meet and decide upon the rules for Suttling. The results of this meeting were as follows and gives us an idea as to what alcohol was available during the winter of 1777-78. This also tells us that tobacco in several forms was available.

HeadQuarters V: F: January 26th 1778.

MajorGinl. Tomarrno Grebn

BrigadierMcIntosh

FieldOffV . . . LT Col Gray. Majr Braddish

B: M: MClurb

A BOARDof Genl Officers having recommended that a Sutler be appointed to each Brigadewhose Liquors shall be inspected by two Officers Appointed by the Brigadier forthat purpose and those Liquors sold under those restrictions as shall bethought reasonable the Commander in Chief is pleased to approve the aboveRecommendation and to order that such Brigade Sutlers be app^ and Liquors soldat the following prices and under the following Regulations each

Brandyby the Quart 7/6 by the pint 4/ By the Jill 1/3

Whiskyand apple Brandy 6/. p quart 3/0 p pint and 1/ p jill

Cyder1/3 p quart

StrongBeer 2/6 p quart

CommonBeer 1/ P quart

Vinegar2/6 p quart

AnySutler who shall be convicted before a Brigade Court Martial of having demandedmore than the above rates or of having adulterated his Liquors or made use ofDeficient Measures shall forfeit any Quantity of his Liquors not ExceedingThirty Gall! or the value thereof at the forgoing rates, The fourth part of theLiquors or the value thereof so forfeited to be applied to the Informer and theRemainder of the Liquor to be put into the hands of the person Appointed by theBrigadier who shall deliver it out to the Non Comissf and privates of theBrigades at one Jill p man p day, If Money to be laid out in Liquors or Necessariesfor the N : Comissiond Officers & privates of the Brigade and distributedin due and equal proportions,

TheBrigade Sutler is also at Liberty to Sell leaf Tobacco at 4/ p lb.

PiggTail 7/6 p lb hard soap 2/6 p lb But noother Articles rated for the publick Market shall be sold By him or any personacting Under him on any pretence wnatever.

Sutlerswere not confined to the large camps of either army, they followed the army allthe way to the far reaches of the new United States. On the western frontier near Pittsburgh andFort Pitt was a smaller outpost who found itself the victim of someunscrupulous vendors.

Orderly Book of the EighthPennsylvania RegimentOctober, 1778 - May, 1780

“11 Oct 1778 HEAD QUARTERS, FORT McINTOSH, As some narrow-minded persons, who not regarding the good of their country, nor yet the rules of common honesty, have presumed to approach this camp, and in defiance of all order & regularity, without license, at the most exhorbitant price sold liquor to soldiers: Therefore in order to deter all persons from committing the like abuses for the future: the Col. Commt doth direct that no person whatever shall presume to sell liquor to either officer or soldier without first having obtained leave from the Commanding Officer present, or from the General...the Col. Commt doth promise to give reward of 5s pr gallon to any soldier who shall give the earliest notice of such trespassers, & the liquor so seized shall be issued to the troops."

"Orderly Book of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment" in Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio 1779-1780 (Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison), Appendix pages 431-459 [2NN109- 178]. (Numbers in [ ] refer to specific document numbers within the Draper Manuscript Collection.)

Orderly Book of the EighthPennsylvania RegimentOctober, 1778 - May, 1780

22 May 1780 - HEAD QUARTERS, PITTSBURGH, ...Whereas it has been represented to the Commandant, that soldiers are frequently found among the inhabitants of Pittsburgh much disguised in liquor, even after tatoo beating; he therefore directs that officers of the day do take with them at least two files of men from the fort guard, & at least twice a night patrol the streets & make prisoners of the soldiers found absent from their quarters after beating the tatoo - except where such soldiers have permission in writing from a field officer commandg a regt, to remain at their quarters in town & are not found in abuse of the indulgence....The officers of the day are to sieze all liquors in the possession of persons vending them to the troops or others, agreeably to form orders, & report their names in order that those tippling houses may be pulled down & destroyed."

"Orderly Book of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment" in Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio 1779-1780 (Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison), Appendix pages 431-459 [2NN109- 178]. (Numbers in [ ] refer to specific document numbers within the Draper Manuscript Collection.)

In 1782,the QMG Timothy Pickering gives the following regulations:

"Regulations for the Government ofSutlers

1st

Allthe liquors and provisions which a sutler shall expose to Sale shall be ofgood & wholesome quality & for this reason subjected to theInspection of the quarter master general, or such officer as he shall appointfor the purpose.

2d

Theprices of the articles shall be reasonable, and to prevent imposition, a listof the prices shall be posted up at his quarters.

3d

ForLiquors or other articles sold to noncommissioned officers & soldiers,artificers and waggoners, nothing shall be taken in payment but money.

4.

Nosoldier or others described in the 3d Article are to be suffered to remainTipling about a sutler's quarters.

5th.

Atthe beating of the tattoo, each sutler is to shut up his stores, and sellnothing more until after Reveillee the next morning.

6.

Eachsutler is without delay to report to the quarter master general the placewhere he fixes his quarters.

7.

Theseregulations are to be posted up by each sutler in a conspicuous place at hisquarters.

CampSept 8. 1782 Tim. Pickering

QMG"

(Timothy Pickering, "Regulations for the Governmentof Sutlers," 8 September 1782, National Archives, Numbered Record Books,vol. 84, reel 27, pp. 96-97.)

In conclusion, interpreting aSutler either British or Continental, Grand or Pettit, Man or Women can be arewarding and enjoyable endeavor. Creating a sound, well researched impression can be a challenge, yet ultimatelyworthwhile. I have presented here only asmall amount of what I and others have found, and my humble interpretation ofthat information. I take my “hobby”seriously and strive to present to the general public and my peers the bestimpression I am able to create. I findmy desire from an undying respect for those whom I try to portray, I will neverbe able to recreate their lives but I can give my all to accurately reproducewhat their lives may have been like. Iwill close with a quote form Dr. Mayer’s text:

"They were people who were not officially in the army: they made no commissioning or enlistment vows. What kept them with the army was their desire to be near loved ones, to support themselves, and/or, in some cases, to share in the adventure. This diverse company encompassed both patriots, those who embraced the cause of independence with a fervor equaling or surpassing that of any soldier, and leeches, who were there merely for personal gain. A few prostitutes. and scavengers trailed after the army, but family members, servants, and other authorized civilians outnumbered them by far.”

BRANDYN CHARLTON

Brandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 23 years. He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area. Beginning in 2020 he will bring his sutler impression to the 17th Regiment of Infantry in America as a member and follower of the Regiment.

The Necessary Evil of Sutlery

“ASutler or Suttler” in an 18th century military context has become amore common impression for many reenactors as of late. I surmise, which is true in my case, thedecision to start representing a Sutler has grown out of the realization that Ican no longer do a proper military impression be it my age or otherinfirmities. However, this does not meanwe want to move away from the “progressive” movement or would in any way, Nothold our new impression up to the rigorous standards set forth by numerousorganizations. So, what is one to do? Well if you are fortunate like I am and the military unit you belong to hasa civilian or “camp follower” branch you are in luck. The only thing now is how to justify yourpresence either in or very near a military camp. This has a bit of a gender componentinvolved. If you portray a woman incontext you can more easily attach yourself in a variety of roles, but as amale the opportunities are a bit narrower. That’s where the Sutler can fill the void. Let me say women were often Sutlers and its nota male only impression, just that it is an area I take keen interest in. Whether it be a “petit sutler” or a “Grandsutler” the ability to portray a civilian who has reason and purpose to beinside or near a military camp has sparked new interest in the topic ofSutlers’ and Suttling.

In this piece I will give my personal opinions and assumptions based on the research, share what I have found in my research, and include some research by others on the topic. This is in NO WAY an all-inclusive guide or definitive work on the subject. However, it is a start to guide others or just make them better informed so in turn they can better inform the public we interact with.

Theterm “Sutler” finds its origin in the late 16th century Dutchlanguage Soetelen – Soeteler meaning “one who does dirty work, a drudge, lowwork”. As an English noun the worddescribes a civilian provisioner to an army or post often with a shop on thepost.

Johnson, Samuel “A Dictionary of the English Language” London, 1755

SUTLER: N,f. (soetler, Dutch; sudler, German): A man that sells provisions and liquor in Camp. PUBLICAN: A man that keeps a House of General Entertainment.

Oneof the first popular uses may have been in 1599, in Shakespeare's HenryV.

“For I shall sutler be / Unto the camp, and profits will accrue” - Pistol

Sutlers were a “necessaryevil” to the armies of the 18th centuries, many if not all personswho chose this profession were looking to make a profit. The age-old idea of supply and demand playedwell in the military campaigns of the century. Although the military and/or government would supply the men with thenecessities of life they were far from all that was needed to sustain life oncampaign, or in garrison. So enters thesutler and with them enter the rules to govern these convenient stores of the18th century military.

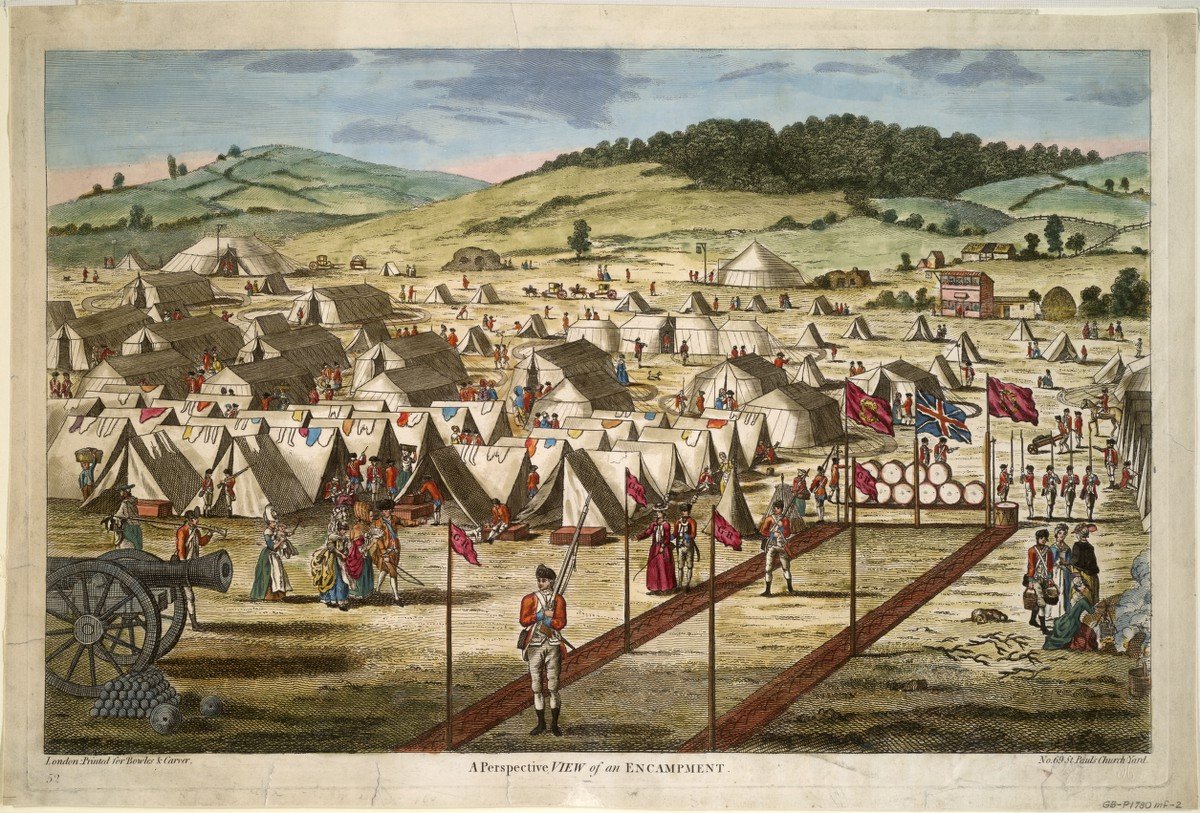

Consultation of An Essay on Castrametationby Lewis Lochee and A System of Camp-Discipline, Military Honours,Garrison-Duty, and other Regulations for the Land Forces. Collected by aGentleman of the Army, gave some very specific rules and regulations regardingthe practice. Instruction for Sutlersand location of Sutlers’ tents within an encampment are the primary focus ofmuch of the text and illustrations. An additional source for the regulation ofSutlers’ and Petit Sutlers’ for the period comes from Bland’s Treatise onMilitary Discipline. Whereinstructions are given for the layout of a proper camp including a location forthe “Grand Sutler” tent, just beyond the tents of the Batman and lying beforethe camp kitchens, and beyond the kitchens the area designated for the PetitSutlers.

From: An Essay on Castrametation by Lewis Lochee

Because I began my reenacting journey in the period of the French andIndian War, I have a strong interest in that period so naturally I began myresearch there. For a deeper look togain some context as to what the Sutler did, I chose my starting point to bethe earliest primary resource in my personal library, The Papers of HenryBouquet, Vol. II, The Forbes Expedition. Herein is just a small part of what I found.

Ina letter written from Bouquet to Forbes from Carlisle 7th June 1758describing the preparations for the upcoming campaign Bouquet writes

“The number of merchants asking to follow the army makes me think that if you offer some encouragement, you could engage workmen of useful trades, such as tailors, saddlers, gunsmiths, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, etc., to come with the army without wages and of their own accord. This would be very helpful in the woods and would save paying those people.”

Althoughthe specific term “Sutler” is not used in this example, I make the inferencethat “merchants” would include those who wish to ply the trade of Sutler to thearmy as the source of the primary requests. So much so that Bouquet thinks that offering up the opportunity to makea profit will entice others “of useful trades” to come along and save thegovernment the expense of paying for such services.

Thenext mention of Sutlers is in a letter from Bouquet to Forbes again, this timefrom Reas Town Camp, 8th August 1758. While giving his report to Forbes, Bouquetwrites:

“Yesterday I had word that three sutlers’ wagons which were going from Juniata to Fort Littleton without escort, were attacked beyond Sideling Hill by nine Indians who scalped two wagoners and took two prisoners… On hearing of the first, I sent out a party of thirteen Indians and seven volunteers to cut them off by an ambush on the Frankstown road.”

There is a lot that can belearned in this entry, first the wagons are describes as “sutlers’ wagons”which makes them civilian and not military property. Also, he notes that they were “withoutescort” making it seem a private venture, perhaps an escort would have cost thesutler and they decided it was an un-necessary expense. Something they will think of next time,provided the sutler themselves were not among the scalped or captured? We can also assume that the two posts“Juniata” and “Fort Littleton” had sutlers selling necessities to the army evenif only in passing through. Lastly, thefact Bouquet sends out a party to ambush the raiders leads me to believe thatthe sutlers were important enough to risk military forces, of course it wouldhave not been unusual for a response party to be sent out on the information araid had occurred if only to reconnoiter.

Forthe largest and most extensive piece of primary documentation I have found thusfar is the entry on 10th August, 1758 titled “RATES AND PRICES ATRAYSTOWN”.

Thecorresponding orders to produce the list I believe are found in this entry intothe Orderly Book:

8th of August, 1758:

“As it is necessary to settle the Prices of the Sutlers Goods the Commanding Officer of each Battalion or Brigade Major Shippen & Capt Young, are desired to meet at Col Burd’s Tent at 1o’Clock, who are to allow them a reasonable profit according to the different Distances for Rays Town, over the Hills & upon the Ohio – and to make their Report to the Commanding Officer.”

Tothis date using the list described as a guide, I have been able to acquireactual or a “representation” of almost all the goods listed. When I refer to a representation, I may nothave the actual quantity given in the list so I have settled for an examplei.e. “Madeira Wine” using a period wine bottle even though the quantities arelisted in gallon measurements leading me to believe they were probablydelivered in casks. I have also found some interesting items on this list thattook a little research to determine what they are. A “Vidonia” is a Dry White Wine, from theCanary Islands. Its placement on thelist gives it away as some type of wine. “Mim” I am not 1oo percent on this one, it could be a type of mixeddrink? “Tamarinds” from the tamarind tree are a pod-like fruit thatis used in cuisines around the world. Ifyou like WorcestershireSauce and HP Sauce, this fruit is found ineach. And lastly, “Gammons” are a side of bacon or the lower end of a side ofbacon.

Whilethis list is a great resource and gives idea as to what was available in 1758on the Pennsylvania/Ohio Frontier, a real gem of information is to be found inthe margin of page two. The following instructions are given:

“All Sutlers to provide Dinner & Suppers for the Officers of the Corps to which they belong, they giving in their Rations & paying 6d pr day for Cooking also Paying for what Liquors they drink.”

Thisis one of the first primary source documents to my knowledge that mentions whata sutler was doing other than the obvious selling of wares. Armed with this piece of information those ofus who search for more and more relevance for being with an army can state that(at least in 1758) sutlers were also responsible for cooking the rations of theOfficers at a rate of 6 pence per day and the said Officers were instructed topay for what they drank. This in turncan lead to many interpretive opportunities for the public; cooking,interacting with officers, serving, both food and beverages. From a vignette standpoint there can becomplaints about unpaid bills, the exchange about the quality of the food, theinteractions between officer class and either enlisted or other civilians etc.

Anotherinstance the next year in May 1759, Bouquet writes to George Stevenson, theprothonotary of York County that as it might be worthwhile to advertise

“to encourage People to carry at their own Venture several necessarys to the Army, I beg you would let me Know what Prices you think should be offered at Bedford, Ligonier, and Pittsburgh” for flour, oats, Indian corn, rye, whiskey, pork, cattle, sheep, and hogs.”

He continued that sales in camp of small items such as;

“Butter, cheese, Fowls, Fruit Vinegar Wine &c” were welcome, “but no Spirit except for the King’s Stores.”

Thenext text consulted is the Colonel Henry Bouquet Orderly Book, 17 June –15 September, 1758. The first entrydeals with military rules and regulations. On 22nd June 1758, Camp at Juniata:

“If any Suttlers, Agents of Provisions, or others have Persons to send to the Settlement, They must not leave the Camp without a Pass from the Commanding Officer-"

Onthe 24 of June orders issued from the Camp at Reas Town the Standing Ordersduring the Campaign-

“1st All Horses belonging to the Officers, Waggoners, the Train of Artillery, Sutlers, or any other Person whatsoever to be sent with the Cattle to the Pasture every morning at Revallee Beating…”

Onthe 3rd of July, from the Camp at Reas Town the order was issuedthat:

“All the Dearskins that are Actually or shall be brought into Camp are to be Delivered to the Artillery Store as soon as they are dried & stretch’d, as they are wanted to make Mockessons for the Men that go on Party’s…no Sutler or any Person whatsoever is permitted to buy any –"

Thetopic of alcohol has only been mentioned briefly up to now in this primarysource. Alcohol is a primary commoditythat Sutlers are selling and we will look specifically at that subject at thispoint. Interestingly on the 18thJuly, and again from Raes Town the order of the day begins with an order aboutthe purchase of Rum.

“No Soldier shall buy any Rum from the Suttlers without an Order in Writing from the Officer Commanding the Company, and Quantity never to exceed more than a Jill Pr Day for one Man.”

OnAugust 10th we find a Sutler being charged and brought to Courtmartial:

“A Court martial of the Line tomorrow Morning at 9 oClock to try a Suttler for selling Liquors without proper orders. – Ens. Gradon to Prosecute him.”

“26th August 1758 Camp at Rays Town

The Liquors and Goods bought from the Suttlers are to be paid at the rates fixed by the Committee of which each Corps is to take a Copy from the Brigade Major.”

Herewe have suspect evidence of some unscrupulous behaviors of the Sutlers, perhapscharging more for goods than what has been set. This example is a good one to discuss with the public about theregulation of free trade, and could be some of the seeds of rebellion? The Sutlers are looking for profit and perhapsnone were members of the “committee” that fixed the prices? They are under military regulation in orderto have access to the army, but this oversight may at times seem restrictive totheir business. The Suters are also anecessary component to having an army in the field, they supply many of theitems the army could not provide, and some items they (the army) wished theydid not. Again, on the 29th of August things have become worse andnow there is an issue with giving Liquor to the Indians, as noted with theextensive entry into the Orderly Book:

“Notwithstanding the several Orders against giving Spirituous Liquors to the Indians, many of them were drunk yesterday; The Commanding officer thinks it proper to repeat General Forbes Orders respecting it vizt .”

Oneparticular Sutler worth mentioning is Samuel Blodget, of note not so much forhis “suttling” skills but where he was and was able to do because he was aSutler serving for General Johnson’sforce on the Lake George. His famearises due to the fact he viewed the Battle of Lake George personally then drewand published The First American Battle Plan A map of the 1755 Battle ofLake George in New York, fought between the French and Native American(Iroquois) forces under the command of General Ludwig August von Dieskau, andthe British and provincial troops under Sir William Johnson. The highlydetailed pictorial view and map, depicting the “First Engagement” and the“Second Engagement”, was published barely three months after the battle, andlater re-engraved and published by Thomas Jefferys in 1756 in London. Samuel was in the Louisburg campaign of1745; was Sutler in Crown Point expedition in 1775; in 2nd expedition to CrownPoint 1757; Sutler at Ft. William Henry when Gen. Webb withdrew his troops. In1758 he rejoined the army; there as quartermaster as late as Oct. 1758.

Name: Blodgett, Samuel (1724-1807)

Title: Sutler, Crown Point Expedition

Sutler, Fort William Henry

Quartermaster, British Army

Collector of Excise, New Hampshire, 1770

Judge, Inferior Court of Common Pleas

Surveyor, Colony of New Hampshire, 1772

Member, New Hampshire Legislature, 1778

Selectman, Town of Goffstown, 1781

Presentedhere is just a small sampling of what is available for the period of the 7Years War or French and Indian War and there is much more to be discovered. The next instalment of this post will includesome observations and research pertaining to Sutlers in the period of theAmerican War for Independence.

BRANDYN CHARLTON

Brandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 23 years. He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area. Beginning in 2020 he will bring his sutler impression to the 17th Regiment of Infantry in America as a member and follower of the Regiment.

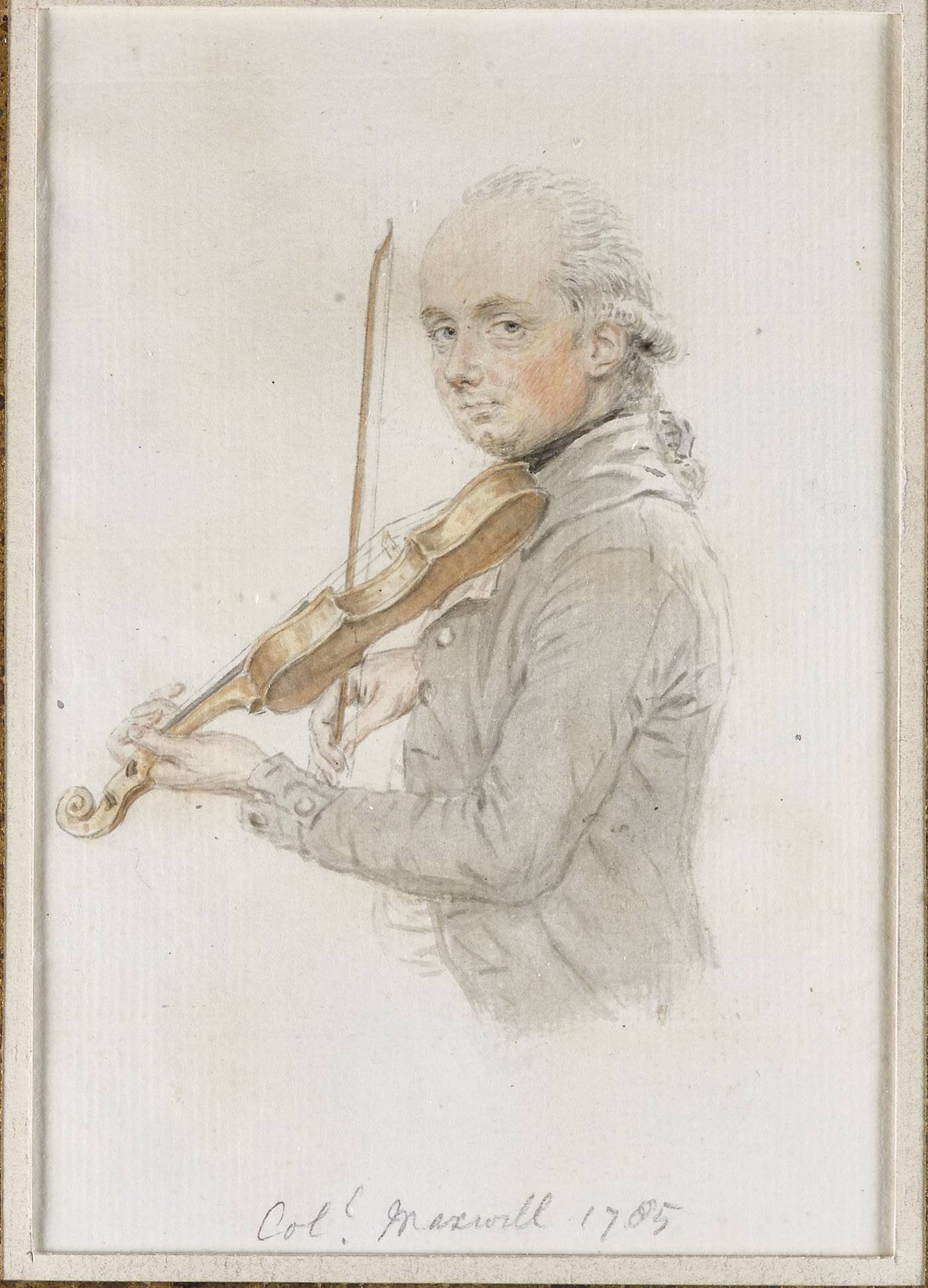

Bands of Music in the British Army 1762-1790. Part 3

In the previous two postings, we've looked at what a band was, who were in them, what types of music a band played, and what kind of ceremonies they played at. Perhaps most interesting to those lovers of material culture and military uniforms is what these bandsmen wore.

The uniform of a bandsman varied depending on the regiment. These men were not drummers and fifers so the rule of reversed facings does not apply to them. Ultimately, the uniform of the band was left up to the officers paying for them. One way to see what they wore is through deserter ads. This first one comes from our very own 17th:

Deserted from his Majesty’s 17th regiment of foot, quartered in Perth, John Humphreys musician, aged twenty years, size five feet six inches one-half, very swarthy complexion and jet black hair, black eyes, hollow cheeks, has a stoop in his shoulders, slender bandy limbed, has a very hoarse voice, talks thick, plays well on the French horn and fife; had on when he deserted the musician’s uniform of the regiment, viz. a scarlet frock, with white cap [sic - cape] and cuffs laced with silver, with white buttons having the number of the regiment, white cloth waistcoat and breeches, silver laced hat. He was apprehended (but escaped) on Wednesday the 7th in the Canongate; had on a bonnet, black coat, and wore a long staff in his hand.[13]

It's important to note that the bandsman is not in reverse facings. These men were not drummers and fifers and were not held to the same rule that made them reverse colours. For most regiments, the bands simply kept the same colour coats as the enlisted and officers. The band of the 22nd Regiment did the same as the 17th. Their band wore red coats with the regiment's buff facings, buff waistcoats and breeches.[14]

Another deserter ad from the 21st Regiment or Royal North British Fusiliers describes:

JOHN GRANT, aged 23 years, 5 feet 2 3/4 inches high, born in Beverly, in Yorkshire, England, by trade a jockey, has brown hair, grey eyes, fair complexion, a little pitted with the smallpox, and very thin made; had on, when he deserted, his uniform blue jacket, turned up with a red cape, and cuffs. Whoever apprehends and secures the above deserter, shall, by giving proper notice to Captain NICHOLAS SUTHERLAND, Commanding Officer of the said regiment, at Philadelphia, receive ONE GUINEA reward, over and above what is allowed by Act of Parliament for apprehending deserters.

N.B. He is supposed to be gone to Maryland, as he has a wife and a plantation in that province.[15]

The most interesting fashion trend of the 18th century comes from the Turks. Janissary clothing and g became incredibly popular in bands of music. Cymbals and jingling johnnies, long poles with numerous bells, became common sights. In the image below attributed to Thomas Rowlandson, the drummer and the cymbal both wear turbans in the Janissary fashion.[16]

An even more striking example Janissary fashion is exhibited in the portrait of John

Fraser, a percussionist in the Coldstream Guards. He wears a large turban with feathers sticking out of it. His red coat features silver lace and tassels. His sleeves are red in the upper arm but turns into a white fabric. His instrument, the tambourine, is a direct import from Janissary music. Bands of music were integral to the martial music of the British Army. Stemming from the Harmoniemusik movement of the 18th century, regiments adapted the instrumentation to fit their needs. The talented soldier/musicians of these bands played everything from military marches to operatic symphonies. To set them apart from soldiers and drummers, their uniforms reflected the tastes of their officers as well popular movements in late 18th century pop culture.

Fraser, a percussionist in the Coldstream Guards. He wears a large turban with feathers sticking out of it. His red coat features silver lace and tassels. His sleeves are red in the upper arm but turns into a white fabric. His instrument, the tambourine, is a direct import from Janissary music. Bands of music were integral to the martial music of the British Army. Stemming from the Harmoniemusik movement of the 18th century, regiments adapted the instrumentation to fit their needs. The talented soldier/musicians of these bands played everything from military marches to operatic symphonies. To set them apart from soldiers and drummers, their uniforms reflected the tastes of their officers as well popular movements in late 18th century pop culture.

When the 23rd Regiment was inspected on May 27, 1768, Major General Oughton said:

"The band of Musick very fine. The whole perfectly well cloathed and appointed."[17]

After John Rowe attended the concert of Fife Major McLean in Boston, he wrote in his diary that;

"there was a large genteel Company & the best Musick I have heard performed there."

These bands were designed to impress their officers and audiences from the songs and instruments they played down to the lace on their coats.[18]

Footnotes: [13] Edinburgh Advertiser, 9 October 1772. Courtesy of Don Hagist[14] Don Hagist, "Notes on Bands of Music in the British Regiments," Originally published in The Brigade Dispatch, Volume XXVII, No. 1 (Spring 1997), pp. 17-19.[15] Pennsylvania Gazette, December 12, 1771. Courtesy of Don Hagist[16] For further reading on Turkish influence on European society, see Edmund A. Bowles, "The Impact of Turkish Military Bands on European Court Festivals in the 17th and 18th Centuries, " Early Music 34, no. 4 (2006): 533-59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137306. Raoul F. Camus, Military music of the American Revolution, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977[17] Sherri Rapp, British Regimental Bands of Musick: The Material Culture of Regimental Bands of Music According to Pictorial Documentation, Extant Clothing, and Written Descriptions 1750-1800, Accessed September 4, 2017, https://www.scribd.com/presentation/215381883/British-Bands-of-Musick[18] John Rowe, Anne Rowe Cunningham, and Edward Lillie Pierce, Letters and Diary of John Rowe: Boston Merchant, 1759-1762, 1764-1779, Boston, MA: W.B. Clarke Co., 1903, Page 185, Accessed September 3, 2017. https://archive.org/details/lettersdiaryofjo00rowe

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

Read Part 1 and Part 2! This is the final part in a 3 part post.

On Portraying a Member of the Religious Society of Friends During the American Revolution

My personal re-enacting story is not unlike many, I have always loved history! From an early age, in fact as far back as I can recall my family were taking vacations that always included an historic site in our plans. My mother tells the story that we would visit these places and I would have so many questions but when she didn’t have an answer I would get upset. She soon resorted to purchasing a guide book at every site we would visit. My first taste of the 18th century was Colonial Williamsburg, as time passed my obsession with history was fueled by my family who would buy me books for every occasion, mostly Civil War at this time. The 18th century interest came after seeing the film Last of the Mohicans (I know but we all had to start somewhere) and instantly knew I had to get into the re-enacting somehow… but that would have to wait.

After my Bachelor’s Degree then Graduate School I finally was at a point that I could think about a hobby. The next several years I participated as much as I could attending events with the Maryland Forces, the 3rd Battalion Pennsylvania Provincial Regiment or Augusta Regiment, then Muskets of the Crown, which was my gateway into the Revolutionary War. Then came the ultimate opportunity, at least for me at that time, I met the Augusta Co. Militia, my re-enacting family and friends for life. I fell in with the ACM after being invited to attend an immersion event at Fort Frederick MD. I finally felt like I “fit”! This group of likeminded people with a laser like focus on accuracy, research and authenticity were just the group I was looking for. I have mostly moved my impression(s) away from the military life and more towards the civilian side of things, however I occasionally field with the ACM for militia company or rifle company events but for the most part my uniforms are retired, replaced by civilian clothing.

[gallery ids="3126,3127" columns="2" size="medium"]

So, with that said when, where, and why the Quaker impression? It goes back to an event at Monmouth Battlefield where I knew I could not march nor did I have military gear correct for the impression, so civilian it was and lucky for me there was a need for civilians. There were several impressions available and I chose a New Jersey slave owner so my good friend Anna Gruber-Keifer would have someone to play off her Quaker impression with. It was a good thinking moment and I began to research the Quakers (opens HUGE can of worms) …

The next event was the “With Peal to Princeton” march and again the civilian contingent came out but accompanied with that was the AMAZING opportunity to be involved with a promotional shoot for the Museum of the American Revolution. I was asked if I could portray a Quaker, I said yes and knew to do it right I would have to do my homework. I as many had the vision of the Quaker Oats Man in my head as the essential costume of a colonial Quaker. Well I needed to start digging for a better basis than that.

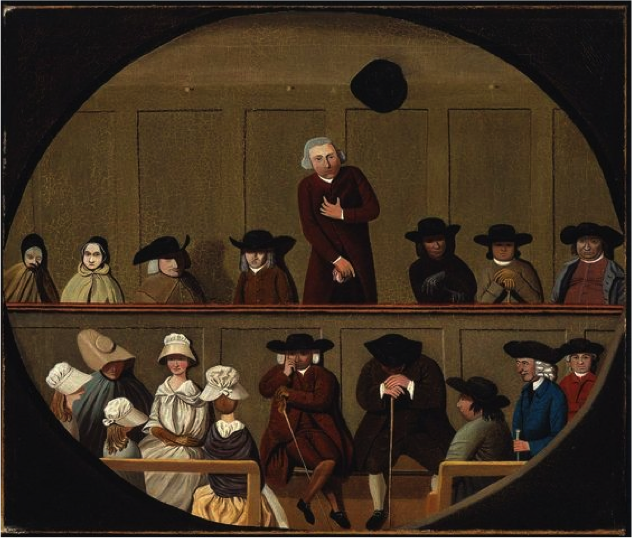

One of the few images available for Quakers of the time is found in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, by an Unidentified Artist. It depicts a Quaker Meeting with what appears one individual standing to give a Testimony. Here was my start, the “plain” attire consistent with the Testimony of Simplicity showed that my brown coat and black waistcoat could work. I would need to construct some breeches for the shoot. Additional research on Quaker dress of the period soon enlightened me further. Although plain dress alone does not make one a Quaker, it was simply an outward expression of faith and adherence to the tenants of the faith.

So profound was the dress that several 18th century authors made mention of it. One example comes from John Wesley (1703-1791) in The Sermons of John Wesley, Sermon 88, On Dress when he encourages his congregation to dress like the Quakers:

So profound was the dress that several 18th century authors made mention of it. One example comes from John Wesley (1703-1791) in The Sermons of John Wesley, Sermon 88, On Dress when he encourages his congregation to dress like the Quakers:

"I conjure you all who have any regard for me, show me before I go hence, that I have not laboured, even in this respect, in vain, for near half a century. Let me see, before I die, a Methodist congregation, full as plain dressed as a Quaker congregation. Only be more consistent with yourselves. Let your dress be cheap as well as plain; otherwise you do but trifle with God, and me, and your own souls. I pray, let there be no costly silks among you, how grave soever they may be. Let there be no Quaker-linen, -- proverbially so called, for their exquisite fineness; no Brussels lace, no elephantine hats or bonnets, -- those scandals of female modesty. Be all of a piece, dressed from head to foot as persons professing godliness; professing to do everything, small and great, with the single view of pleasing God"

(emphasis mine)

In his text “Letters From An American Farmer”, J. Hector St. John De Crevecoeur (1735-1813) writes:

The manners of the Friends are entirely founded on that simplicity which is their boast, and their most distinguished characteristic; and those manners have acquired the authority of laws. Here they are strongly attached to plainness of dress, as well as to that of language;

Additionally I found this description of Quakers from Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) In his book “A Portraiture of Quakerism, Volume 2 published in 1806.

"Peculiar Customs" begins with dress.

"The dress of the Quakers is the first custom of this nature, that I purpose to notice. They stand distinguished by means of it from all other religious bodies. . . . Both sexes are also particular in the choice of the colour of their clothes. All gay colours such as red, blue, green, and yellow, are exploded. Dressing in this manner, a Quaker is known by his apparel through the whole kingdom. This is not the case with any other individuals of the island, except the clergy . . ."

The Quaker impression went over well at Princeton, and the photos were used in a promotional campaign for the new museum. At Princeton, we had some great crowd interaction on the streets and even had the headmistress of the Friends School adjacent to the battlefield come up and engage me and others in some very meaningful conversation. With fuel for the fire I began reading more and researching the Quaker belief system, its origins, its impact on the Revolution etc.

To talk about all aspects of the Quaker religion, its impact on the social and political environment of the American Revolution is well beyond the scope of this post or my limited knowledge. I have, however over the past year begun to dig more deeply, not only on the Quaker faith but its history and impact on history. Some notable Quakers from this period were Thomas Paine author of Common Sense and American General Nathanael Greene. There are examples of Quakers participating on both sides of the conflict. As well as Quaker persecution by both sides. The most common reference to this I have found so far was regarding the “taking of oaths” which is against Quaker teachings. This led many in the faith to be branded as Loyalists and vice versa. I believe this is a good example of the difficulties many Quakers may have faced in keeping strong in faith while living in a “world turned upside down”. Recollections of the war were recorded by the likes of Phebe Mendenhall Thomas, Joseph Townsend, and Daniel Byrnes all of whom were present at the battle of Brandywine. Their stories shed some light into the thoughts and feelings of Quakers before during and after the battle.

I have always been fascinated by religion from an historical perspective so digging into the Quaker belief system was only natural for me. Although not a practicing Quaker in any stretch of the imagination, the idea of attending meeting now and again if for nothing else but to sit quietly and reflect seems a very inviting opportunity. I'll report back if there is interest in my experience.

There are always common questions from the public that arise when I put on my “Quaker” kit. I get a lot of “who are you?” or “what are you doing here?” this one is especially true when at military specific re-enactments. Through trial and error, I have learned it is a good idea if one is going to represent a religion or its members, you had better know as much as you can about that religion. This is one aspect of portraying a Quaker that is an even bigger challenge for reenacting and public interactions. Here in Pennsylvania I have noticed that more often than not, you will come in contact with someone who is either a Quaker or has been exposed to the Quaker religion via a friends’ school etc. So, knowing what you are talking about IS VERY IMPORTANT.

One of the most common question that came up on a trip to the Museum of the American Revolution opening weekend was; “are you Ben Franklin?” As I don’t think myself looking much like this founding father except my generous size, I would explain “no I am portraying a member of the Religious Society of Friends or a Quaker”. Many times, this would be the end of the conversation, but I try to engage the public whenever possible throwing out the bait as to just how did the revolution impact this social, religious and political group of people and vice versa. The individual stories aside, one of the primary areas of conversation I try to engage the public in is the idea of being true to one's beliefs in a world of political change and upheaval? To me this presents a huge talking point and draws some direct relationships between the world of Revolutionary America and the America we are experiencing today.

I take re-enacting not so much as a hobby to be enjoyed on the weekends but more of a calling. I put time and effort not only into my clothing, and elements of material culture, but into my interpretation to the public. I try NOT to perpetuate falsehoods or keep the stereotypes going. I am always trying to learn, expand my knowledge and engage people in the subject I have such passion about. I know I am no expert, I am no classically trained historian I am an amateur at best but I respect the people, places, and things that constitute our collective narrative and strive to present that to those who are willing to listen.

BRANDYN CHARLTONBrandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 21 years working in the clinical, high school, and collegiate practice settings.

BRANDYN CHARLTONBrandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 21 years working in the clinical, high school, and collegiate practice settings.

He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area.

Laundry Methods During the American Revolution: The Really, Really Quick Version

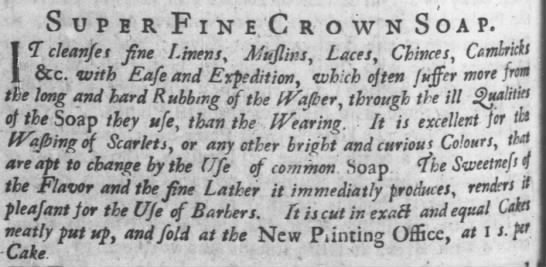

There are several guides to washing laundry in the 18th century—some are quite detailed, while others are fantastically vague (“enough indigo to make the water sky blue”). What follows is a quick compilation of several of those guides, various civilian and military notations about laundering in the American colonies, plus a few personal observations.

Laundering an article of clothing was often done through the same process as finishing a newly-woven textile. The process usually began with a soaking of some sort. One method of soaking was to use a hot or cold lye. This soaking process was usually referred to as “bucking,” and some households had a specific bucking tub or basket. Bucking served to break down grease, loosen dirt, and whiten yellowed linen. The items to be laundered were placed in the bottom of the tub, and a piece of cheesecloth was placed over the top of the tub. Ashes were then placed on top of the cloth, and hot water was poured atop the ashes. The lye was collected, then reheated, and poured through again. Chamber lye was also used for bucking—as well as for removing lanolin from wool and setting dyes. Hannah Woolley notes in The Complete Servant Maid (1677): “Before that you suffer it [linen cloth] to be washed, lay it all night in urine, the next day rub all the spots in the urine as if you were washing in water; then lay it in more urine another night and then rub it again, and so do till you find they [ink stains] be quite out.” [1] As this is an extended process, it’s not always a part of the wash cycle, but a part of what Hannah Glasse refers to as a “great wash.”[2]

Once the soaking process was complete, soap was then applied to dirty spots and rubbed between the hands. There is absolutely no evidence of rub boards, scrub sticks, or washboards in inventories, instructions, or images. Experimental archaeology has shown two things: rubbing the item between the hands with soap or scrubbing the item along the inside of the bucking tub removes dirt and stains fairly well. Occasionally, a laundress will be instructed to use a brush to work in a stain remover such as lemon juice or vinegar, but that appears to be referencing stains on woolens, fine linens, cottons, or silk. Laundry bats and possers may also be used to squeeze water and soap (sometimes not soap) through clothing in order to clean it. In some locations, laundry would have been trampled with the laundress’s feet, as shown in the famous (infamous) image of the Scots washerwoman. A letter from Edward Burt, an Englishman traveling in northern Scotland in 1754 observed:

“... commonly to be seen by the sides of the river ... in all the parts of Scotland where I have been ...women with their coats [petticoats] tucked up, stamping, in tubs, upon linen by way of washing ….” [3]

Occasionally, laundry was boiled BEFORE soaping, as John Harrower described to his wife:

“They wash here the whitest that I have ever seed for they first Boyle all the Cloaths with soap, and then wash them, and I may put on clean linen every day if I please….” [4]

Most sources, however, note that hot water sets the stains and the clothes should be boiled after rubbing. Janet Schaw, an Englishwoman, observed laundry being done in Wilmington, NC in 1776. She wrote that

“all the cloaths coarse and fine, bed and table linen, lawns, cambricks and muslins, chints, checks, all are promiscuously thrown into a copper with a quantity of water and a large piece of soap. This is set a boiling, while a Negro wench turns them over with a stick.” [5]

From this, we can infer that most laundry would have been separated before boiling.

Schaw also had much to say about the rest of the laundry process:

This operation [boiling] over, they are taken out, squeezed, and thrown over the Pales to dry. They use no calendar; they are however much better smoothed when washed. Mrs Miller showed them [how to wash linen] by bleaching those of Miss Rutherfurd, my brother and mine, how different a little labour made them appear, and indeed the power of the sun was extremely apparent in the immediate recovery of some bed and table-linen, that has been so ruined by sea-water that I thought them irrecoverably lost. [6]

Schaw also noted that North Carolinians were the “worst washers of linen I ever saw, and tho’ it be the country of indigo, they never use blue, nor allow the sun to look at them.” [7] Indigo was used as a bluing agent— an optic brightener—and was added to the final rinse. It is unclear as to how much indigo was actually used; a few guidebooks note that enough indigo should be added to “make the water sky-blue.” Most bluing references in America are to fig blue or fig indigo, was probably a lesser grade of indigo. As indigo was a cash crop of Carolina, it was readily available in the American colonies. Stone blue is another term seen on occasion.

Blue could be added to starch, as noted in Amelia Chambers’s The Ladies’ Best Companion:

Moisten the quantity of starch you want to use, according to the quantity of your cloaths, with water, and put as much stone blue as is necessary. When the starch and blue are properly mixed, then let the whole boil together a quarter of an hour longer, taking care to keep stirring it, because that makes it much stiffer and is better for the linen. Such things as you would have most stiff, ought to be put first into the water, and you may weaken the starch by pouring a little water upon it. Starch ought to be boiled in a copper vessel, because it requires much boiling, and tin is apt to make it burn. Some people mix their starch with allom, or gum arabic, nothing is so good as isinglass, and an ounce of it is sufficient to a quarter of the pound. [8]

Starch receipts from the period used a variety of items: potatoes, rice, wheat, even horse chestnuts (patented in 1796 to Lord William Murray).

Once the rinsing and bluing was complete, the laundry was then dried. Period images show laundresses drying laundry in any open space: on wash-lines (usually made from linen or hemp rope), across tents, hung on fences and bushes, and even laid out in the grass. The sun acted as a bleaching agent. (See above for Ms. Schaw’s comment on the sun.) Once the laundry was dry, the laundress then faced the task of ironing or smoothing the linen. Those items that needed ironing needed to be re-dampened and then were placed on a table with a cloth above and beneath (there are a few images of camp laundry being smoothed on the ground). Then a wooden roller or heated iron was passed over the damp linen, stretching and smoothing the article of clothing.

There appears to have been much variation in the quality of the washing done in America. While linen was the predominant fabric being washed, laundresses were also tasked with cleaning dyed and/or printed linens and cottons, woolens, and silk. These materials could, indeed, be cleaned, but often required much more time and effort in their care. As such, outer garment were not washed as often as undergarments, but they were most definitely cleaned.

Footnotes:

[1] Hannah Woolley, The compleat servant-maid; or, The young maidens tutor Directing them how they may fit, and qualifie themselves for any of these employments. Viz. Waiting woman, house-keeper, chamber-maid, cook-maid, under cook-maid, nursery-maid, dairy-maid, laundry-maid, house-maid, scullery-maid. Composed for the great benefit and advantage of all young maidens. (London: printed for T. Passinger, at the Three Bibles on London Bridge, 1677), 69. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A66839.0001.001/1:7?rgn=div1;view=toc[2] Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy: Which Far Exceeds Any Thing of the Kind Yet Published, (London: W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton, et al, 1774), 330.[3] Edward Burt, Letters from a gentleman in the North of Scotland to his friend in London ... likewise an account of the Highlands with the customs and manners of the Highlanders, (London: Ogle, 1822).[4] John Harrower, “Diary of John Harrower, 1773-1776,” American Historical Review 6, no. 1 (1900), 84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1834690.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A67f1d3a92c1ae1a426a54ea7c55502c0[5] Janet Schaw, Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776, eds, Evangeline Walker Andrews and Charles McLean Andrews, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 204.[6] Ibid., 206.[7] Ibid., 206.[8] Amelia Chambers, The ladies best companion; or, a golden treasure for the fair sex. Containing the whole arts of cookery ... With plain instructions for making English wines ... To which is added The art of preserving beauty, London: Printed for J. Cooke, 1800.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

ANNA ELIZABETH KIEFERis an adjunct professor at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, an independent scholar, and a public historian. She has a B.A. in History from Washington College in Chestertown, MD., and an M.A. in Early American History from the University of New Hampshire.

Her research areas include Germanic settlement and culture in the greater Shenandoah Valley, the material culture of followers of the British Army through the American Revolution, and the Women’s Land Army of America in Virginia and North Carolina during the first World War. She is a founding member of the progressive civilian organization, The Laundry Company. She loves cats, coffee, and puns, and not necessarily in that order.

Disheveled, Poor and Shabby, The Average Soldier’s Wife

The hobby of reenacting as whole has undergone many changes in the past decade. I would say those changes were made in leaps and bounds towards outstanding impressions done by women in the hobby. We have had some excellent patterns become commercially available based on extant garments for the female living historian. (I’m looking at you Larkin and Smith. Thank you!) The digitization of museum collections and the sharing of those images on social media on sites such as Pinterest has been invaluable. The social networks have transformed our small and often insular community. We now have the ability to connect to one another in ways we never could have imagined. We can share images of our impressions with the world with a small very powerful computer we carry in our pocket. It takes but a second to have your new kit be the all the rage on various pages. Your image may be shared, liked, tweeted and loved. This past spring an event, attended by the 17th, at Short Hills produced some images that were happily shared on my wall. One in particular was of some friends of mine standing around a wash tub doing laundry in their stays and petticoats. It is an image that instantly sparked not only admiration for anyone doing laundry at an event but also a sense of recognition that I have seen so many images of working women wearing just such clothing while doing hard laborious work.

The ability to properly portray Soldier’s Wives as they truly were is really not as difficult as some would have you believe. This is due to the fact that so many images exist from the last quarter of the 18th century. It also doesn’t hurt that we have some excellent purveyors of goods and craftspeople reproducing the material culture of that era, as well. We also mustn’t forget the excellent scholarly works that look into the common person’s clothing such as Dress of the People by John Styles or Wives, Slaves and Servant Girls by Don Hagist. These excellent books delve deeply into the subject and I highly recommend reading both of these publications to get a greater idea of the fabrics worn and the vernacular used in the period. Such wonderful terms such as Stuff, referring to worsted, Cassimere, referring to tropical weight worsted, Harebine, a wool silk blend that is slightly fuzzy on one side yet smooth and taffeta like on the other, Cherry Derry, a cotton silk blend that shows up repeatedly in merchant’s advertisements.

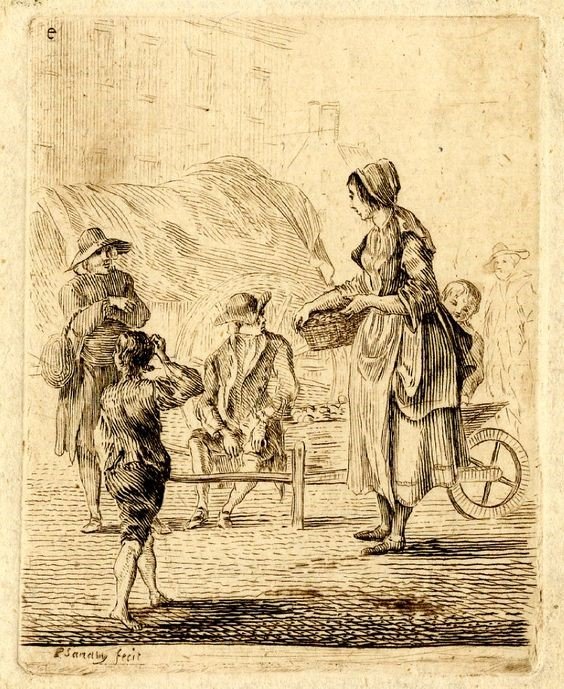

I’ve decided to focus in on the visuals that I referred to earlier. In particular I have chosen a few images rendered by Paul Sandby that very aptly show the look of the common working woman. He focused most of his career painting landscapes, encampments and those living in some of the poorest areas of cities around the UK. He was prolific in his craft and gives us an excellent view of what he saw on a daily basis. The last quarter of the 18th Century was a time almost devoid of social welfare even if it was the “Age of Enlightenment”. These individuals lived in circumstances that would still be recognizable in the third world today. That is what it meant to be the poor working class in a major city in George III’s Britain at the time. He painted them as they were, disheveled, poor, shabby, and most of all, very human. This is the same exact social class of the Private Soldier’s wife which made up over 95% of all Followers of the British Army that we represent. The images I have chosen are from the 1750’s-1790’s as working women’s clothing often were not quite as fashionable or are hard to discern cut due to their ragged condition in the images. The second hand clothing trade kept some pieces of clothing in circulation far beyond the time that a fashionable woman would have worn them.

These women appear to be washing indoors. You should notice that both women are in their shift sleeves, stays and petticoats. Take note the standing figure is wearing her handkerchief, as well. The Royal Collection.

Perhaps my favorite in the series as it gives a highly detailed image of a woman working. Once again, take note of the shift, ferreted petticoats and stays with a handkerchief. Note the details of her windowpane check work apron, as well as the facing on the hem of her petticoat in plain (linen? Wool?) fabric with a striped petticoat underneath. Her pin cushion hangs from her waist as well. The temporary removal of outer garments seems to have been fairly typical when doing manual, filthy or wet work. It is seen repeatedly in images of women doing laundry and other tasks. The Royal Collection.

This image once again shows a woman removing her outer garments such as a Bedgown or Gown to keep her outer garments free of filth or water. This seems to have been a common occurrence and for the working class something that was done in a public area. She also has her apron on and her handkerchief is worn covering her shoulders and chest. The London Museum.

The next undated Sandby Etching shows the simple Bedgown and Petticoat worn by a working woman. She is also wearing flat shoes which we see in many images of women of this class. As we have a General Order saying that Widows and Children of the Regiment may draw shoes and Hose form the company stores, flat shoes can be a valuable interpretive tool. You can see the wheelbarrow behind her which should be of much interest to those who do a laundry or Petty Sutler Impression. Note the bare feet on the young boy scratching his head. The British Museum.

Last Dying Speech and Confession, 1759, from the Twelve Cries of London Series. This

woman has to be the shabbiest of all of the women pictured here. You will notice her Bedgown, Petticoat and Flat Shoes. Please note she is not giving her dying speech she is selling copies of an executed person’s confession at the gallows, which you can see faintly behind her with a crowd around it. Nothing like a day’s entertainment.

Mackerel Seller, 1768. Lastly, this woman with her hand in her pocket, her blue pinner apron to keep the fish oil off her, scarlet cloak and aggressive expression is a personal favorite. She looks very much like many of us do after a weekend in the field hence this is a very achievable look. The surprising lack of gowns in these images is a bit startling but these seem to be the predominant theme in working women’s garments painted by Sandby. National Galleries of Scotland.

This is but a small sampling of images that are available in digital archives most of which are free or have very little cost in acquiring images. The great hope is that you will investigate these terrific images for yourself, study the details, look at the surroundings and add these small details to your impression. It’s easy to be guided by others impressions but the guidance we should be taking is from period images. I chose these images because they illustrate what a soldier’s wife may have looked like after a while on active campaign. We know they are described as a rather ramshackle lot by the locals when the Convention Army passed through New England. Perhaps we’ll see some more working class clothing at events soon.

* Please note second in series is how Sandby numbered this image. It is the first shown in this post.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

The Things We Carry: On the Strength of the Army

A couple weeks ago we had a member of the 17th Regiment of Infantry, Damian Niescior, write about all the things he carried during a weekend in the 18th century as a soldier in the British Army... this week we have a follow up post brought to you by Carrie Fellows, who has been working and recreating 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years. A year or so ago Carrie did a symposium with Kimberly Boice's: Historie Academie, which I happened to attend where she did a talk and workshop on how to pack for an event. So upon request it reminded me that she'd be the perfect fit to talk about what a follower of the army would bring with them.

Read Damian's blog post here.

- Mary S. an attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry

It can be difficult to explain to people what I do for fun. I combine my passion for history and the outdoors by interpreting the lives of women who, out of necessity, followed the Continental Army (and occasionally, the British army) during the American War for Independence. I have portrayed a laundress, an officer’s servant, a refugee, and a soldier’s wife, but regardless of whom I portray, the things I carry with me may vary slightly according to season, but remain essentially the same. Over the years, I have refined and limited the number of objects I carry, lightening my load for travel on foot over long distances, rough terrain, and the occasional river ford.

Records of what women carried are practically nonexistent, but one can find clues in runaway ads, military records, and the occasional primary source. Women attached to the army had only what they brought away with them, or acquired on the road. Women “on the strength” of the army were entitled to a half-ration of food (children received a one-quarter ration.) I am always hungry, and as rations aren’t always available, carry enough food to get by.

Tied about my middle, under my gown, a pair of pockets (1) is suspended. These contain both modern items (pocket on right) and period ones (pocket on left). I often leave my phone in the car unless I need to take photos for a talk or article, or will be in the deep backcountry.* My car keys (40) are pinned firmly to the inside bottom corner of my left pocket. In my right pocket: a sewing kit (2) or “housewife” – a roll of cloth with pockets to hold sewing supplies and tiny items like sleeve buttons, also a linen handkerchief (3), pocket knife (4), linen or woolen mitts (5), period scrip and real cash in a reproduction pocketbook (6), lip balm in a tin container (7).

I carry most of my gear in a wallet (8) – a rectangular cloth bag with a slit opening in the center. One places items in each end, then twists the entire thing at the center, closing the slit and forming a kind of narrow strap, then slung over the shoulder. I try to segregate the two ends into food/related items and clothing/personal items. The food side holds a small bag of cornmeal or rice (9), cheese wrapped in 2 layers of linen (10 - the inner one dampened with vinegar); a cured sausage wrapped in brown paper (11), a small bag of walnuts (12), bread (13), tea (14), salt (15), seasonal vegetables (16), a spice bag, grater, candle ends and extra corks (17), paper packets of flour and pepper (18), and sometimes I even remember my fire kit: flint, steel, charcloth and tow in a tin box (42). Food-related items include a turned wooden bowl (19), which can serve as both drinking and eating vessel, an eating spoon (20), and a linen towel (21).

In the other end, I carry extra clothing items tied up together in a large kerchief (22): moccasins (23) and a man’s wool cap (24) for sleeping in, stockings (25), neck handkerchief (26), and a small paper notebook (27). Some also carry a clean shift, but I do not, as I am rarely in a situation where there is privacy sufficient change it. Also: a tiny modern first aid kit in a red linen bag (28), personal toiletry items in another small drawstring bag: a tin box with soap and mirror (29), horn comb and bone toothbrush (30), handwoven wash towel (31), spectacles (32), allergy meds &, contact lens case (not pictured). Reenactor etiquette requires one to manage any non-historic personal care out of view as much as possible. Optional items, depending on the planned activity: a small bundle of mending patches and yarn (33), and a darning egg (34) to occupy time and to trade (mending skills have value), a large wooden cooking spoon (35), and a small axe (36). If there’s room, “luxury” items include a ceramic cup (37) and a big linen wallet that doubles as a straw tick (38).

I usually carry just one blanket (with a wool petticoat and cloak inside) rolled up, tied together at the ends to form a “U”, and carried across my body. I put on the wallet first, then the canteen (39) - the wallet cushions the strap - then the rolled blanket over that. The blanket helps keep both wallet and canteen secure, close to my body, and quiet as I walk – or run.

The last thing I pick up is my small iron pot (41), with its sheet iron lid tied on so it doesn’t rattle or become lost. If I have eggs or fruit, I pack it in the pot. It goes to every event with me. I hadn’t thought about it before, but that little pot – representing security, hot food, comfort (and home?) connects me to the women I portray who carried what they most valued when they followed the army.

*Nothing ruins an accurate setting faster than when the smartphones come out and glow blue at night.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

The Malicious, Morose Malady and the Vindictive, Vagrant Vixen: A 17th Regiment Story, Part 2