Officers of the 17th Part Four- Choosing Sides in the American Revolution

This entry will be a bit different, as it will tell the story of three retired officers of the 17th who had sought new lives in America in the 1760s and 70s, only to find themselves caught up in the turmoil of the American Revolution. Faced, like all residents of the American colonies, with difficult questions of loyalty and identity, these three reacted as variously as the broader population. Richard Montgomery, the best known of the three, enthusiastically embraced the Patriot cause and died a hero of the Revolution. James Howetson stayed loyal to his king and died trying to recruit men for a Loyalist unit. The sickly William Howard was a supporter of the Patriot cause married to a Loyalist wife, and sought to achieve domestic harmony by avoiding the subject.

First, some background. With a major commitment of British regulars to North America during the Seven Years War came increased contact between its officers and the colonial world. The elites of the British army tended to mix with colonial counterparts wherever they were stationed, seeking the “society” of polite company among merchants, planters, and professionals. At the most obvious level, dance partners often turned into wives. The correspondence of British officers of the period mentions what General James Murray, writing in 1764 from Montreal, called the “Matrimonial Distemper”, and it is easy to find dozens of examples of officers marrying into the higher reaches of colonial society. Just a few- At the very top is the marriage of General Thomas Gage to Margaret Kemble of New York, while his military secretary, Captain Gabriel Maturin, married into the Livingston family, also of New York. Other examples include Major Pierce Butler of the 29th marrying a daughter of Thomas Middleton, a prominent South Carolinian and Arthur St Clair of the 60th, who married into the Bowdoin family of Boston when stationed there in 1760. (see John Shy, Toward Lexington, pp. 354-358).

A second, and often related, attraction of the colonies was the ready availability of land. Younger sons of the British gentry often sought to improve their economic positions by settling on American estates. Occasionally they were granted land by the government, but more often they were able to purchase estates by selling their commissions and using the proceeds, or by marrying into the prosperous colonial classes. Our first example, Richard Montgomery, did a bit of both.

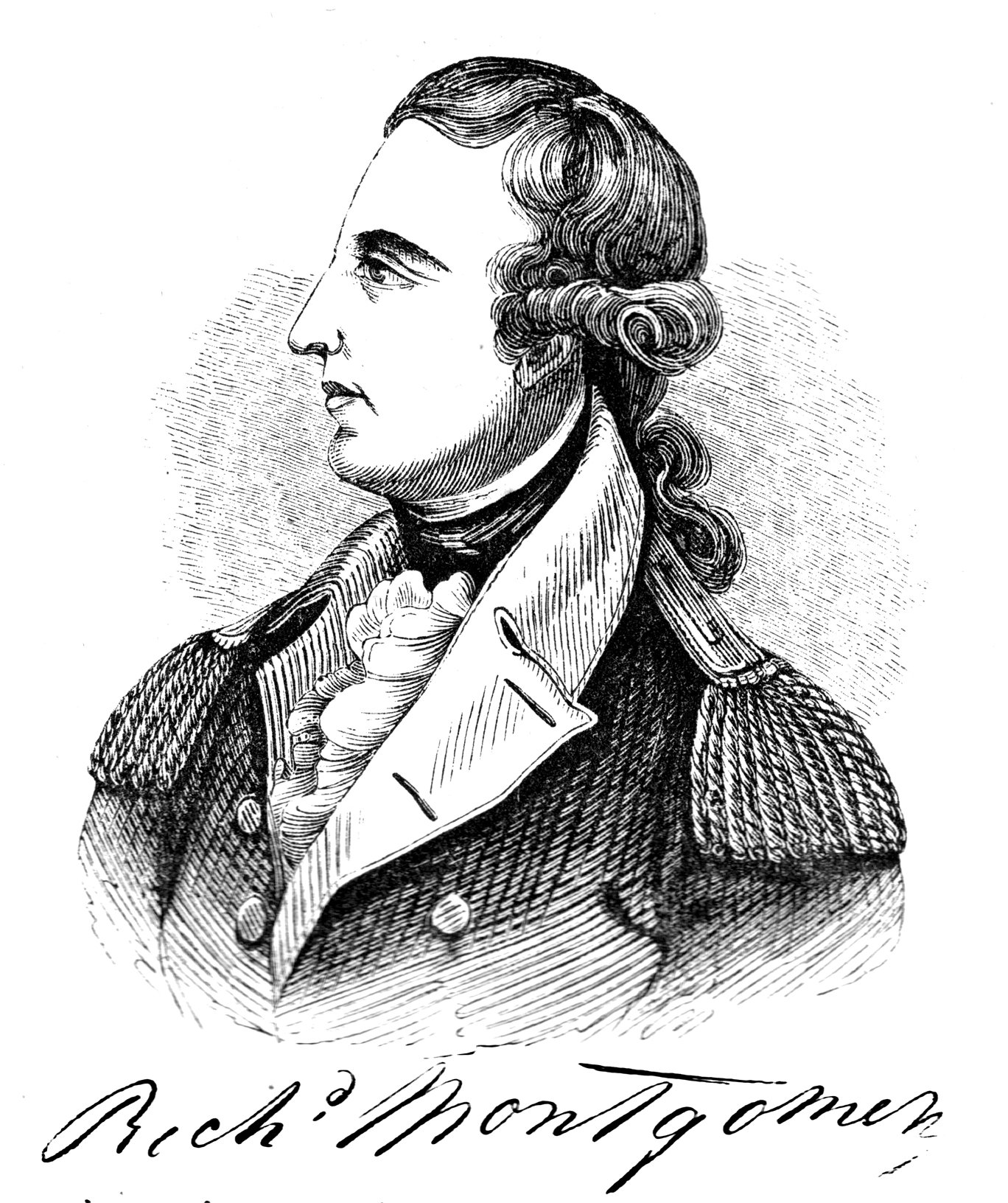

Richard Montgomery was born in 1738 into an Anglo-Irish landed family with a strong military tradition. His grandfather, father and older brother all served as officers in the army. Richard’s father, Thomas Montgomery, was disinherited from the family estate of Ballyleck when he married without permission, but nevertheless served as an MP for Lifford. Richard had a more extended education that most officers of the day, attending Trinity College, Dublin for two years before leaving university to join the 17th regiment. His father purchased his ensigncy for him on April 21, 1756 and Richard sailed to New York with the regiment the following year. He served through the siege of Louisbourg and, when a captain of the regiment was killed by a French sortie, was promoted to lieutenant without purchase on July 10, 1758. The 17th served in the successful siege of Ticonderoga the following year, though it appears to have been a troubled regiment. Personality conflicts among senior officers, abuse of enlisted men by officers and non-coms, desertion and indiscipline adversely affected the 17th’s performance during the early years of its service in America. The regiment began to improve in the later part of 1759 as several officers resigned and more competent ones advanced in rank. It is perhaps a sign of the professional stature of the young Richard Montgomery that he was appointed adjutant on May 15, 1760 on the court martial and dismissal of the previous adjutant. (see BLG of Ireland, 1904, p. 412, Montgomery of Beaulieu; George Montgomery, A History of Montgomery of Ballyleck; and Michael Gabriel, Major General Richard Montgomery, pp. 17-27.)

Following the conquest of French Canada the 17th participated in several grueling campaigns in the West Indies, with severe losses in the unhealthy islands. Montgomery was at the capture of Martinique and Havana, purchasing his company on May 4, 1762. The sickly remnant of the regiment returned to New York in August of that year, and spent nine months recruiting and recovering. Montgomery was among the sick, later recording that the climate of Cuba “made him lose a fine head of hair.” The regiment then served in Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763-4. Montgomery finally returned to Europe on leave after six years of service in America, having campaigned and travelled over much of the middle colonies and Canada and with a wide circle of acquaintances among New York’s elites. (Gabriel, pp. 28-36).

Peacetime soldiering did not agree with Captain Montgomery. Frustrated with repeated unsuccessful attempts to purchase his majority and with few opportunities to excel at his profession, he eventually decided to leave the army. In 1772 he wrote to his cousin “You no doubt will be surprised when I tell you I have taken the resolution of quitting the service and dedicating the rest of my life to husbandry….And as a man with little money cuts but a bad figure in this country among Peers, Nabobs, etc, etc, I have cast my eyes on America, where my pride and poverty will be more at their ease.” Magill Wallace, a fellow officer in the 17th, Montgomery’s close friend, and related to a family of New York merchants, purchased his captaincy for over 1500 pounds. The sale of his commission and his properties in Ireland gave Montgomery the money to get started on his new career in America, and he purchased a farm in Westchester County, New York by the spring of 1773. He married Janet Livingston, a member of one of the most powerful landowning families of New York, in July of that year, thus entering the highest circles of New York provincial society. (Gabriel, pp. 40-59)

As the series of crises leading to the American Revolution forced New Yorkers to take sides, the Livingstons emerged as leaders of the Patriot faction. Richard Montgomery was probably predisposed to sympathize with the Patriot cause, as he was familiar with similar struggles playing out amongst Ireland’s Protestant elites during the same period. Still, it was a gradual process for him. Though his sympathies lay with the Patriots, he also remained attached to his old comrades of the 17th. He continued to correspond with Perkins Magra, writing him in 1774 that he “entertain[ed] a more cordial regard [for the officers of the regiment] than I shall probably ever again feel for any of my fellow creatures.” Initially reluctant to engage in politics, he was selected as a delegate to the provincial congress in May of 1775. When the Continental Congress appointed George Washington as commander of the American army in June and sought out other experienced military men to act as his subordinates, Richard Montgomery was appointed a brigadier general in the new Continental army. (Gabriel, pp. 70-82).

I will give only a brief summary of his career in the American army, as his story is well known and extensively covered elsewhere. Montgomery’s served on the Canadian front, revisiting much of the ground he had campaigned over during his years in the 17th. Serving under Philip Schuyler, he helped organize the northern Continental army and was second in command as it commenced the invasion of Canada. He then commanded the army during the two month siege of St Johns, capturing it on November 3, 1775, then marched into Montreal ten days later. He led his undisciplined, sickly and poorly supplied army on to Quebec City, and died leading it in a desperate assault on the town on December 31st. Richard Montgomery became one of the earliest heroes and martyrs of the American Revolution, and was celebrated in paintings, poetry and plays. (Gabriel, chapters five through eight).

My second subject was far more obscure. James Howetson (also Hewetson, Huston) was born in Scotland circa 1736 and joined the 17th as an ensign without purchase on April 29, 1762. He served in the final campaigns of the war and in Pontiac’s Rebellion and was with the regiment until he retired in 1769. A number of sources describe him as a half pay lieutenant, but I have found no evidence that he was on the half pay list or reached the rank of lieutenant. He settled in New York after leaving the regiment and married Engeltje Wendell in 1772. His wife belonged to a family of German descent long settled around Albany and Schenectady. At the outbreak of the Revolution he was living in Lunenburgh (present day Athens, Greene County, New York). Other sources list him as a resident of nearby Coxsachie. As a former British officer he was suspected of Loyalist sympathies and the Albany committee of safety forced him to sign a parole on April 30, 1775. Howeston promised to stay near his home, talk with no other Loyalists and take no action against the Revolution. He first violated his parole by helping to set up a Loyalist communication network, and received a warning from the committee. He seems to have received several other warnings, including an order to desist in recruiting for Loyalist units.

In late 1776 or early 1777, Howetson was appointed to a secret commission as captain to a loyalist battalion being raised on Livingston Manor by New York Loyalist Sir John Johnson. The large manorial estates of the Livingston family had long been a site of tension between the great proprietors and their tenants. The Livingstons, as mentioned above in Richard Montgomery’s sketch, sided with the Patriot cause, and their dissatisfied tenants tended to side with the British, hoping a Loyalist victory would lead to land reform and better economic conditions. Howetson and other Loyalists and former British officers attempted to raise a Loyalist unit among the tenants of Livingston Manor. In May of 1777 some five hundred of them gathered, hoping to join the British forces advancing from Canada. Patriot militia reacted promptly and crushed them at a skirmish known as the “Battle of Jurry Wheelers” on May 2. Many were jailed for a time, and two, including Howetson, were sentenced to death. Howetson was charged with treason for recruiting for the enemy while a citizen of New York. He seems to have been regarded as a man who was particularly culpable as he had violated his parole several times, and had been warned to cease recruiting. His court-martial, held on June 14, 1777, sentenced him to be hanged. He was executed at Albany either on July 4 or sometime in August. (see Harry Ward, The War for Independence and the Transformation of American Society (1999), p. 43; Philip Ranlet, The New York Loyalists (1986) pp. 130-2; Loyalist Trails UELAC Newsletter, 2005, biographical sketch by Gavin Watt; New York Marriages; Schenectady Digital History Archive, Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs: Wendell).

Our third officer sided with the Revolution but seems to have been too decrepit to do much about it. William Howard was born in England circa 1720. Some family historians have attempted to link him with the great northern landowners of Yorkshire and Cumbria, the Howards, Earls of Carlisle, but there is no real evidence about his family background. He was commissioned as an ensign in the 17th on July 5, 1735, became a lieutenant on April 25, 1741, became adjutant to the regiment in 1746, became a captain lieutenant on April 17, 1756 and purchased his captaincy on Nov. 22 of that year. Howard travelled to America with his regiment and served throughout the Seven Years War. One of the few glimpses of him on campaign that I have found occurred while he was part of the force besieging Fort Ticonderoga in July of 1759. On the night of July 26 the French garrison withdrew from the fort and attempted to destroy it by blowing up the powder magazine. The explosion resulted in a shower of rocks on parts of the British line and several companies of the 17th panicked and abandoned their posts. Several officers were court-martialed over the incident, including Captain William Howard. He was able to establish that he did his utmost to rally his men and bring them back to the line in good order, and was exonerated by the court. (WO71: 67, Court Martial of Captain William Howard, 30 July 1759).

![]()

The first hint of his interest in settling in America comes when the regiment was stationed in New York in September of 1763, when Howard requested leave “to go down to the Jersies on leave, his concerns…require his presence.” (WO34:53, f. 128 Campbell to Amherst Sept. 30, 1763). In June of 1767, on the eve of the regiment’s return to England, he applied to General Gage for permission to sell out, as his state of health no longer permitted him to go on active service. (Gage Papers, Clements Library, Gage to Howard June 27, 1767). He settled near Princeton in a house known as Castle Howard (thus abetting the confusion about his unlikely origins as a member of the British aristocracy), with 200 acres of land and some woodland. According to a post-Revolutionary War affidavit prepared by President Witherspoon of Princeton College, Captain Howard “lived in a genteel manner” and “was generally believed to be wealthy.” He married Sarah Hazard, most likely related to a merchant family with interests in New York and Philadelphia. (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, Vol. 9, p. 85 biography of Ibbetson Hamer; Recollections of Olden Times: Genealogies of the Robinson, Hazard and Sweet Families of Rhode Island, p.260)

Howard played a very small role in the Revolutionary crisis, though his views were well known to locals. According to tradition, he was a victim to gout and was confined to his room by 1776. While he was an ardent Patriot, his wife was an enthusiastic Loyalist, and insisted on entertaining British officers who passed through the community. The old veteran, forced to listen to their unwelcome political views, had painted over his mantel “No Tory Talk Here”. He died some time in 1776, and his wife promptly married another British officer, Ibbetson Hamer of the 7th Foot. Her property was confiscated in 1777 and she removed to England with her husband after the war. (above, and PCC Will of Sarah Hamer, November, 1821)

None of these three former officers survived the war. Montgomery sided with the Patriots, died in battle and is remembered as a hero of the Revolution. Howetson continued to serve his king, ignored repeated warnings to cease recruiting, and was hanged, a near forgotten victim of what was, in many respects, a civil war. Howard paid, perhaps, the smallest price, with the peace of his final years disturbed by trouble in his household.

DR. MARK ODINTZ PhD.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

DR. MARK ODINTZ PhD.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

Did you miss the beginning of this discussion? Find parts 1, 2, & 3! Linked there.