Three Captains of the 17th

Mark Odintz returns to the blog this week to reveal the stories of three key officers who served in the 17th during the American Revolution. Their experiences reveal the different paths that officers took in joining the regiment and the varieties of experiences that holders of the king's commission could expect to confront during their careers. As always, we appreciate Mark sharing his wealth of knowledge.

- Will Tatum

For my next installment of the officers of the 17th, I want to take a look at three long service captains of the regiment, Francis Tew, William Scott and William John Darby, men who spent most of their time in the service in the 17th. Darby and Tew’s ties to the regiment go back to the Seven Years War and all three were mainstays of the regiment for much of the American Revolution.

Francis Tew, one of the bravest and most stalwart (if also one of the unluckiest) officers of the 17th, was born in Ireland in 1737, the child of William Tew of Roddinstown, county Meath, and Hester McManus Tew of Maynooth. He came from the marginal edges of the landed gentry. His father was a third son, and had a large family. Francis’s eldest brother, Mark of Roddinstown, who inherited what property there was, attended Trinity College, Dublin and was described as a “farmer in County Meath”. (National Library of Ireland, Pedigree of Tew Family; plus notes on Tew family on Bomford.net).

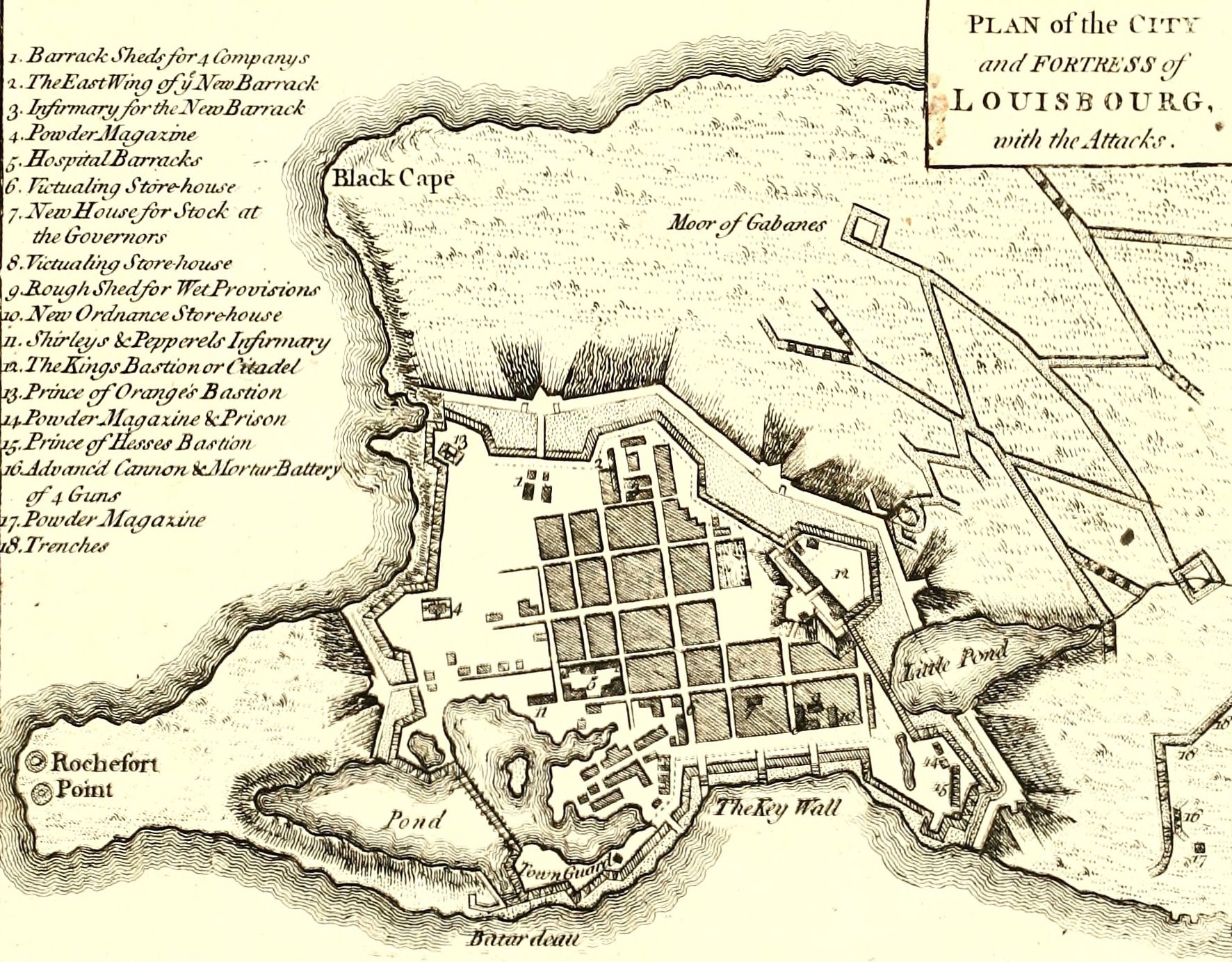

Tew’s early career benefited from the expansion of the British army at the opening stages of the Seven Years War. He entered the 17th as an ensign, most likely without purchase, on April 27, 1756, and was promoted to lieutenant, also without purchase, on Feb. 2, 1757. He served in the grenadier company at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758, and was caught up in one of the few setbacks suffered by British arms during that well-conducted siege. On the night of July 9th the French garrison sortied against the post held by the grenadier company of the 17th and achieved a complete surprise. The company commander, Captain William, Earl of Dundonald, was killed, and Lieutenant Tew was wounded and captured. According to his own memorial of 1770 he “recd 7 Musket Balls in different parts of his body” and his wounds are described in more excruciating detail in Roger Lambs “Journal of the American War”. According to Lamb his wounds appeared so serious that he was not treated for three days, “the surgeons expecting his death every half hour.” He eventually recovered, and rejoined the regiment for the West Indian campaigns at Martinique and Havana. (Lamb, p. 274-75; Barrington Papers, 6D/379, memorial of Francis Tew, 1770 or 1771).

In a rather striking example of how officers without money to purchase could endure wounds and long service and still be stuck in the junior ranks of the officer corps, Tew was still a lieutenant when the regiment returned to England at the end of the war. When the 17th was reviewed at Kew in 1768 General Lord Amherst paid particular attention to Tew “on account of his great sufferings at Louisbourgh”, and, if Lamb’s account is to be believed, the King noticed him as well “and after conversing with him very familiarly for some time, put his name down in his memorandum book, in order that he might not forget him when an occasion for promoting him should occur.” (Lamb, p. 275; WO 34: 157, f. 190, Memorial of Rose, Eleanor, and Hester Tew, Oct 12, 1779) Whoever talked to him at the review, Francis had to wait two more years before purchasing “with difficulty” the captain lieutenantcy of the 17th on Aug. 6, 1770. He was promoted to captain without purchase on the death of Captain Hope on Nov. 14, 1771.

Tew came back to America with the 17th to fight in the Revolution, and as the most senior captain was frequently in command of the regiment while it was in the field. At Princeton the lieutenant colonel, Charles Mawhood, was detached as commander of the entire British force and the major, Turner Straubenzee, was off commanding a battalion of light infantry. The following year, at Germantown, both field officers were absent once again, and Tew led the regiment through that battle as well. His final action was at Stony Point in 1779. On the night of the surprise attack Captain Tew, acting commander of the regiment (since Lt. Col. Johnston was in command of the entire garrison) was stationed at one of the forward posts. According to the account of Lieutenant John Ross, while attempting to rally his men Tew was confronted by “a body of rebels…who desired them to surrender on which Captain Tew made use of some hasty expression, which the witness does not remember but Capt Tew was immediately fired on and killed.”. It seems fitting that the old soldier was shot down while raging at the enemy. Roger Lamb eulogized him in his history of the war, saying that “his loss was at the time sensibly felt through the army.” (WO71:93, Court martial of Henry Johnson; Lamb p. 274).

There is no evidence that Francis Tew ever married. In October of 1779 and April of 1780 Rose, Eleanor and Hester Tew, the spinster sisters of Francis, sent a series of memorials to government figures petitioning for relief, “our former distresses having been grievously augmented by the loss of our most kind and lamented brother.” They were placed on the compassionate list, at 10 pounds a year each. (WO34:157, F. 190, Rose, Eleanor and Hester Tew to Amherst, Oct. 12, 1779; WO1:1006, f. 681, Same to Jenkinson, April 7, 1780; WO34:161, f. 534, Jenkinson to Amherst, Mar. 30, 1780).

Our next officer, William Scott, like Tew and Brereton, particularly distinguished himself during the American Revolution. Like Tew he also seems to have come from the edges of middle class society, though there was evidently ample funding for his military career. His father Benjamin Scott of Osborn near Cranbrook, Kent, was deputy collector of the custom house at the port of London, working under Edward Louisa Mann of the influential Mann family of Linton. William Scott was born c. 1752 and entered the 17th as an ensign by purchase on Jan. 15, 1770. With funds in hand he was able to take advantage of the fact that a number of veterans of the Seven Years War wanted to retire in the 1770s, purchasing his lieutenantcy on Sept. 23, 1772 and his captaincy on August 23, 1775. He purchased his company from Richard Aylmer, who, as his family later complained, had “purchased all his commissions at a very dear rate, so much so, that his company cost him 2000 guineas.” (WO25:3090, memorial of Eliza Aylmer, 10 March 1821.) Most likely Scott was forced to match that sum.

Scott served as a company commander during the early years of the Revolution, first as captain of a line company, then as captain of the light infantry company. At the battle of Princeton in January of 1777 Scott particularly distinguished himself. According to the diary of Thomas Sullivan of the 49th Foot: “Captain Scott of the 17th Regiment with a party of 40 men under his command, having the Guard of the 4th Brigade’s Baggage, was attacked by a large body of the Enemy that were retreating from Princetown; but he formed his men upon commanding ground, and after refusing to deliver the Baggage, fought with his men back to back; and forced the Enemy to withdraw, bringing off the Baggage safe to Brunswick.” General Howe, while commending the role played by the 17th as a whole in the battle, particularly singled out Scott

“for his remarkable good conduct in protecting and securing the Baggage of the 4th Brigade…”

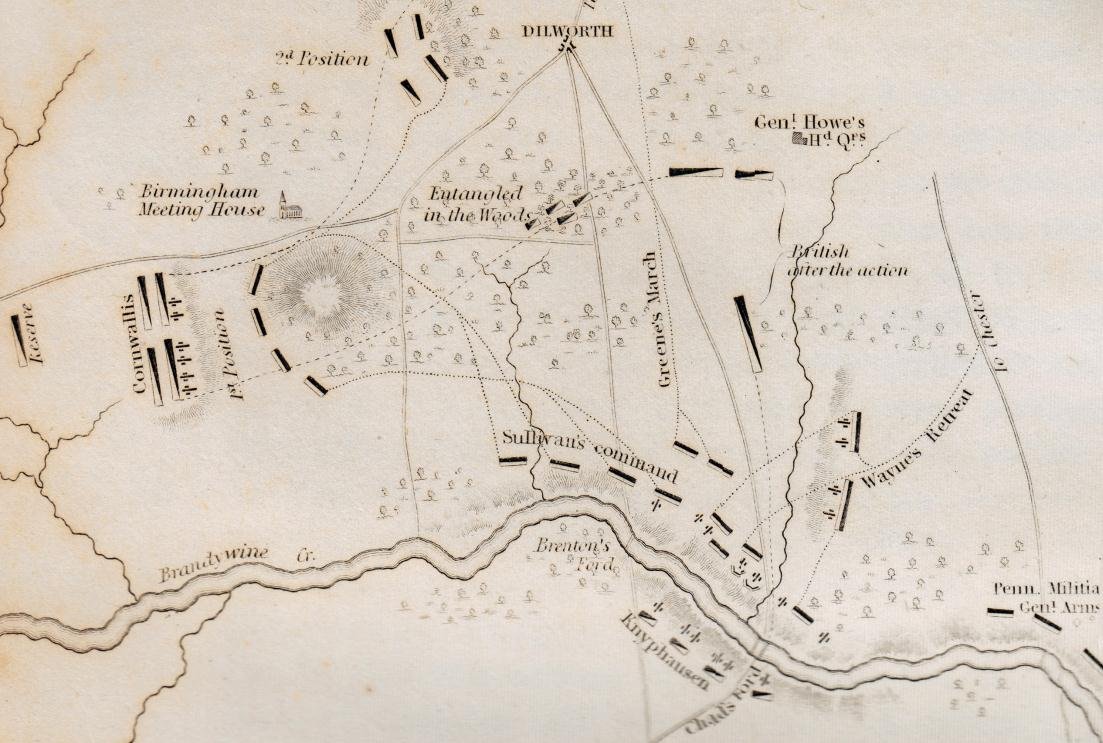

A few months late he replaced William John Darby as captain of the light infantry company, and commanded it during the Philadelphia campaign. He is believed to have been the author of one of the most detailed and vivid accounts of light infantry tactics to survive from the war. At the battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, Scott led his company in an attack on Birmingham Meetinghouse and several enemy cannons firing on them from a nearby hill. “The church yard wall being opposite the 17th light company, the captain determined to get over the fence and into the road; and calling to the men to follow…and lodged the men without loss at the foot of the hill on which the guns were firing.” The detailed account then goes on to describe the company using fire, movement and shock as an independent unit, and, more strikingly, cooperating with other individual companies from the light infantry battalion and even calling on the assistance of a neighboring company of grenadiers from a different battalion. This is far from the stereotype of inflexible battalions maneuvering about the battlefield, and demonstrates the level of leadership and tactical judgement required of light infantry captains like Scott. (See Matthew Spring, “With Zeal and with Bayonets Only”, pp. 185-187).

He continued to command the light infantry at Germantown later that year, leaving another detailed account of fighting at the company level. (see Thomas McGuire “The Philadelphia Campaign Vol. II” pp. 291-294). I have been unable to determine if he was present at Monmouth and the raid on Martha’s Vineyard in 1778. Scott was replaced by George Seymour and shifted to a staff position, most likely in the fall of 1779. By November he was serving as brigade major to General Francis Smith’s brigade, forming part of the garrison at New York. (Eyre Coote Orderly books, Clements Library). I believe he remained in New York for the last years of the war. His testimony at a court-martial in 1781 indicates that he had probably been present in the city since 1778 forwarding replacements to the regiment. (WO71:94, Court-martial of William Hudson, August 11, 1781). In July of 1783 he was again in New York, submitting a memorial of his services and complaining that in spite of his service he had failed to receive “the Brevet Rank of Major conferred on others inferior to him in rank.” (Dorchester Papers, f. 10134, William Scott to Carleton, July 3, 1783). He was promoted major without purchase in the 80th foot in September of 1783, and went on the half pay when that regiment was reduced following the peace.

William Scott still had one more service to perform for his country. Years after going on half pay, Scott played a role in the reform of the British army in the 1790s. In the immediate aftermath of the American Revolution, influential figures in the army had turned away from the hard-won lessons of the war, particularly the use of flexible and highly mobile light infantry tactics in broken country, in favor of copying the impressively massive but impractical formations favored by the Prussian army. When the poor performance of the British forces under the Duke of York in the early campaigns of the French Revolutionary wars sparked a renewed interest in the methods practiced by the armies of Howe and Cornwallis in America, experienced officers were called upon to reform the army. As part of this revival a brigade of light infantry, comprised of both regulars and militia, was formed by General Viscount Howe and “were placed under the command of Colonel William Scott, late of the 80th regiment of foot” who led them in maneuvers in the Essex countryside. (For Scott see Thomas Henry Cooper, “A Practical Guide for the Light Infantry Officer”, 1806. P. xiv; for the argument over the tactical legacy of the American Revolution, see Mark Urban, “Fusiliers”, 2007, pp. 301-319.) Though remaining on half pay, he continued to rise in rank by seniority, becoming a lieutenant colonel in 1794, colonel in 1798, major general in 1805 and lieutenant general in 1811.

In 1785, soon after retiring from the army, Scott married Ann Blackett, daughter of Sir Edward Blackett of Northumberland. His eldest son, William Henry Scott, followed him into the army. William Scott died in London in 1832. (GM 1785; PCC will proved 1832).

Our last captain is William John Darby, the son and grandson of army officers. The family identified themselves as English, though they also seem to have been closely connected to the Darby’s of Leap Castle, Kings County (now Offaly), Ireland. His grandfather, John Darby, was an army officer for 36 years, serving through most of the Duke of Marlborough’s campaigns. He was wounded at Malplaquet and ended his career as first major to the 3rd Foot Guards. His father, another John, was another career officer, and entered the 17th Foot as a captain in November of 1748. He became major to the regiment in 1756 and lieutenant colonel in 1759, retiring in 1775. John Darby thus commanded the regiment for much of the Seven Years War, Pontiac’s Rebellion, and for its peacetime postings until the eve of the American Revolution. (see Loudon Papers LO5241, 1757 Memorial of John Darby to Earl Loudon).

William John Darby was born in 1751, the eldest son of John and Sarah Darby. His entry into the service sheds light on the practice (rare in the army but common in the navy of the time) of commissioning children as officers. He was listed as a volunteer with the regiment in 1761 and purchased an ensign’s commission on May 6, 1762. The nature of his service became clear when he purchased his lieutenantcy in June of 1766. In October of that year General Gage forwarded a petition from five of the senior ensigns of the 17th complaining that Darby had been allowed to purchase over their heads. All veterans of the final campaigns of the Seven Years War, they “were agreeved in a very extraordinary manner” by his promotion. Young Darby “tho now upwards of four years in the Regiment has never joined it, perhaps by his very tender and early youth unable to undergo the hardships and fatigues of the Service...During this interval the Memorialists very chearfully performed Mr. Darby’s Regimental Duty, nor did they ever complain…knowing he was necessarily kept at his education & still more particularly; as he was son to a Field Officer of the Regiment…” While the system was often unfair and heavily weighted against those without influence, this time Secretary at War Barrington intervened to “protect…officers of merit and Service” and returned Darby to his former rank. He had to wait until November 24, 1769, to purchase his lieutenantcy. (WO1: 7 f. 182, Memorial of Ensigns Magill Wallace, Abernethy Cargill, Thomas Vanderdussen, Thomas Yeamans Elliot & James Howetson of 17th to General Gage; f. 188 Monckton to Barrington 11 Dec, 1766; and f. 190 Gage to Barrington 11 Dec. 1766.)

In spite of a somewhat rocky start, William John proved himself a valuable member of the regiment once he became an active officer. He purchased the adjutantcy in 1773, thus becoming responsible for the discipline of the regiment. He became captain in the regiment on Dec. 12, 1774, and commanded the light infantry company from April of 1775 until he was succeeded by William Scott in 1777. He returned to a line company and was captured with the regiment at Stony Point. Darby was exchanged late in 1780 and rejoined the regiment in time to provide extensive testimony at the court-martial of Lieutenant Colonel Johnston. He was promoted out of the regiment in the middle of the trial, on Feb. 8, 1781, when he purchased the majority of the 7th Foot. Most of the 7th had been captured several weeks earlier at Tarleton’s disastrous defeat at the Cowpens, and, as one of the few officers remaining, Darby was probably employed rebuilding the unit.

The 7th returned home in 1783. Darby married Ann White of London in 1788, became lieutenant colonel of the 44th Foot on June 13, 1789, and retired in 1794. He died at Bath in 1826. (GM, PCC proved 1826).

The careers of these three men demonstrate the striking continuity of service at the company level of many of the officers of the 17th. None of the three achieved higher rank than captain while with the regiment. Tew spent twenty-two years in the regiment before dying in service, Scott thirteen years before achieving a comfortable retirement by a quick promotion out of the regiment, and Darby (though perhaps the first four years shouldn’t count) served for twenty years before being promoted out of the 17th. The regiment benefitted greatly by the leadership and professionalism provided by long-service officers like these three, and Robert Clayton, the subject of our first blog.

MARK ODINTZ PHd.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history.

MARK ODINTZ PHd.Mark conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history.

Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.