A Few Notes on Military Works in North America, 1690-1779

All images are of books in the collection of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum. The numbers in parentheses are the volume’s catalog number in the museum’s library. Photo credit: Robert S. Bartgis.

As early as An Abridgement of the English Military Discipline (Boston, 1690), American colonists were printing their own military titles. A number of these titles were reprints of London properties, but the colonial editions were often "enlarged" or “improved” for the needs of the local market.”[1]

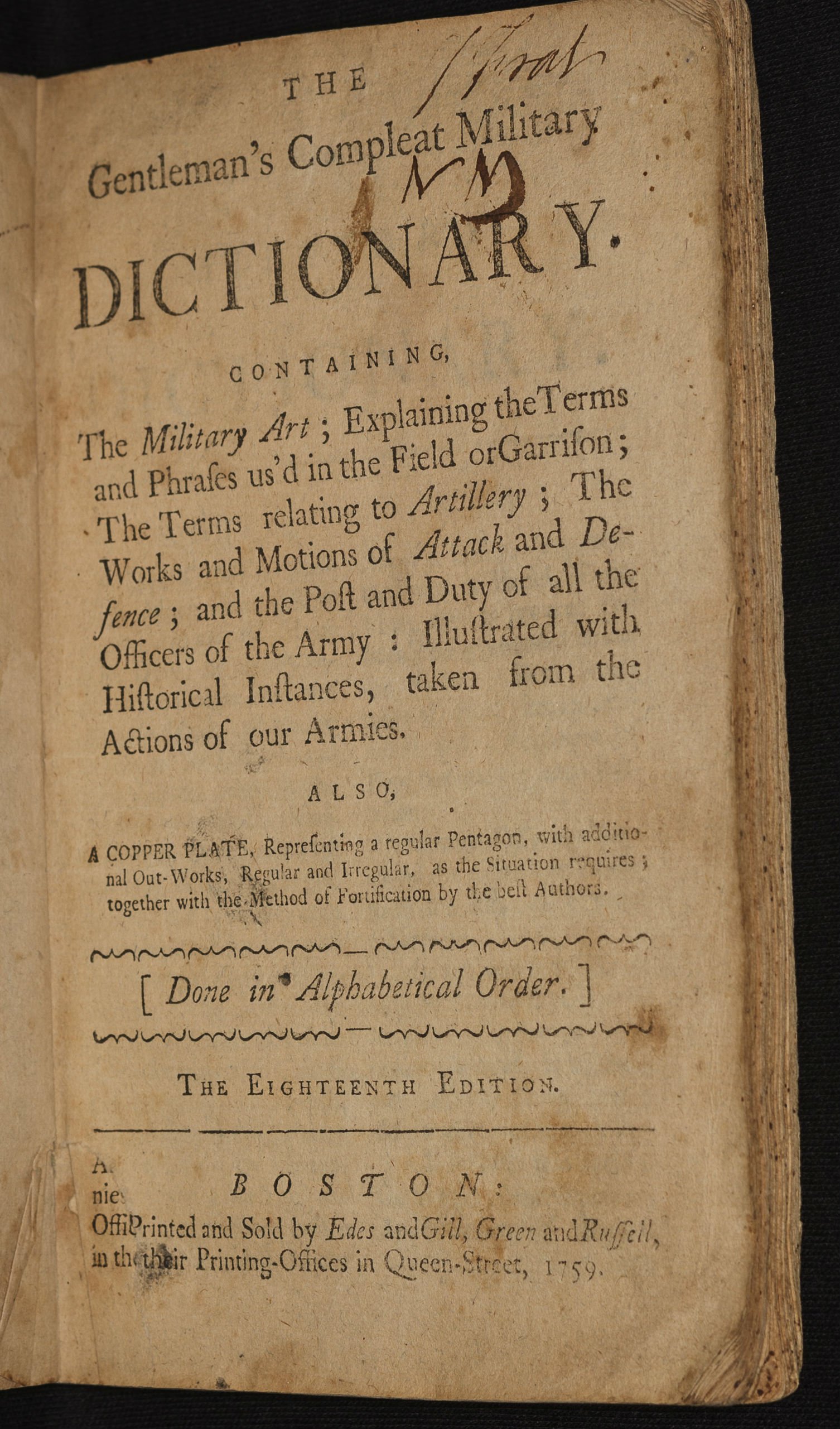

Early titles were short: printed in smaller formats and often sold as pamphlets instead of bound books. They included manuals for militia drill, military dictionaries, and abstracts of longer works.

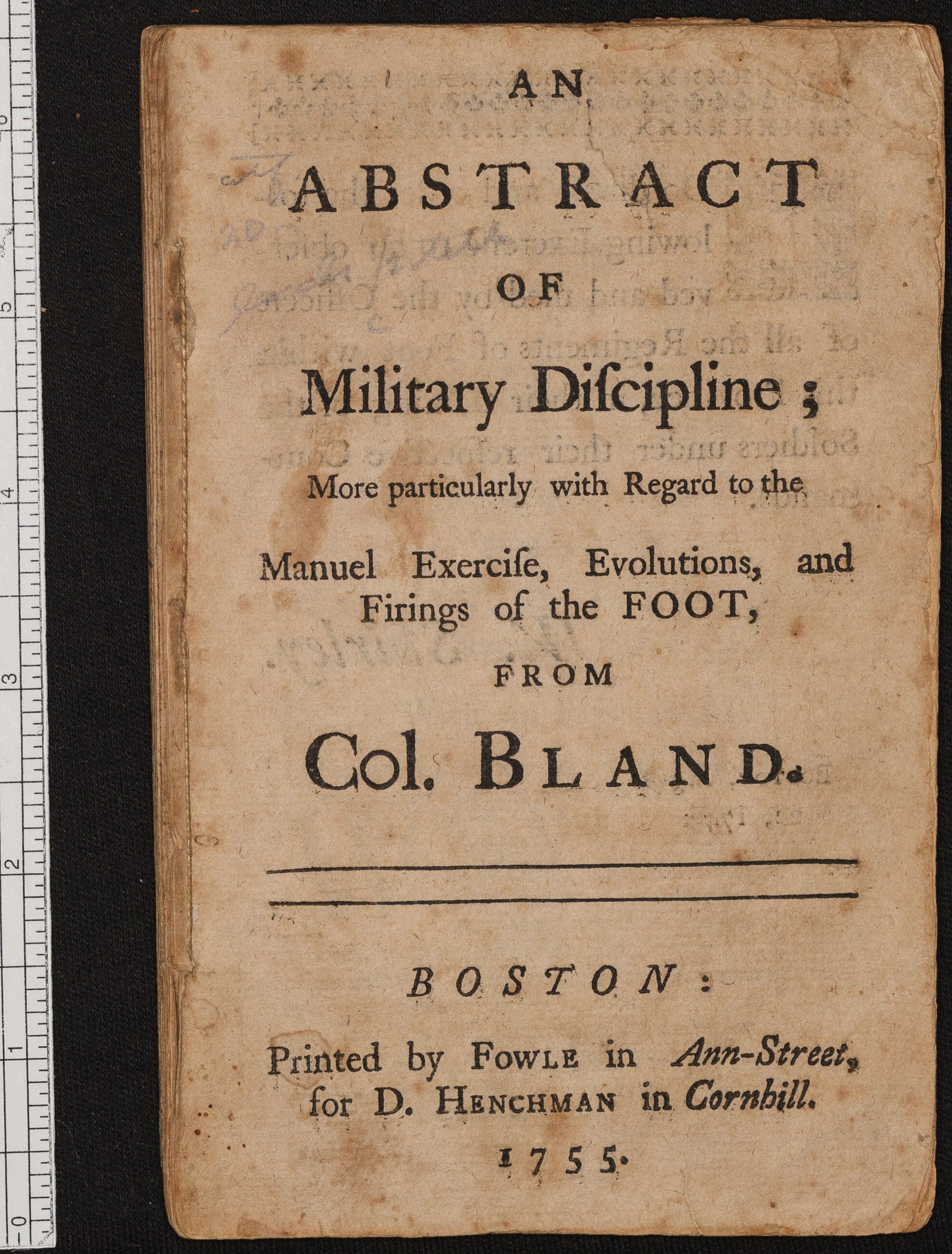

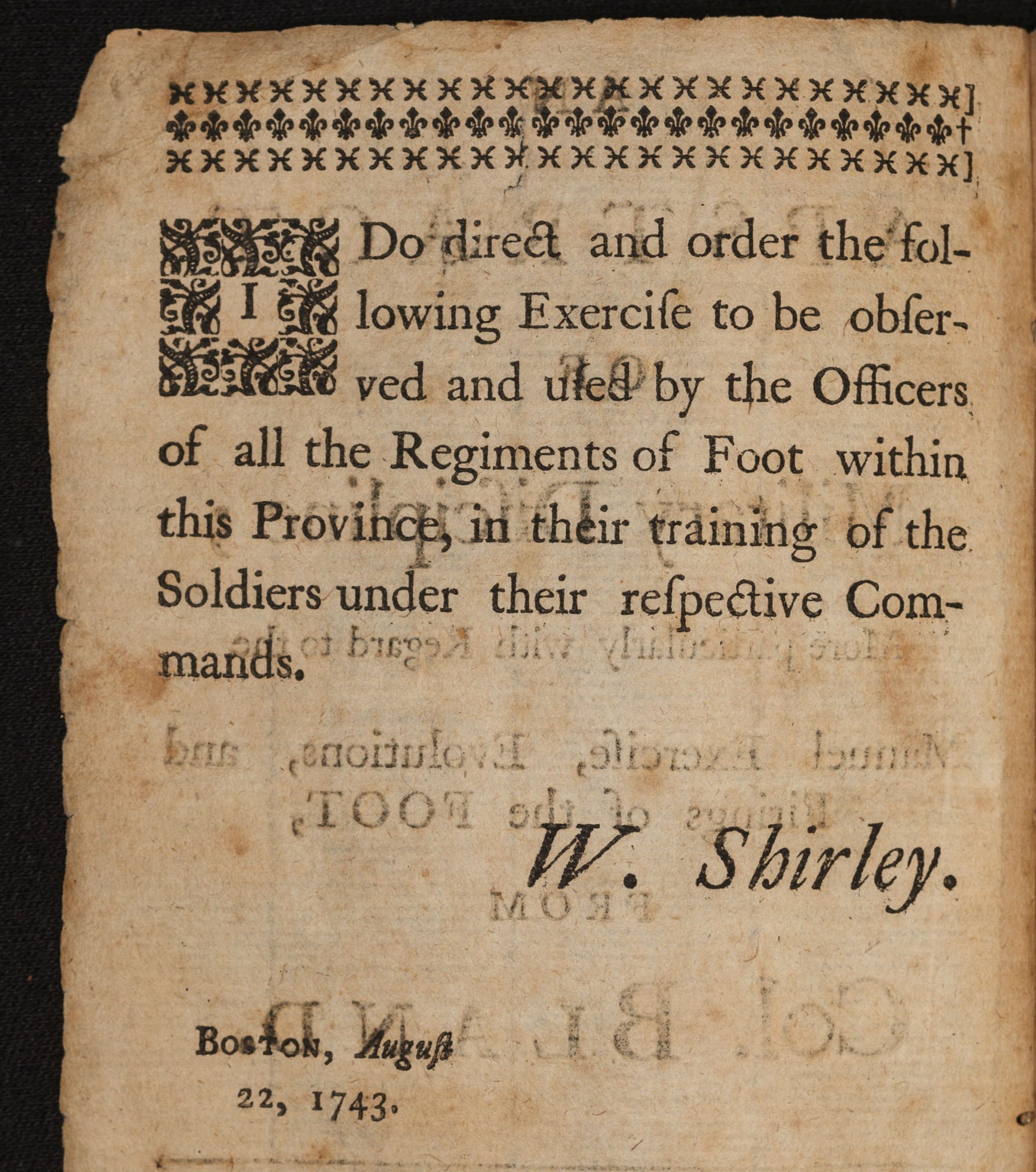

An Abstract of Military Discipline. Boston, 1755. (586)

An Abstract of Military Discipline. Boston, 1755. (586)

The Gentleman’s Compleat Military Dictionary. Boston, 1759 (831).

The Gentleman’s Compleat Military Dictionary. Boston, 1759 (831).

This reflected the general state of the printing market in America before the 1770s, where most printers focused on shorter works. The market books was uncertain, and many American printers lacked the capital or desire to risk publishing longer books that might languish unsold. Some exceptions were books printed by subscription, books with guaranteed buyers such as government publications of laws and edicts, and regular sellers like psalters, books of sermons, and school books.[2]

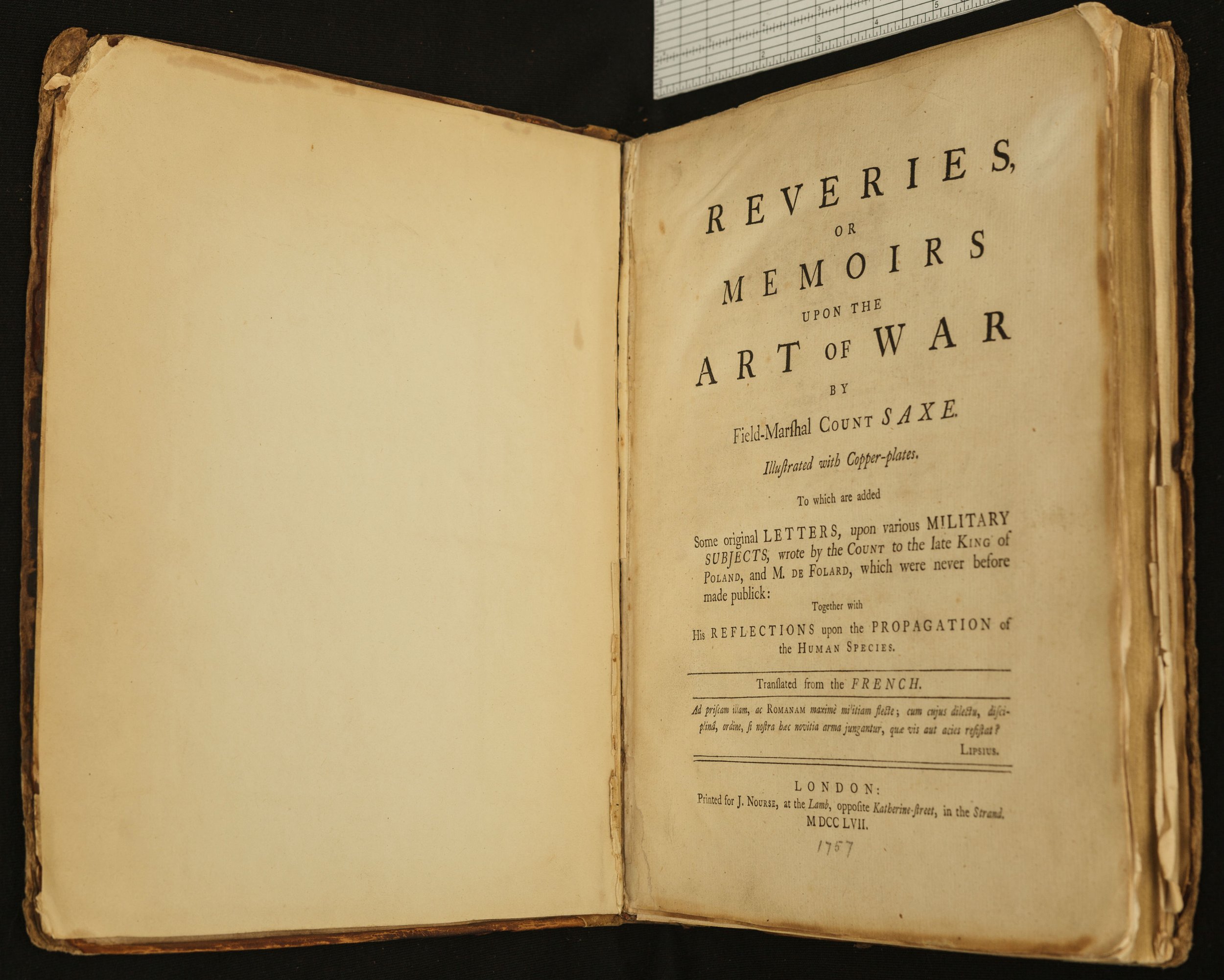

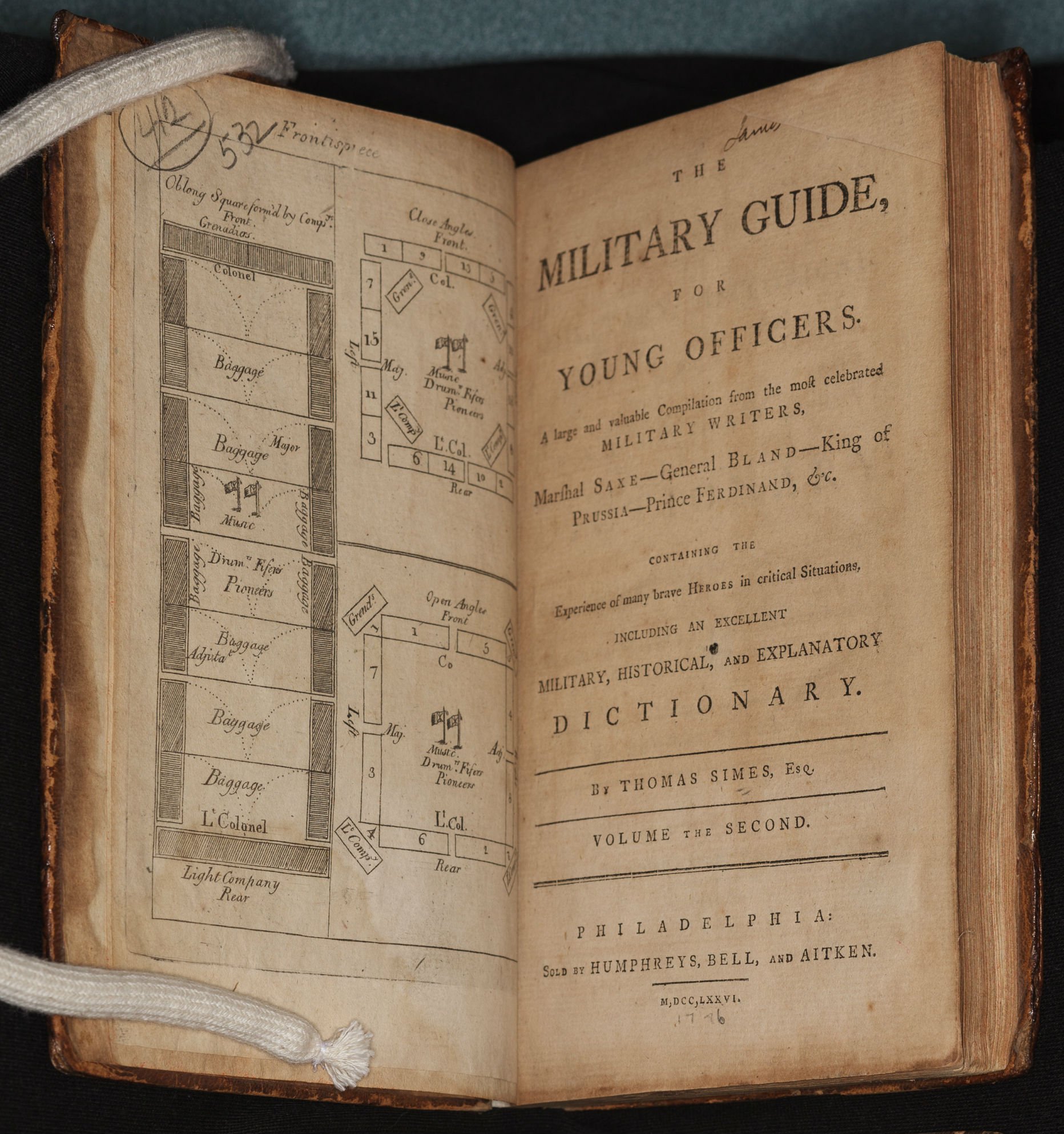

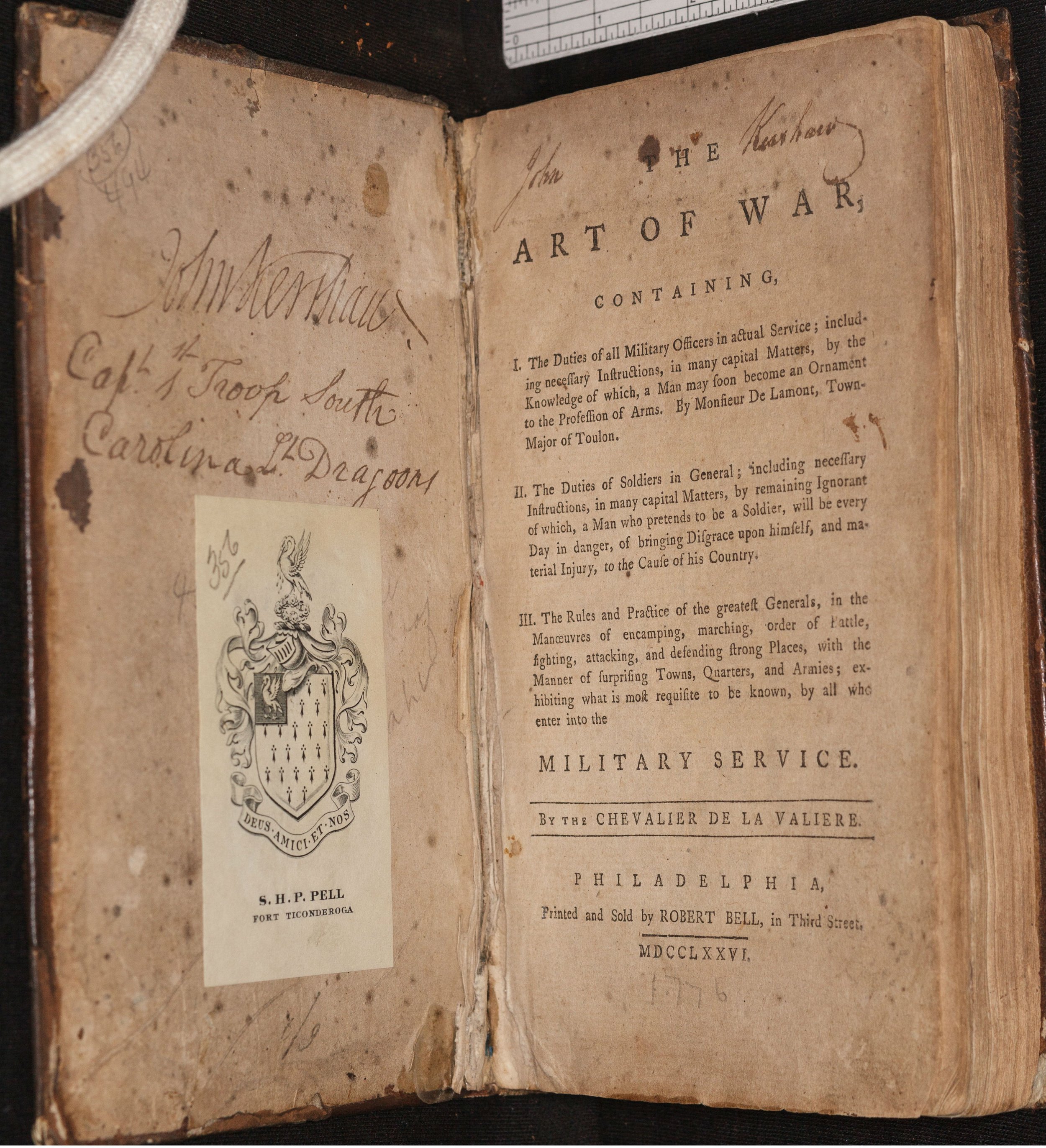

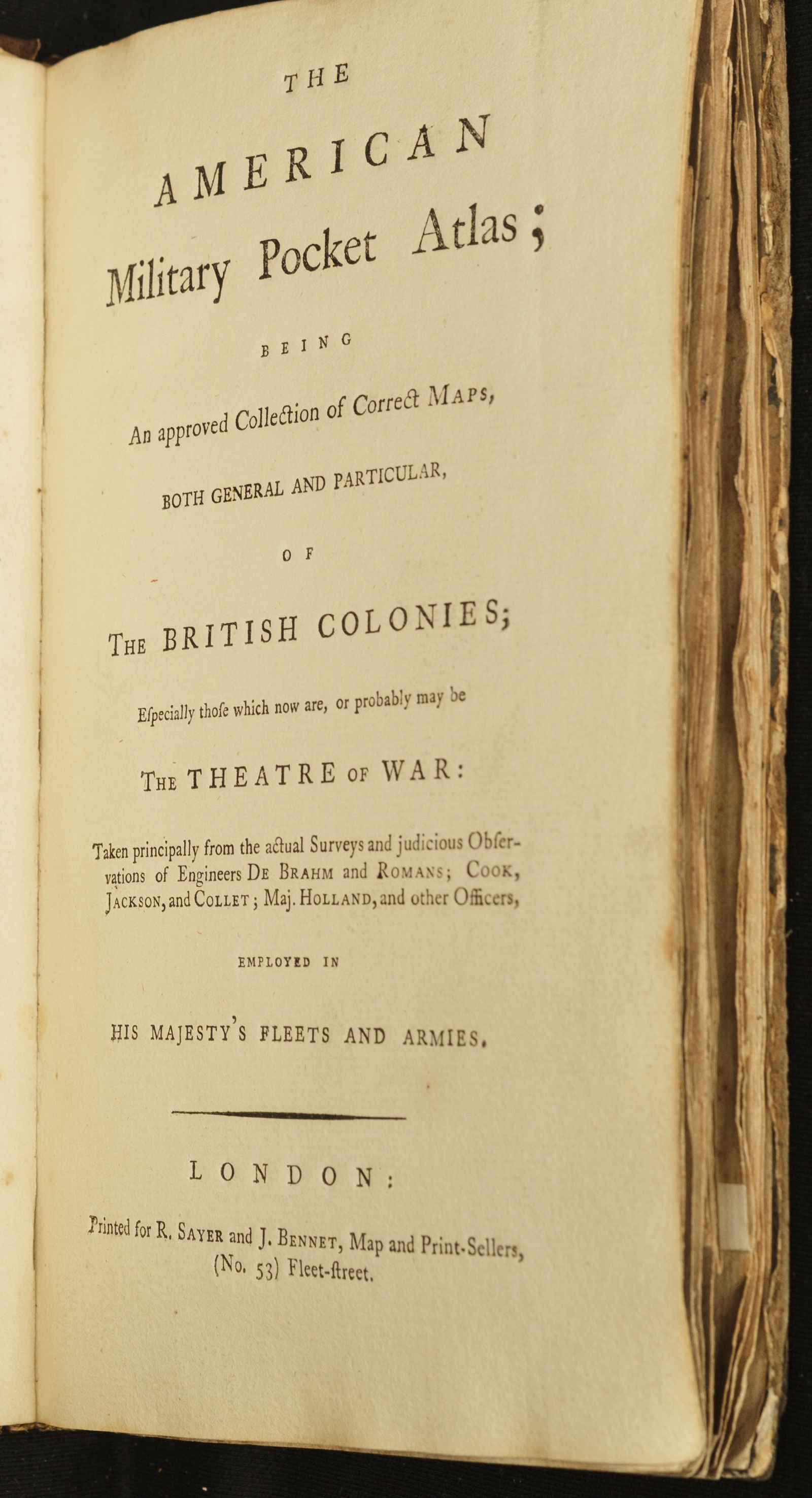

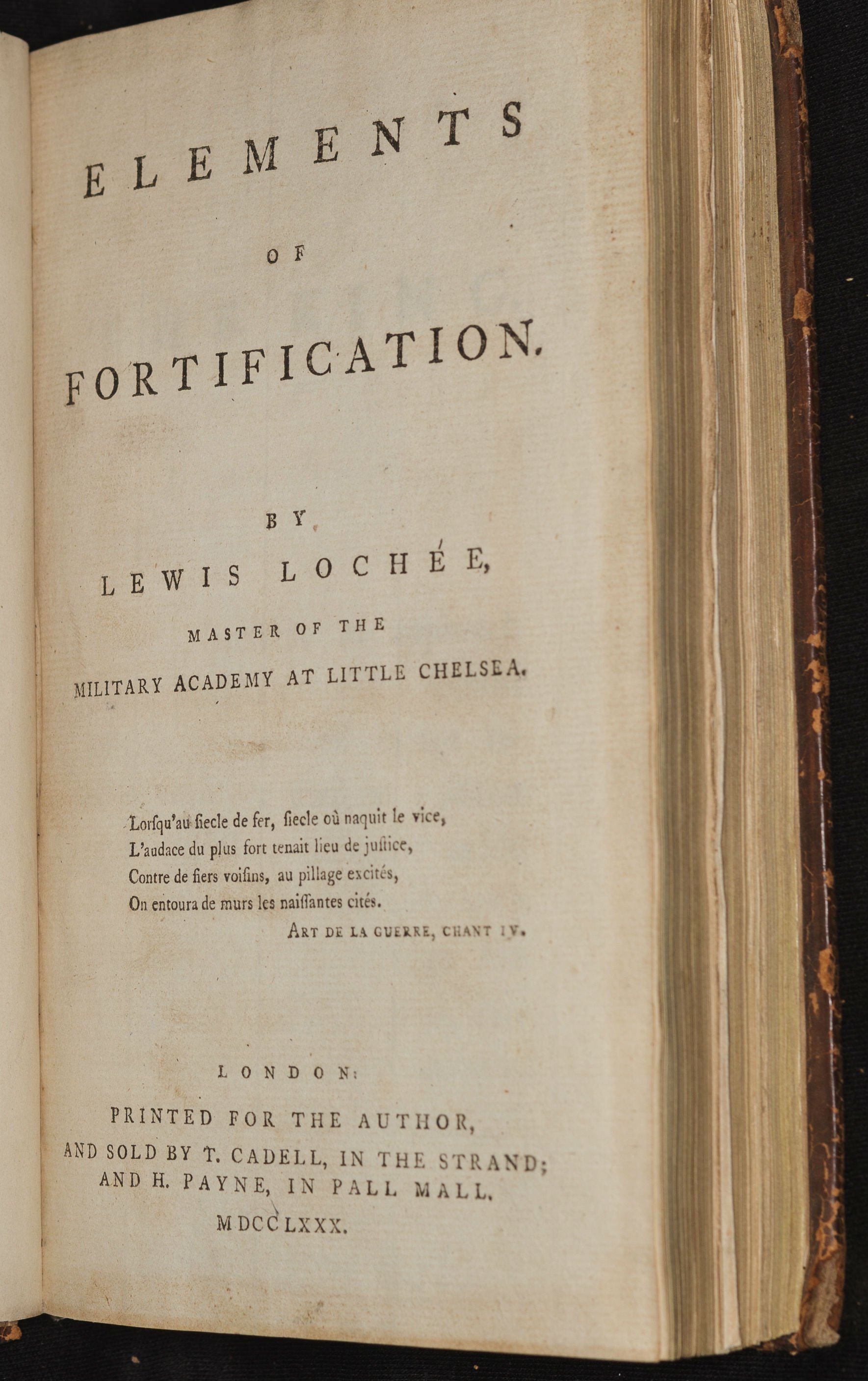

As a result, in 18th century America most longer specialty works were imported, either at the request of a buyer or by a bookseller who bought from a publisher in England and advertised the titles available.[3] Thus when the officers of the continental army and militias such as George Washington and Henry Knox educated themselves in military theory, they were usually reading London imprints of standard works by Bland, Simes, Saxe, and so on.

“As to the manual exercise, the evolutions and manoeuvres of a regiment, with other knowledge necessary to the solider, you will acquire them from those authors who have treated upon these subjects, among whom Bland (the newest edition) stands foremost; also an Essay on the Art of War; Instructions for Officers, lately published in Philadelphia; the Partisan; Young; and others.”

- George Washington to William Woodford, November 10, 1775

The status quo began to change in 1775, as the heightening of hostilities between the colonies and Great Britain created a flood of demand for military books that could not keep up with imports.

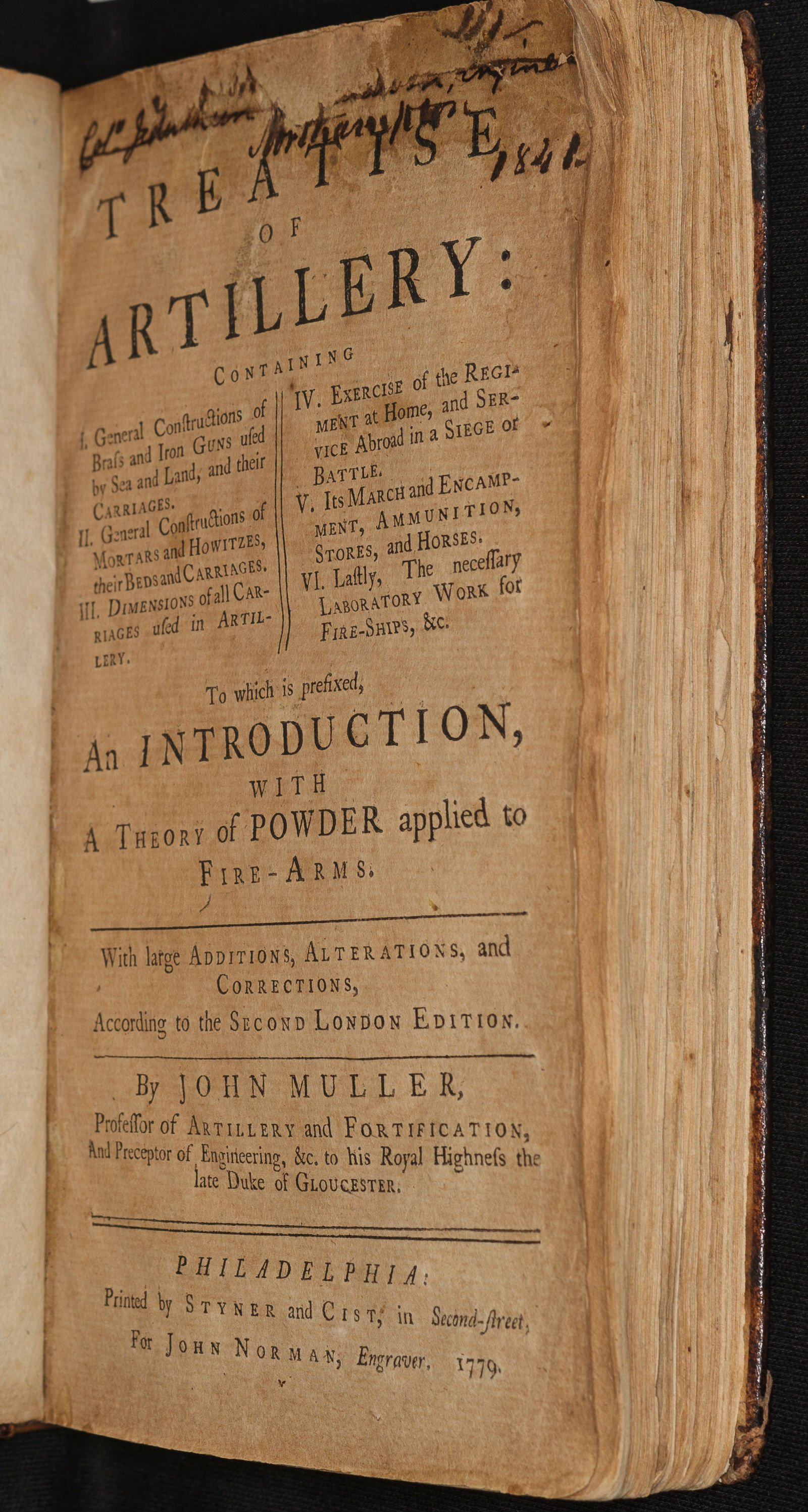

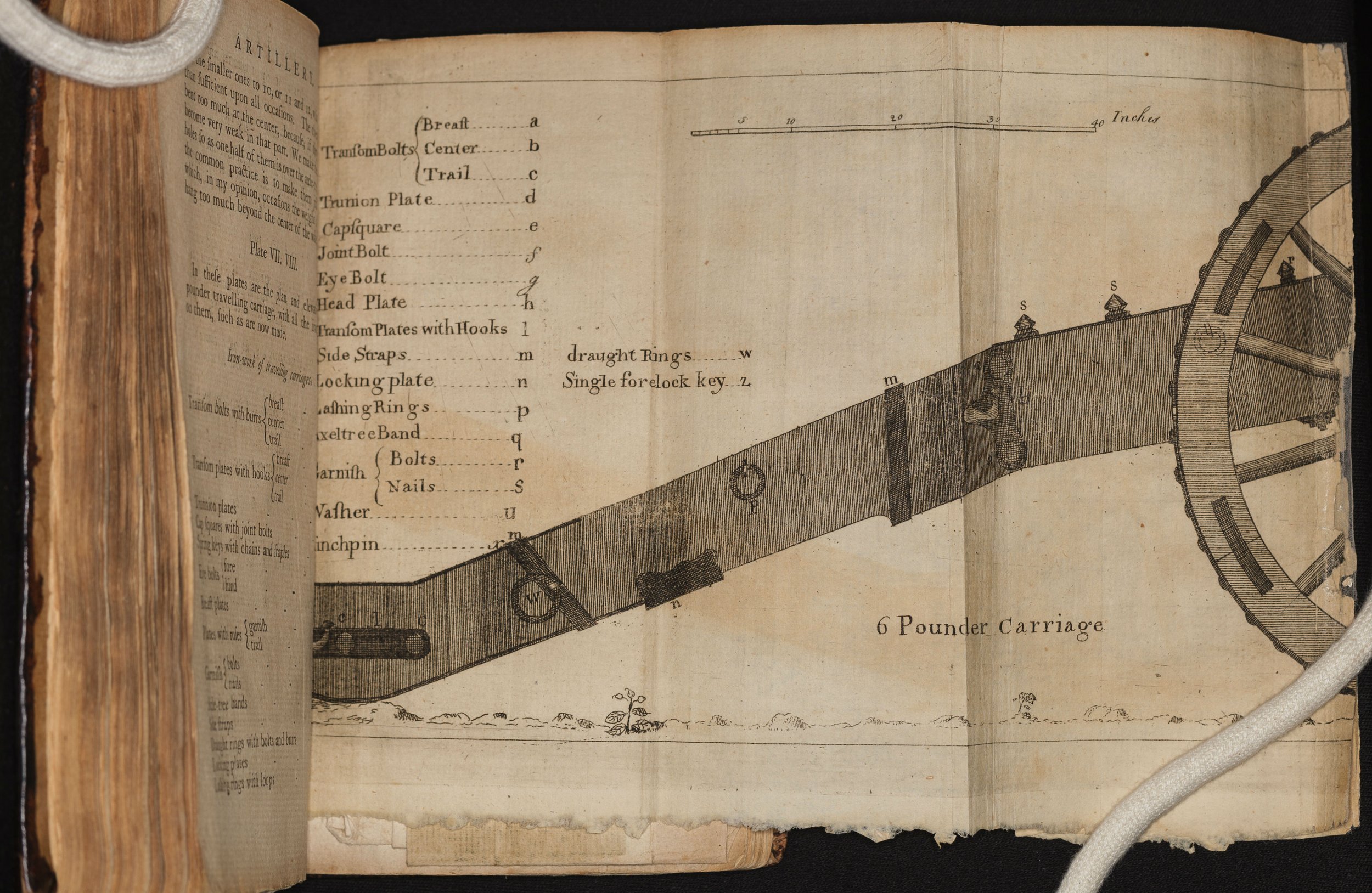

“Much of this activity was centered in Philadelphia, where more than thirty works on military subjects were published in the years 1775 and 1776 alone. Initially these books were reprints or new editions of British or European standards, but publishers quickly turned to a new generation of American military authors whose works reflected the immediacy of the war.”[4]

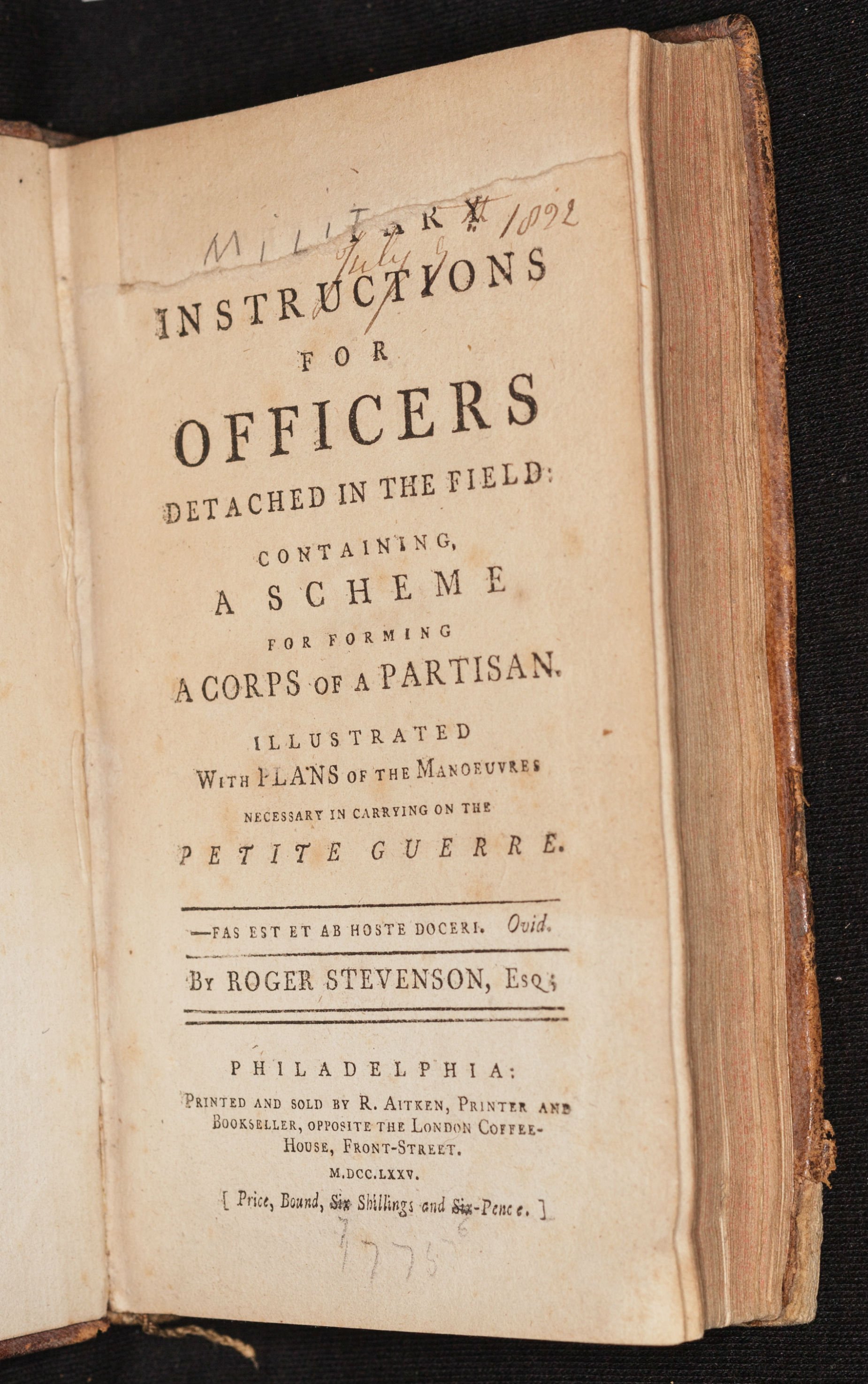

“In a country where every gentleman is a soldier, and every soldier a student in the art of war, it necessarily follows that military treatises will be considerably sought after, and attended to”, wrote Hugh Henry Ferguson in 1775, after editing the American edition of “Military Instructions for Officers Detached in the Field”, a Philadelphia publication. This book was a best-seller for the printer Robert Aitken, who collaborated with two other Philadelphia printers, James Humphreys, Jr. and Robert Bell, to spread out the cost, particularly of paper (roughly 75% of the cost), as well as the book’s copperplate illustrations.

On May 16, 1776 Henry Knox wrote to John Adams about the need for more books:

On May 16, 1776 Henry Knox wrote to John Adams about the need for more books:

“The officers of the army are very difficient [sic] in Books upon the military art which does not arise from their disinclination to read but the impossibility of procuring the Books in America; something has been done to remedy this at Philadelphia and I hope they will not stop short.”

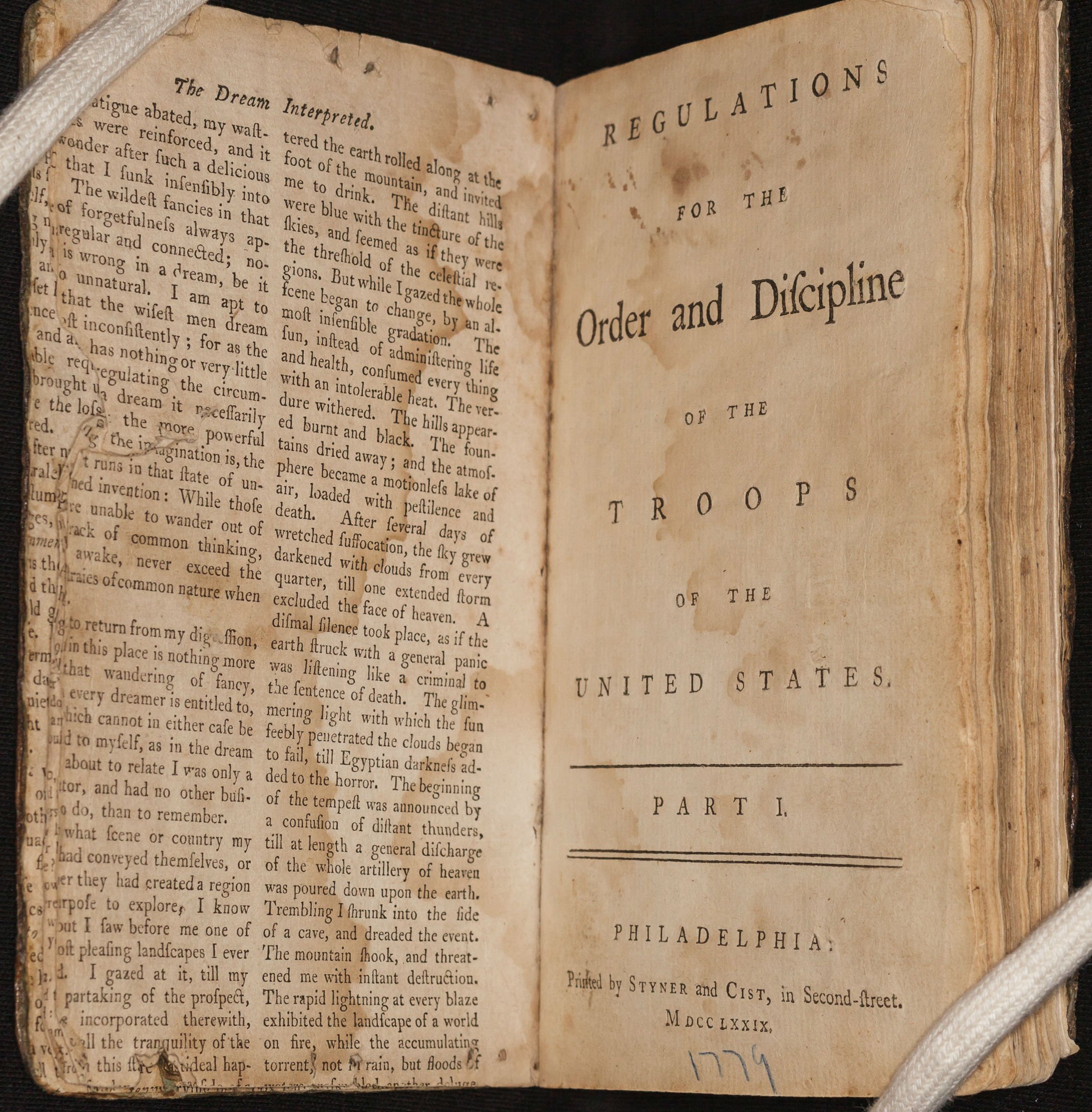

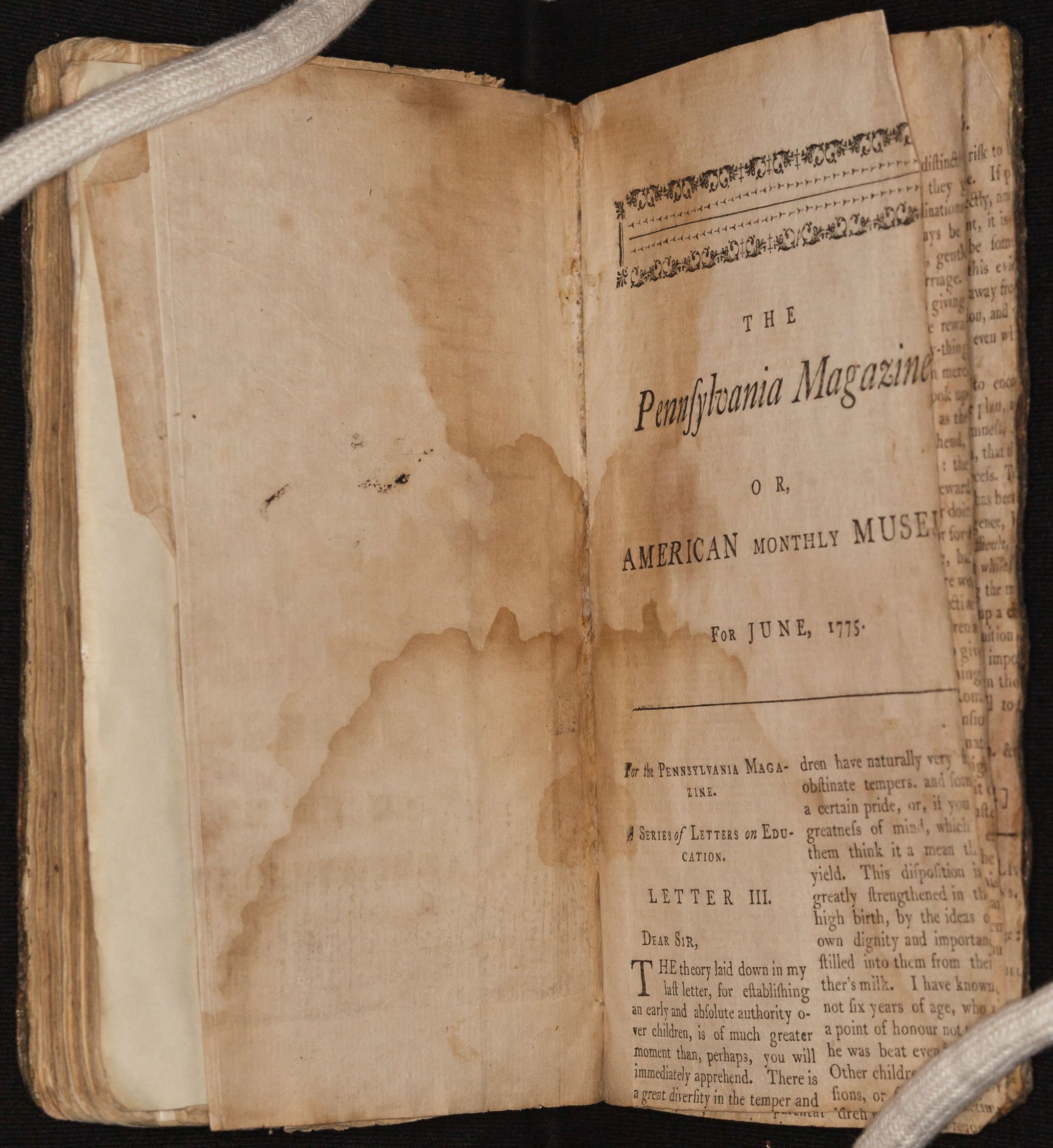

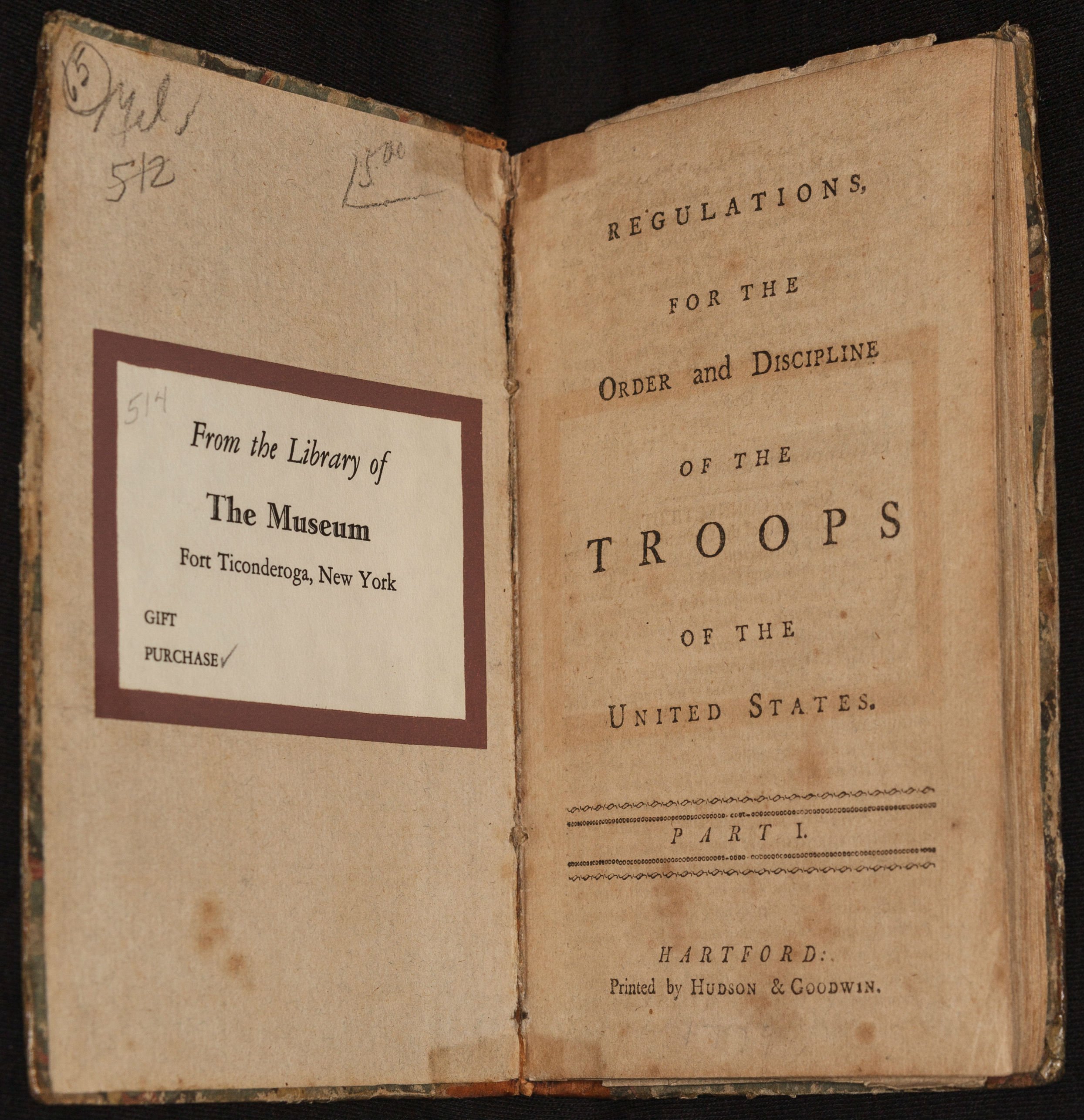

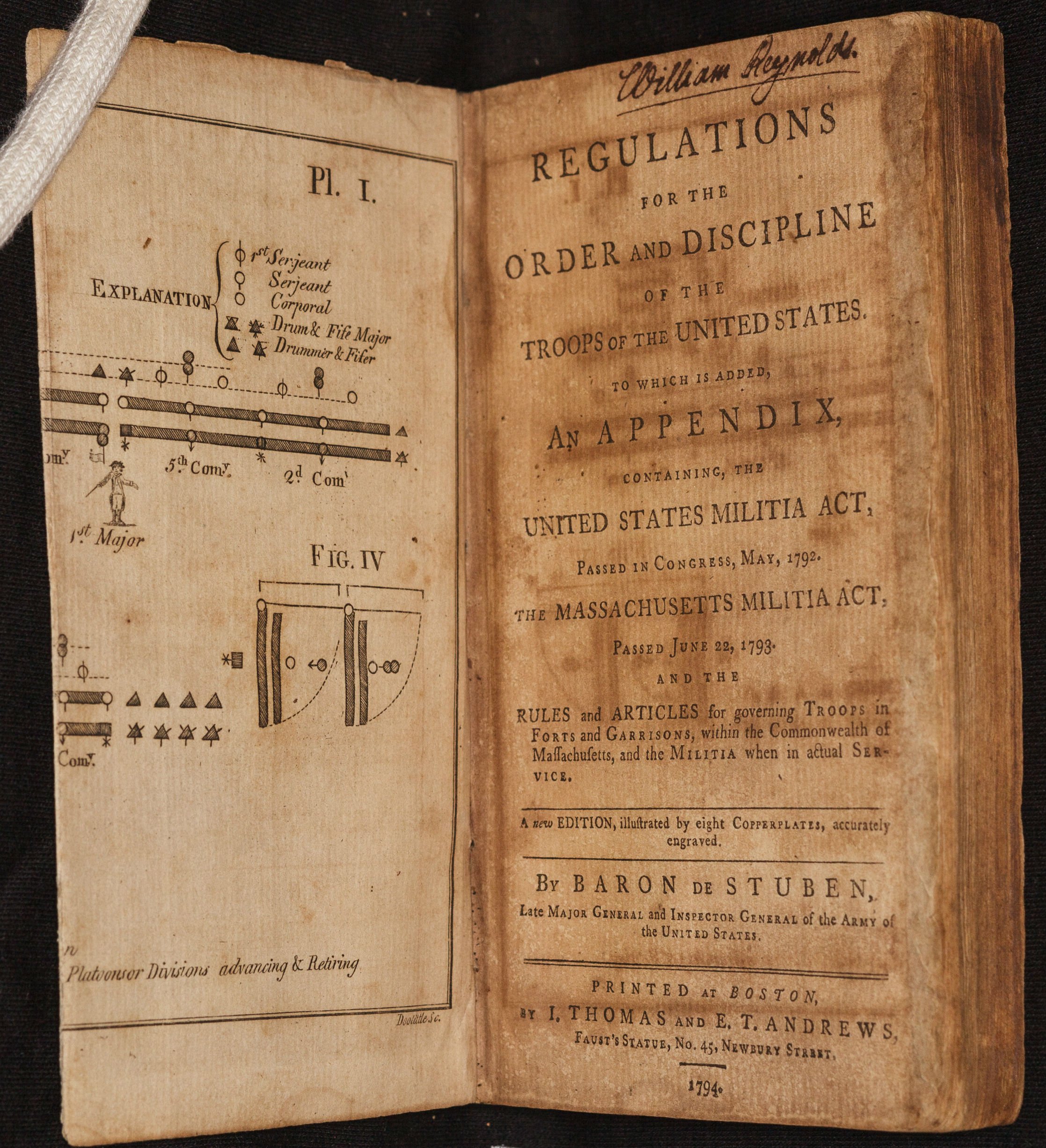

The British occupation of Philadelphia between September 1777 and June 1778 disrupted the city’s production of military works, but by 1779 another volume had appeared on the market: General Von Steuben’s “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States”. Paper was so short for the first edition that the printer used waste from the Pennsylvania Magazine for endpapers and spine linings. [5]

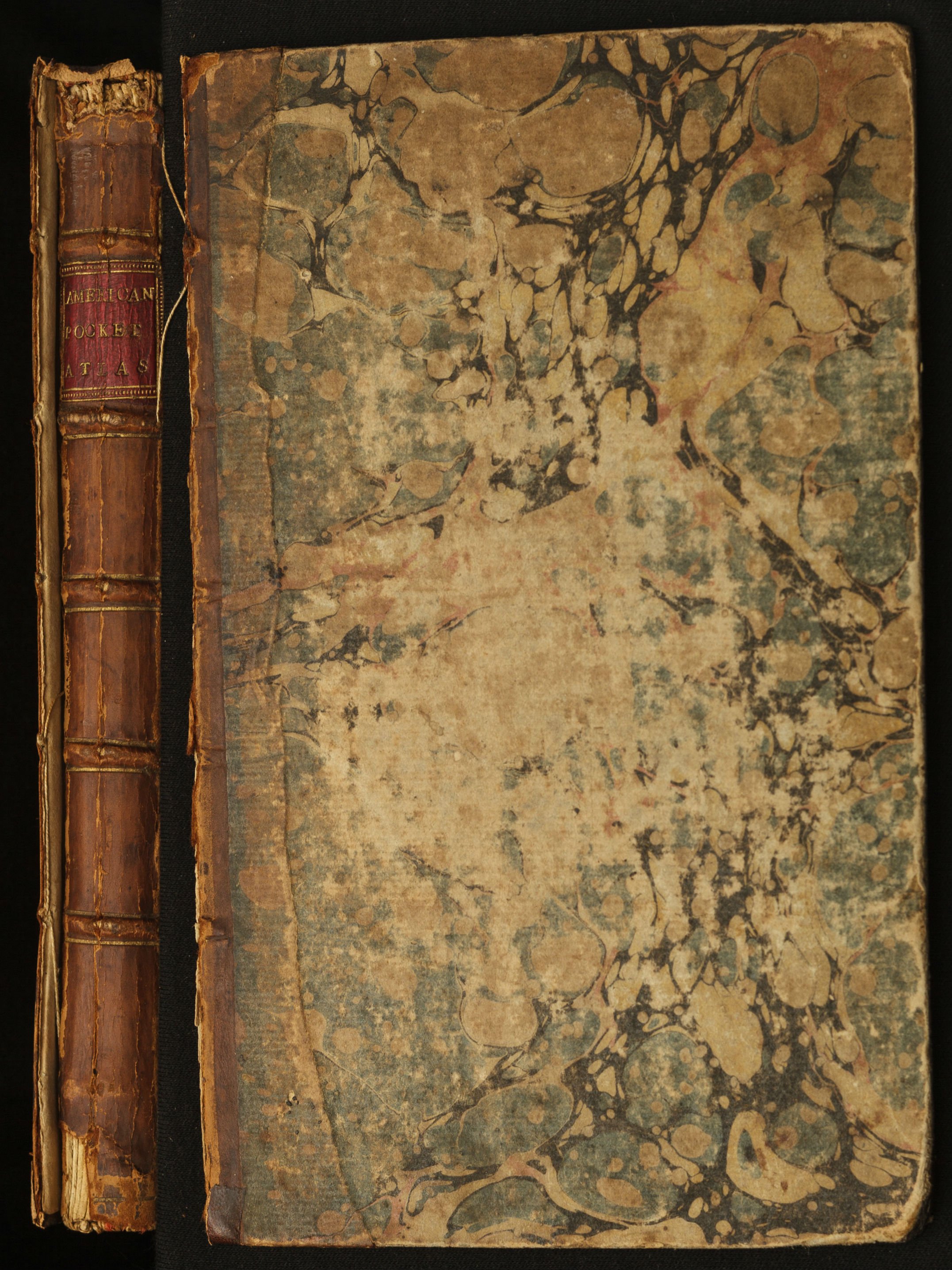

Surviving copies attest to the poor quality of the paper available to the printers in 1779: brown from being made from lower quality rags and brittle from ineffective attempts to whiten the paper pulp paper with lime, with a heavy impression of the laid wire screen used to form each sheet. These wartime books stand in stark contrast to the supple white text block papers and marbled paper covers of some of the elegant treatises published contemporaneously in London.

Von Steuben’s manual was reproduced throughout the course of the war, not just in Philadelphia but in other cities such as Boston, Massachusetts and Hartford, Connecticut.

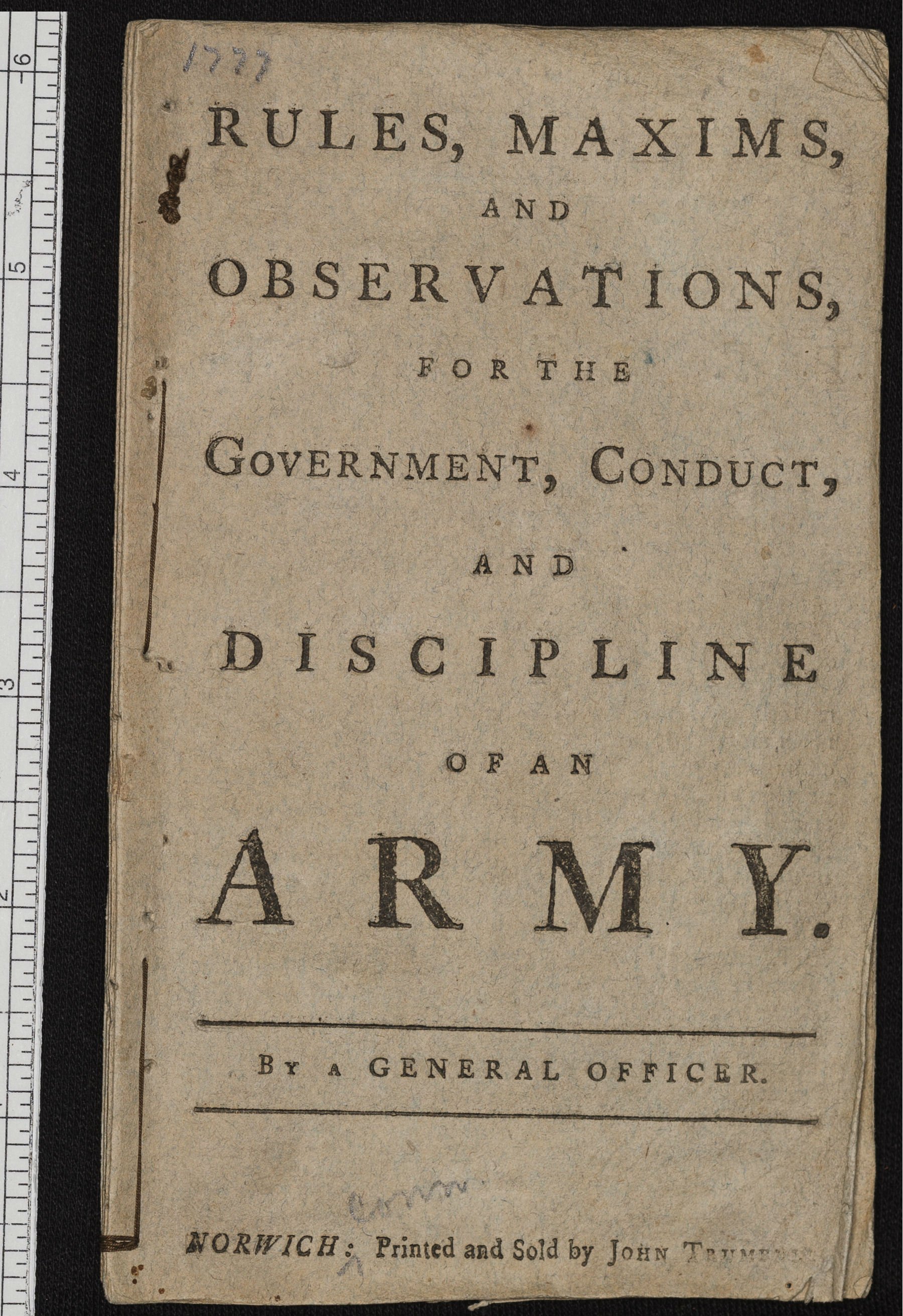

Other wartime American publications included A Treatise of Artillery, and the Rules for an Army, the latter printed in Norwich, CT. Norwich had a population of about two thousand people at the time, and the printing of a manual in even so small a town demonstrates the huge demand for military literature during the war. [6]

Between imports and domestic publication at least some American officers were able to fulfill their desire for military works, since Hessian commander Johann von Ewald wrote that,

“I was sometimes astonished when American baggage fell into our hands during that war to see how every wretched knapsack in which were only a few shirts and a pair of torn breeches would be filled up with military books.”

After the end of the war Von Steuben’s Regulations would be reprinted regularly throughout the new American states, along with many other new titles for the fledgling country.

Footnotes: [1] A History of the Book in America, Volume 1: The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World, p. 85[2] Ibid, p. 156.[3] Ibid, p. 185.[4] Books in the Field: Studying the Art of War in Revolutionary America. Exhibit catalog, Society of the Cincinnati, 2017. P. 10.[5] Ibid, p. 12.[6] Phone interview with M. Keagle, 16 October 2017

BEN BARTGISBen Bartgis is a book conservator technician at a very large institution. This talk is excerpted from a presentation he gave at Ft. Ticonderoga in November 2017: "Bound for War: The Military Manual as Object in the Handpress Era".