Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

SUTTLING in the WAR for INDEPENDENCE

Suttlingin the period of the American Revolution does not change much from the previousconflict although information is a bit more abundant. There is an increase of rules and regulationsgoverning the practice(s) of the Sutler. Several studies of the subject have been done including works by John U.Reese, W. Tatum Ph.D. and the 18th Century Material Culture ResourceCenter. The one text devoted to thesubject of followers is Holly A. Mayer Ph.D.’s book Belonging to the Army(University of South Carolina Press, Columbia South Carolina). Dr. Mayer’s work is focused on theContinental side of the conflict but parallels surly can be drawn.

Thefirst regulation and perhaps most mentioned on either side of the conflict isthat only “One Sutler” per regiment or brigade will be allowed and that Sutleronly licensed upon the recommendation of the commander. I surmise that this was in response to eithermore Sutler’s attempting to attach themselves to the army (looking to turn aprofit) or as we will see a common occurrence is the over sale of Liquor to thetroops. In addition to the single sutlerrule, there is a strong statement that the Colonel of the regiment beanswerable for the conduct of the sutler appointed.

General Orders, W.O. Boston 22June, 1775 (5 Days After the Battle of Breed’s Hill)

“All persons belonging to, or followers of the Army, are forbid to sell spiritous liquors, excepting at the regimental Canteens, one and only one of them is allowed for each Regiment subject to the regulation of the Officer Commanding it; and as the appointment of the Sutler depends on the commanding Officer of the Corps, it is expected henceforward they will be answerable for the sobriety of the Soldiers under their Command, all other sources for Spiritous liquors but that of the Canteen, being effectually stopped up from the A G Officers and Soldiers by the Proclamation”

Thenext regulation that appears is in regard to provision, sale, quality,quantity, price, and time of sale of Liquor and other spirits.

General Orders, W.O. Boston14October, 1775

“The Commanding Officers of Corps not to allow their Sutlers to sell liquors to Soldiers, or any other persons who do not belong to their respective Corps; Upon a conviction of a disobedience of this order, the liquors will be destroyed, and the delinquent not have leave to sell any in the future. Women belonging to the Army convicted of selling Spiritous liquors, will be confined in the Provosts till there is an opportunity of sending them from hence."

Orderly Book H.M. 47th Regimentof Foot Camp at River Bouquet 16 June, 1777

“The Sutlers are not on any pretence to sell Rum or any other Spirits to the Men without a Written Order from a Commission’d Officer and never in less Quantity than a Quart”

Furtherclarifications were made including regulations against “pretend sutlers” whowere selling alcohol, and a clarification that Sutlers were to sell alcohol toONLY the soldiers belonging to the regiment the sutler was licensed to. Having drunk soldiers and thus placing directblame on the Sutlers is common, if not to say, correct. An infraction of the set regulations mostoften ended with consequences that were somewhat standard. The guilty Sutler would have their stockconfiscated and ordered to leave the camp. Also license revocation was possible and the most severe punishmentwould have been from 50 to 100 lashes “upon the bare back” to be “well laidon”. We also see a trend in therepeated requests for the sutler names to be taken down and sent toheadquarters. My impression is so thatthe provost guard or Serjeant Major of the army may try to better regulate theactivity of Sutlers. Many times guilty offenderswould simply move shop and open a Tipling House or Dram Shop nearto, or even within the camp confines.

*ATipling House was a term used to describe a house, stall or booth in whichliquors are sold in drams or small quantities, to be drunk on thepremises. Often associated with illegalselling and consuming of liquor.

*A DramShop, or dramshop in this period is a bar, tavern or similar commercialestablishment where alcoholic beverages are sold. Traditionally, it is a shopwhere spirits were sold by the dram, a small unit of liquid.

These termsare common when regulations were being written or orders issued. Given theexamples below.

General, Sir William Howes Orders 23January, 1776

“The Commanding Officers of Corps to Suppress all Dram Shops in their Respective Districts that are not licensed by Brig.-Gen. Robertson.”

General Orders War Office RhodeIsland11 December, 1777

“Whereas the great Drunkenness that prevails among the Soldiers, proceeds from the Soldiers wives being allowed to keep little shops out of the districts of their Regiments, the Commanding Officers will give directions that they are not permitted to live out of the quarters of the Regiment they belong to.”

Standing Orders H.M. 71st Regiment of Foot15 August, 1778

“Whereas the great Drunkennes that prevails among the Soldiers, proceeds from the Soldiers wives being allowed to keep little shops out of the districts of their Regiments, the Commanding Officers will give directions that they are not permitted to live out of the quarters of the Regiment they belong to.”

Both the Continental and British Army developed “Articles of War” with the Americans “borrowing” much from their British cousins. In the British Articles of War, regulations were set down for the governance of Sutlers and we can see some similarities and differences between the two forces. In Section XIV, Article 23 of the British Articles: it states that sutlers, retainers, and others serving with the army were subject to orders “according to the Rules and Discipline of War”. A definition that allows for a large amount of “wiggle room” for those commanding. The American Articles on the other hand were more exact in the governance of the sutlers. Article 32 of the American Articles states: they are “subject to the articles, rules, and regulations of the Continental Army”. A more precise painting of the subject vs the broad strokes employed by the British, however as the war progressed the Americans re-evaluated these strict definitions, so in 1776 the Second Continental Articles of War established that Sutlers would be governed “according to the rules and discipline of war”, an echo of the British articles.

TheContinental Congress also closed a gap form the 1775 regulations in 1776. Unlike the British model that permitted allofficers, soldiers, and sutlers to bring into garrison “any Quantity or Speciesof Provisions, eatable or drinkable, except where any Contract or Contracts areor shall be entered into by Us, or by Our Order, for furnishing suchProvisions”, the American rules had no such provision, in 1776 the change is made, allowing “eatable ordrinkable” provisions not already contracted for be brought into camp. This article was further amended in 1777 toonly include “eatable” provisions. A bittoo much alcohol being offered perhaps. Additional rules included ones thatprohibit the sutler from staying open past 9 O’clock and not opening “before thebeating of the reveilles, or upon Sundays, during divine service orsermon”. Price gouging was alsoaddressed and in the American Continental orders, the officers were to see toit that soldiers were supplied “with good and wholesome provisions at themarket-price”, and in Article 4, the sutlers received like protection. Officers were to be sure that “exorbitantprices for houses or stalls, let out to sutlers” not be charged.

From“Belonging to the Army” Dr. Mayer’s states:

"Sutlers were merchants or traders permitted to sell provisions to the troops. Business-minded individuals, whether self-employed peddlers or representatives of some of America's bigger mercantile concerns, saw opportunity beckon as early as the spring of 1775 when New England militia units camped around Boston. They carted their goods in and set up shop. Some then attempted to stay with the forces that were united into the Continental Army”

I believethere are few differences between Sutlers following the Continental vs theBritish Army in America owing to the fact the role of the Sutler having beenmore evolved within the British establishment simply due to the fact they hadbeen doing this “Sutler Thing” longer.

We occasionally get a glimpse into what day to day life was like. In The History of Henry Esmond by William Makepeace Thackeray, originally published in 1852. A story of the early life of Henry Esmond, a colonel in the service of Queen Anne set against the backdrop of late 17th- and early 18th-century England. Although fiction, the tale related here may help to demonstrate the role the sutler played in the life of the soldier in the 18th century.

Turning from fiction, there is nothing much more exciting than finding a “firsthand” account regarding either a sutler or sutler activity. In the memoir “Westward into Kentucky, the Narrative of Daniel Trabue”, Edited by Chester Raymond Young, The University Press of Kentucky. Trabue in 1827 wrote down his many stories from his life, now the 148 pages are preserved in the Lyman Copeland Draper manuscripts in the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Included in these pages are the narrative of his time spent in and around the Continental Army specifically during the Yorktown campaign in 1781, where he joins the Militia and soon volunteers to carry dispatches to “General Layfatte”. In one of his recollections he tells the tale of an interaction with a tavern keeper while carrying dispatches. After getting a drink he sees a mounted British patrol coming his way, Trabue makes his escape and the tavernkeeper shouts “Don’t get ketched!” When he reaches the General and delivers his dispatches and after being asked many questions, he “applied to him for a permit to be a sutle to his army.” Which “He [Lafayette] imedeately had one wrote”. Trabue, permit in hand, now must find something to sell. He went into the camps and observed the different men “selling spirits.” and finds a “Dutchman” who had just arrived with “a fine teame and a good load of Brandy and Whiskey and two very large sacks of sweet bred.” Trabue seeing an opportunity asks the Dutchman “Have you a permit to sell your spirits?” which he answers in the negative. He lets the Dutchman know that he heard that any illegal sales would result in confiscation of all possessions including wagons and spirits. He [Trabue] tells him he has a permit and offers to go “halfs” with him? The Dutchman is unimpressed and ignores the offer, that is, until in Trabue’s words, “here comes the Ajatent and says, ‘whoes wagon and spirits is this?’” Needless to say, the Dutchman takes up the offer, and the guard is turned away. Trabue later goes on to describe how all the other wagons and spirits were impressed and the two “made a very handsom profit.” However, this good fortune was short lived. Once out of camp Trabue’s new business partner decided he would not go into the camp again for fear of losing his wagon, “he would take his wagon home and pull of[f] the wheels”. This left Trabue looking for a new opportunity. Finally, he asks General “Fayette” for leave to go home and find a team, wagon and anything else he can sell. He finds Brandy and Rum however that’s the last mention of his adventures as a Sutler in his narrative.

Includedhere are the American Articles of War that pertain to Sutlers in 1776. These having been referenced prior. Inreading them an even better understanding of the role of the sutler may begained.

AMERICAN ARTICLES of WAR September 20th 1776

SECTIONVIII

Art. 1.No suttler shall be permitted to sell any kind of liquors or victuals, or tokeep their houses or shops open, for the entertainment of soldiers, after nineat night, or before the beating of the reveilles, or upon Sundays, duringdivine service, or sermon, on the penalty of being dismissed from all futuresettling.

Art. 2.All officers, soldiers and suttlers, shall have full liberty to bring into anyof the forts or garrisons of the United American States, any quantity orspecies of provisions, eatable or drinkable, except where any contract orcontracts are, or shall be entered into by Congress, or by their order, forfurnishing such provisions, and with respect only to the species of provisionsso contracted for.

Art. 3.All officers, commanding in the forts, barracks, or garrisons of the UnitedStates, are hereby required to see, that the persons permitted to settle, shallsupply the soldiers with good and wholesome provisions at the market price, asthey shall be answerable for their neglect.

Art. 4.No officers, commanding in any of the garrisons, forts, or barracks of theUnited States, shall either themselves exact exorbitant prices for houses orstalls let out to settlers, or shall connive at the like exactions in others;nor, by their own authority and for their private advantage, shall they lay anyduty or imposition upon, or be interested in the sale of such victuals liquors,or other necessaries of life, which are brought into the garrison, fort, orbarracks, for the use of the soldiers, on the penalty of being discharged fromthe service.

While at Valley Forge orders were given that a board of General Officers meet and decide upon the rules for Suttling. The results of this meeting were as follows and gives us an idea as to what alcohol was available during the winter of 1777-78. This also tells us that tobacco in several forms was available.

HeadQuarters V: F: January 26th 1778.

MajorGinl. Tomarrno Grebn

BrigadierMcIntosh

FieldOffV . . . LT Col Gray. Majr Braddish

B: M: MClurb

A BOARDof Genl Officers having recommended that a Sutler be appointed to each Brigadewhose Liquors shall be inspected by two Officers Appointed by the Brigadier forthat purpose and those Liquors sold under those restrictions as shall bethought reasonable the Commander in Chief is pleased to approve the aboveRecommendation and to order that such Brigade Sutlers be app^ and Liquors soldat the following prices and under the following Regulations each

Brandyby the Quart 7/6 by the pint 4/ By the Jill 1/3

Whiskyand apple Brandy 6/. p quart 3/0 p pint and 1/ p jill

Cyder1/3 p quart

StrongBeer 2/6 p quart

CommonBeer 1/ P quart

Vinegar2/6 p quart

AnySutler who shall be convicted before a Brigade Court Martial of having demandedmore than the above rates or of having adulterated his Liquors or made use ofDeficient Measures shall forfeit any Quantity of his Liquors not ExceedingThirty Gall! or the value thereof at the forgoing rates, The fourth part of theLiquors or the value thereof so forfeited to be applied to the Informer and theRemainder of the Liquor to be put into the hands of the person Appointed by theBrigadier who shall deliver it out to the Non Comissf and privates of theBrigades at one Jill p man p day, If Money to be laid out in Liquors or Necessariesfor the N : Comissiond Officers & privates of the Brigade and distributedin due and equal proportions,

TheBrigade Sutler is also at Liberty to Sell leaf Tobacco at 4/ p lb.

PiggTail 7/6 p lb hard soap 2/6 p lb But noother Articles rated for the publick Market shall be sold By him or any personacting Under him on any pretence wnatever.

Sutlerswere not confined to the large camps of either army, they followed the army allthe way to the far reaches of the new United States. On the western frontier near Pittsburgh andFort Pitt was a smaller outpost who found itself the victim of someunscrupulous vendors.

Orderly Book of the EighthPennsylvania RegimentOctober, 1778 - May, 1780

“11 Oct 1778 HEAD QUARTERS, FORT McINTOSH, As some narrow-minded persons, who not regarding the good of their country, nor yet the rules of common honesty, have presumed to approach this camp, and in defiance of all order & regularity, without license, at the most exhorbitant price sold liquor to soldiers: Therefore in order to deter all persons from committing the like abuses for the future: the Col. Commt doth direct that no person whatever shall presume to sell liquor to either officer or soldier without first having obtained leave from the Commanding Officer present, or from the General...the Col. Commt doth promise to give reward of 5s pr gallon to any soldier who shall give the earliest notice of such trespassers, & the liquor so seized shall be issued to the troops."

"Orderly Book of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment" in Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio 1779-1780 (Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison), Appendix pages 431-459 [2NN109- 178]. (Numbers in [ ] refer to specific document numbers within the Draper Manuscript Collection.)

Orderly Book of the EighthPennsylvania RegimentOctober, 1778 - May, 1780

22 May 1780 - HEAD QUARTERS, PITTSBURGH, ...Whereas it has been represented to the Commandant, that soldiers are frequently found among the inhabitants of Pittsburgh much disguised in liquor, even after tatoo beating; he therefore directs that officers of the day do take with them at least two files of men from the fort guard, & at least twice a night patrol the streets & make prisoners of the soldiers found absent from their quarters after beating the tatoo - except where such soldiers have permission in writing from a field officer commandg a regt, to remain at their quarters in town & are not found in abuse of the indulgence....The officers of the day are to sieze all liquors in the possession of persons vending them to the troops or others, agreeably to form orders, & report their names in order that those tippling houses may be pulled down & destroyed."

"Orderly Book of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment" in Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio 1779-1780 (Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison), Appendix pages 431-459 [2NN109- 178]. (Numbers in [ ] refer to specific document numbers within the Draper Manuscript Collection.)

In 1782,the QMG Timothy Pickering gives the following regulations:

"Regulations for the Government ofSutlers

1st

Allthe liquors and provisions which a sutler shall expose to Sale shall be ofgood & wholesome quality & for this reason subjected to theInspection of the quarter master general, or such officer as he shall appointfor the purpose.

2d

Theprices of the articles shall be reasonable, and to prevent imposition, a listof the prices shall be posted up at his quarters.

3d

ForLiquors or other articles sold to noncommissioned officers & soldiers,artificers and waggoners, nothing shall be taken in payment but money.

4.

Nosoldier or others described in the 3d Article are to be suffered to remainTipling about a sutler's quarters.

5th.

Atthe beating of the tattoo, each sutler is to shut up his stores, and sellnothing more until after Reveillee the next morning.

6.

Eachsutler is without delay to report to the quarter master general the placewhere he fixes his quarters.

7.

Theseregulations are to be posted up by each sutler in a conspicuous place at hisquarters.

CampSept 8. 1782 Tim. Pickering

QMG"

(Timothy Pickering, "Regulations for the Governmentof Sutlers," 8 September 1782, National Archives, Numbered Record Books,vol. 84, reel 27, pp. 96-97.)

In conclusion, interpreting aSutler either British or Continental, Grand or Pettit, Man or Women can be arewarding and enjoyable endeavor. Creating a sound, well researched impression can be a challenge, yet ultimatelyworthwhile. I have presented here only asmall amount of what I and others have found, and my humble interpretation ofthat information. I take my “hobby”seriously and strive to present to the general public and my peers the bestimpression I am able to create. I findmy desire from an undying respect for those whom I try to portray, I will neverbe able to recreate their lives but I can give my all to accurately reproducewhat their lives may have been like. Iwill close with a quote form Dr. Mayer’s text:

"They were people who were not officially in the army: they made no commissioning or enlistment vows. What kept them with the army was their desire to be near loved ones, to support themselves, and/or, in some cases, to share in the adventure. This diverse company encompassed both patriots, those who embraced the cause of independence with a fervor equaling or surpassing that of any soldier, and leeches, who were there merely for personal gain. A few prostitutes. and scavengers trailed after the army, but family members, servants, and other authorized civilians outnumbered them by far.”

BRANDYN CHARLTON

Brandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 23 years. He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area. Beginning in 2020 he will bring his sutler impression to the 17th Regiment of Infantry in America as a member and follower of the Regiment.

The Necessary Evil of Sutlery

“ASutler or Suttler” in an 18th century military context has become amore common impression for many reenactors as of late. I surmise, which is true in my case, thedecision to start representing a Sutler has grown out of the realization that Ican no longer do a proper military impression be it my age or otherinfirmities. However, this does not meanwe want to move away from the “progressive” movement or would in any way, Nothold our new impression up to the rigorous standards set forth by numerousorganizations. So, what is one to do? Well if you are fortunate like I am and the military unit you belong to hasa civilian or “camp follower” branch you are in luck. The only thing now is how to justify yourpresence either in or very near a military camp. This has a bit of a gender componentinvolved. If you portray a woman incontext you can more easily attach yourself in a variety of roles, but as amale the opportunities are a bit narrower. That’s where the Sutler can fill the void. Let me say women were often Sutlers and its nota male only impression, just that it is an area I take keen interest in. Whether it be a “petit sutler” or a “Grandsutler” the ability to portray a civilian who has reason and purpose to beinside or near a military camp has sparked new interest in the topic ofSutlers’ and Suttling.

In this piece I will give my personal opinions and assumptions based on the research, share what I have found in my research, and include some research by others on the topic. This is in NO WAY an all-inclusive guide or definitive work on the subject. However, it is a start to guide others or just make them better informed so in turn they can better inform the public we interact with.

Theterm “Sutler” finds its origin in the late 16th century Dutchlanguage Soetelen – Soeteler meaning “one who does dirty work, a drudge, lowwork”. As an English noun the worddescribes a civilian provisioner to an army or post often with a shop on thepost.

Johnson, Samuel “A Dictionary of the English Language” London, 1755

SUTLER: N,f. (soetler, Dutch; sudler, German): A man that sells provisions and liquor in Camp. PUBLICAN: A man that keeps a House of General Entertainment.

Oneof the first popular uses may have been in 1599, in Shakespeare's HenryV.

“For I shall sutler be / Unto the camp, and profits will accrue” - Pistol

Sutlers were a “necessaryevil” to the armies of the 18th centuries, many if not all personswho chose this profession were looking to make a profit. The age-old idea of supply and demand playedwell in the military campaigns of the century. Although the military and/or government would supply the men with thenecessities of life they were far from all that was needed to sustain life oncampaign, or in garrison. So enters thesutler and with them enter the rules to govern these convenient stores of the18th century military.

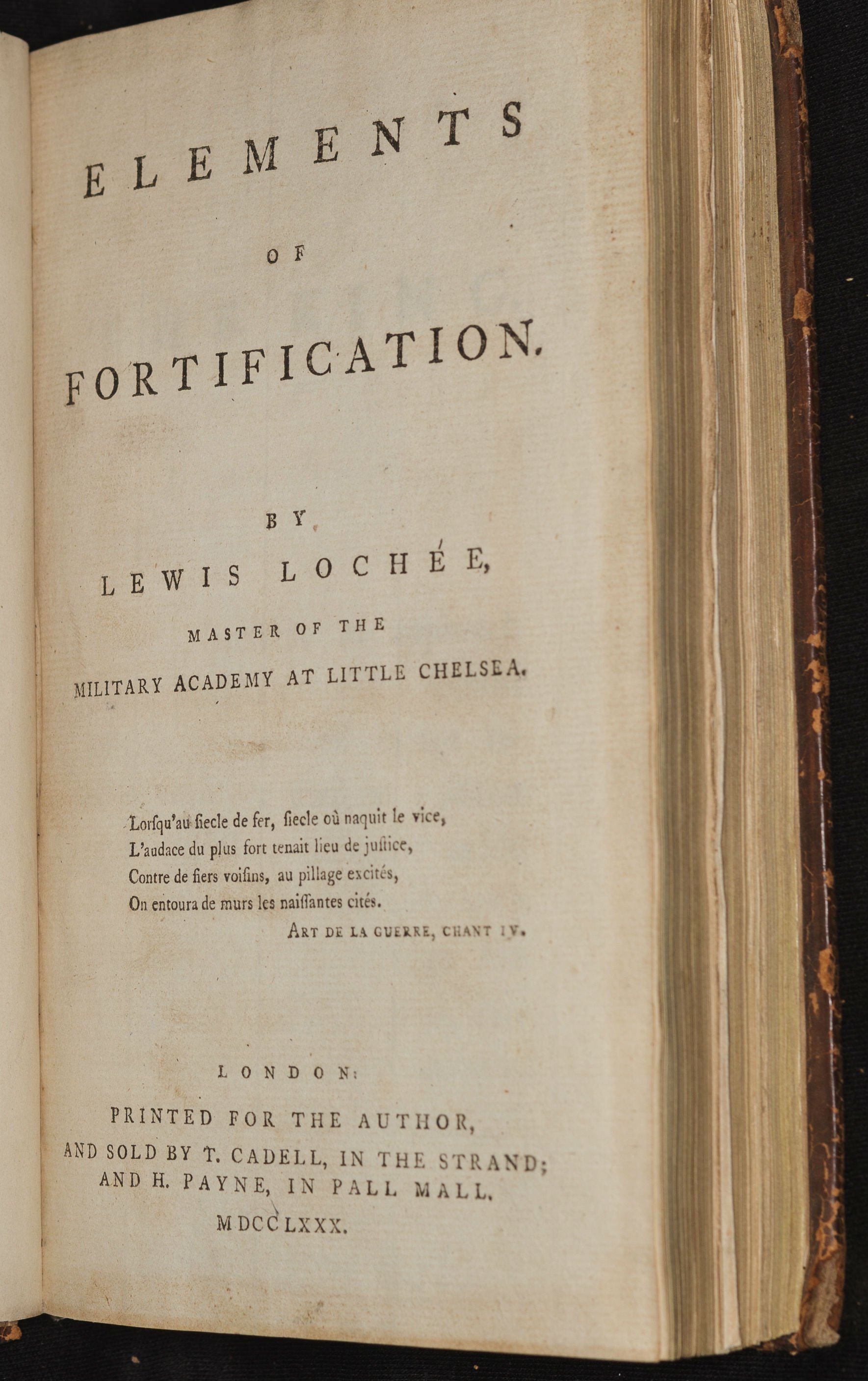

Consultation of An Essay on Castrametationby Lewis Lochee and A System of Camp-Discipline, Military Honours,Garrison-Duty, and other Regulations for the Land Forces. Collected by aGentleman of the Army, gave some very specific rules and regulations regardingthe practice. Instruction for Sutlersand location of Sutlers’ tents within an encampment are the primary focus ofmuch of the text and illustrations. An additional source for the regulation ofSutlers’ and Petit Sutlers’ for the period comes from Bland’s Treatise onMilitary Discipline. Whereinstructions are given for the layout of a proper camp including a location forthe “Grand Sutler” tent, just beyond the tents of the Batman and lying beforethe camp kitchens, and beyond the kitchens the area designated for the PetitSutlers.

From: An Essay on Castrametation by Lewis Lochee

Because I began my reenacting journey in the period of the French andIndian War, I have a strong interest in that period so naturally I began myresearch there. For a deeper look togain some context as to what the Sutler did, I chose my starting point to bethe earliest primary resource in my personal library, The Papers of HenryBouquet, Vol. II, The Forbes Expedition. Herein is just a small part of what I found.

Ina letter written from Bouquet to Forbes from Carlisle 7th June 1758describing the preparations for the upcoming campaign Bouquet writes

“The number of merchants asking to follow the army makes me think that if you offer some encouragement, you could engage workmen of useful trades, such as tailors, saddlers, gunsmiths, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, etc., to come with the army without wages and of their own accord. This would be very helpful in the woods and would save paying those people.”

Althoughthe specific term “Sutler” is not used in this example, I make the inferencethat “merchants” would include those who wish to ply the trade of Sutler to thearmy as the source of the primary requests. So much so that Bouquet thinks that offering up the opportunity to makea profit will entice others “of useful trades” to come along and save thegovernment the expense of paying for such services.

Thenext mention of Sutlers is in a letter from Bouquet to Forbes again, this timefrom Reas Town Camp, 8th August 1758. While giving his report to Forbes, Bouquetwrites:

“Yesterday I had word that three sutlers’ wagons which were going from Juniata to Fort Littleton without escort, were attacked beyond Sideling Hill by nine Indians who scalped two wagoners and took two prisoners… On hearing of the first, I sent out a party of thirteen Indians and seven volunteers to cut them off by an ambush on the Frankstown road.”

There is a lot that can belearned in this entry, first the wagons are describes as “sutlers’ wagons”which makes them civilian and not military property. Also, he notes that they were “withoutescort” making it seem a private venture, perhaps an escort would have cost thesutler and they decided it was an un-necessary expense. Something they will think of next time,provided the sutler themselves were not among the scalped or captured? We can also assume that the two posts“Juniata” and “Fort Littleton” had sutlers selling necessities to the army evenif only in passing through. Lastly, thefact Bouquet sends out a party to ambush the raiders leads me to believe thatthe sutlers were important enough to risk military forces, of course it wouldhave not been unusual for a response party to be sent out on the information araid had occurred if only to reconnoiter.

Forthe largest and most extensive piece of primary documentation I have found thusfar is the entry on 10th August, 1758 titled “RATES AND PRICES ATRAYSTOWN”.

Thecorresponding orders to produce the list I believe are found in this entry intothe Orderly Book:

8th of August, 1758:

“As it is necessary to settle the Prices of the Sutlers Goods the Commanding Officer of each Battalion or Brigade Major Shippen & Capt Young, are desired to meet at Col Burd’s Tent at 1o’Clock, who are to allow them a reasonable profit according to the different Distances for Rays Town, over the Hills & upon the Ohio – and to make their Report to the Commanding Officer.”

Tothis date using the list described as a guide, I have been able to acquireactual or a “representation” of almost all the goods listed. When I refer to a representation, I may nothave the actual quantity given in the list so I have settled for an examplei.e. “Madeira Wine” using a period wine bottle even though the quantities arelisted in gallon measurements leading me to believe they were probablydelivered in casks. I have also found some interesting items on this list thattook a little research to determine what they are. A “Vidonia” is a Dry White Wine, from theCanary Islands. Its placement on thelist gives it away as some type of wine. “Mim” I am not 1oo percent on this one, it could be a type of mixeddrink? “Tamarinds” from the tamarind tree are a pod-like fruit thatis used in cuisines around the world. Ifyou like WorcestershireSauce and HP Sauce, this fruit is found ineach. And lastly, “Gammons” are a side of bacon or the lower end of a side ofbacon.

Whilethis list is a great resource and gives idea as to what was available in 1758on the Pennsylvania/Ohio Frontier, a real gem of information is to be found inthe margin of page two. The following instructions are given:

“All Sutlers to provide Dinner & Suppers for the Officers of the Corps to which they belong, they giving in their Rations & paying 6d pr day for Cooking also Paying for what Liquors they drink.”

Thisis one of the first primary source documents to my knowledge that mentions whata sutler was doing other than the obvious selling of wares. Armed with this piece of information those ofus who search for more and more relevance for being with an army can state that(at least in 1758) sutlers were also responsible for cooking the rations of theOfficers at a rate of 6 pence per day and the said Officers were instructed topay for what they drank. This in turncan lead to many interpretive opportunities for the public; cooking,interacting with officers, serving, both food and beverages. From a vignette standpoint there can becomplaints about unpaid bills, the exchange about the quality of the food, theinteractions between officer class and either enlisted or other civilians etc.

Anotherinstance the next year in May 1759, Bouquet writes to George Stevenson, theprothonotary of York County that as it might be worthwhile to advertise

“to encourage People to carry at their own Venture several necessarys to the Army, I beg you would let me Know what Prices you think should be offered at Bedford, Ligonier, and Pittsburgh” for flour, oats, Indian corn, rye, whiskey, pork, cattle, sheep, and hogs.”

He continued that sales in camp of small items such as;

“Butter, cheese, Fowls, Fruit Vinegar Wine &c” were welcome, “but no Spirit except for the King’s Stores.”

Thenext text consulted is the Colonel Henry Bouquet Orderly Book, 17 June –15 September, 1758. The first entrydeals with military rules and regulations. On 22nd June 1758, Camp at Juniata:

“If any Suttlers, Agents of Provisions, or others have Persons to send to the Settlement, They must not leave the Camp without a Pass from the Commanding Officer-"

Onthe 24 of June orders issued from the Camp at Reas Town the Standing Ordersduring the Campaign-

“1st All Horses belonging to the Officers, Waggoners, the Train of Artillery, Sutlers, or any other Person whatsoever to be sent with the Cattle to the Pasture every morning at Revallee Beating…”

Onthe 3rd of July, from the Camp at Reas Town the order was issuedthat:

“All the Dearskins that are Actually or shall be brought into Camp are to be Delivered to the Artillery Store as soon as they are dried & stretch’d, as they are wanted to make Mockessons for the Men that go on Party’s…no Sutler or any Person whatsoever is permitted to buy any –"

Thetopic of alcohol has only been mentioned briefly up to now in this primarysource. Alcohol is a primary commoditythat Sutlers are selling and we will look specifically at that subject at thispoint. Interestingly on the 18thJuly, and again from Raes Town the order of the day begins with an order aboutthe purchase of Rum.

“No Soldier shall buy any Rum from the Suttlers without an Order in Writing from the Officer Commanding the Company, and Quantity never to exceed more than a Jill Pr Day for one Man.”

OnAugust 10th we find a Sutler being charged and brought to Courtmartial:

“A Court martial of the Line tomorrow Morning at 9 oClock to try a Suttler for selling Liquors without proper orders. – Ens. Gradon to Prosecute him.”

“26th August 1758 Camp at Rays Town

The Liquors and Goods bought from the Suttlers are to be paid at the rates fixed by the Committee of which each Corps is to take a Copy from the Brigade Major.”

Herewe have suspect evidence of some unscrupulous behaviors of the Sutlers, perhapscharging more for goods than what has been set. This example is a good one to discuss with the public about theregulation of free trade, and could be some of the seeds of rebellion? The Sutlers are looking for profit and perhapsnone were members of the “committee” that fixed the prices? They are under military regulation in orderto have access to the army, but this oversight may at times seem restrictive totheir business. The Suters are also anecessary component to having an army in the field, they supply many of theitems the army could not provide, and some items they (the army) wished theydid not. Again, on the 29th of August things have become worse andnow there is an issue with giving Liquor to the Indians, as noted with theextensive entry into the Orderly Book:

“Notwithstanding the several Orders against giving Spirituous Liquors to the Indians, many of them were drunk yesterday; The Commanding officer thinks it proper to repeat General Forbes Orders respecting it vizt .”

Oneparticular Sutler worth mentioning is Samuel Blodget, of note not so much forhis “suttling” skills but where he was and was able to do because he was aSutler serving for General Johnson’sforce on the Lake George. His famearises due to the fact he viewed the Battle of Lake George personally then drewand published The First American Battle Plan A map of the 1755 Battle ofLake George in New York, fought between the French and Native American(Iroquois) forces under the command of General Ludwig August von Dieskau, andthe British and provincial troops under Sir William Johnson. The highlydetailed pictorial view and map, depicting the “First Engagement” and the“Second Engagement”, was published barely three months after the battle, andlater re-engraved and published by Thomas Jefferys in 1756 in London. Samuel was in the Louisburg campaign of1745; was Sutler in Crown Point expedition in 1775; in 2nd expedition to CrownPoint 1757; Sutler at Ft. William Henry when Gen. Webb withdrew his troops. In1758 he rejoined the army; there as quartermaster as late as Oct. 1758.

Name: Blodgett, Samuel (1724-1807)

Title: Sutler, Crown Point Expedition

Sutler, Fort William Henry

Quartermaster, British Army

Collector of Excise, New Hampshire, 1770

Judge, Inferior Court of Common Pleas

Surveyor, Colony of New Hampshire, 1772

Member, New Hampshire Legislature, 1778

Selectman, Town of Goffstown, 1781

Presentedhere is just a small sampling of what is available for the period of the 7Years War or French and Indian War and there is much more to be discovered. The next instalment of this post will includesome observations and research pertaining to Sutlers in the period of theAmerican War for Independence.

BRANDYN CHARLTON

Brandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 23 years. He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area. Beginning in 2020 he will bring his sutler impression to the 17th Regiment of Infantry in America as a member and follower of the Regiment.

The 241st Anniversary of the Battle of Princeton: Surgeon Wardrop's Account

January 3, 2018, marks the 241st Anniversary of the Battle of Princeton, arguably the most pivotal battle in the 17th Regiment of Infantry's history. It gave them the nickname "The Heroes of Princetown," which lasted well into the 1790s if not beyond. And the engagement also sealed the legendary status of Captain William "Willie" Leslie, son of the Earl of Leven (Dr. Benjamin Rush's one-time patron). Killed in the opening exchange of fire between General Hugh Mercer's Brigade and the 17th, Leslie would be interred in Pluckemin with full military honors on January 5, 1777. His passing spurred a tremendous amount of correspondence and interest in the battle.

We see some of that interest reflected in the account of the battle below, which I transcribed at the National Archives of Scotland in the autumn of 2006. On May 21, 1777, John Belsches, a friend of the Leslie family, wrote to the Earl of Leven from Edinburgh to convey information gleaned from a visit by Surgeon Andrew Wardrop of the 17th (Edinburgh was a regular stop for returning Scottish military men). Belsches rendered the medical man's name as "Wardrobe:" a little food for thought for those of you who enjoy the idea of phonetic/accented spelling. Though Belshes had not spoken directly with Wardrop at this juncture, the information below matches what we know of the battle from other sources. Beginning with commentary of Captain Leslie's death, the dispatch provides a lengthy, albeit quick-paced, insight into the battle from a direct participant, a fitting memorial for this anniversary. It may not be a coincidence that Wardrop resigned his post in the 17th on January 31, 1777: the experience simply have have been too much for him. Wardrop had served with the regiment since July 15, 1772, and was succeeded by Surgeon's Mate John Horne (WO65/27 Army List for 1777, The National Archives of Great Britain).

National Archives of Scotland, General Deposit 26/9/513/8 John Belsches to Earl of Leven, Edinburgh 21 May 1777

National Archives of Scotland, General Deposit 26/9/513/8 John Belsches to Earl of Leven, Edinburgh 21 May 1777

"Mr. Wardrobe [Wardrop] who was Surgeon to the 17th is come here, tho’ I have not conversed with himself yet I have had every information that he can give relative to the fall of our lamented & dear friend his account exactly corresponds with what we heard before, Wardrobe was not with him but at about a hundred yards distance in the rear & could be of no service, as he no sooner received the shot than he instantly expired without a groan, the only motion he made was to give his watch to his servant, who put the body on a baggage cart & conducted it for a considerable time in spite of a very heavy fire from the Enemy but at last he was obliged to abandon it & follow the regt or must have given himself up prisoner to the provincials which wd. have served no good purpose__ Wardrobes account of the affair is that the 17 & 56 [55th Regt] were on their march from Princetown to join a detachment of the army at Trentown when they were about a mile & a half from the former the advanced guard discovered a body of Americans which tho’ superior in number Coll Mawhood had no doubt of defeating, however he went himself to reconoitre them & discovered their vast superiority in numbers wh..."

"...made him wish to retreat to the Town from whence he had come but this he found impossible as the Enemy were so near, Their was a rising ground which commanded the country about half a mile back & about a quarter of a mile off the road this he wished to gain & dress up the two regts. with 50 light horse on one flank & /50,/who were dismounted/, on the other; The Americans endeavoured [sic] also to gain the rising ground & their first Column reached one side of it rather before the two regts. got to the other, so that just when the 17th reached the top they received the fire of this column composed of about 2000 men by which all the mischief was done The 56 [55th] /who wd. not advance in a line with the 17th inspite of Coll Mawhood frequently calling out to Capt. who commanded them to mind his orders & come up/ as soon as they saw such a slaughter among the first rank of the 17th, immediately run off on their commanding officer saying it was all over with the others; The 17th returned a very well levelled fire at the provincial Colm. & instantly leaped over some rails which were [before] them & Charged them wt their bayonets [word missing from tear in letter] tho’ ten times their number almost, they ran off & retreated to the other Colms. of the rebels four in number, & consisting of 2000 men each when the provincials first fired they were about 25 paces he thinks from the 17th. & is certain they were not above 30_ Upon the whole rebel army advancing, the 17th Regt. & the 50 light horse who were mounted /&who behaved very well/ retreated as fast as possible leaving their killed & wounded, when Washington came up he assured Capt. McPherson & the other wounded that their [sic] was not a private man in that regt. but should be used like an officer on account of their gallant behavior__ The 56th [55th] run off in the greatest confusion to Princetown_ The 40th who were left to guard Prtn. never came up with the 17, Altho’ Col. Mawhood sent for them as soon as he suspected the strength of the enemy__ So far as to what relates to the 17 my paper will admit of no more----------"

For disambiguation purposes: the Captain McPherson mentioned above was Captain-Lieutenant John McPherson, who commanded the Colonel's Company. McPherson, one of three captains present with the regiment on January 3rd, was shot through the lungs and spent several months recovering behind rebel lines before being exchanged and sailing home to Edinburgh. On January 4th, he was promoted to full captain and would retire from the regiment in 1778, dying a few years thereafter. The account above greatly exaggerates the number of rebel troops involved in the battle and leaves out some significant British forces, including a battery of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and various smaller elements of units involved in the fight. Nevertheless, it provides a stunning testimony to the ferocious engagement that took place 241 years ago.

DR. WILL TATUM PhD.Will received his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

DR. WILL TATUM PhD.Will received his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Over the subsequent years, he has traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain researching the eighteenth-century British Army and used the results of those labor to improve living history interpretations. The beginning of this journey in 2001 marked the start of the current recreated 17th Infantry.

A Few Notes on Military Works in North America, 1690-1779

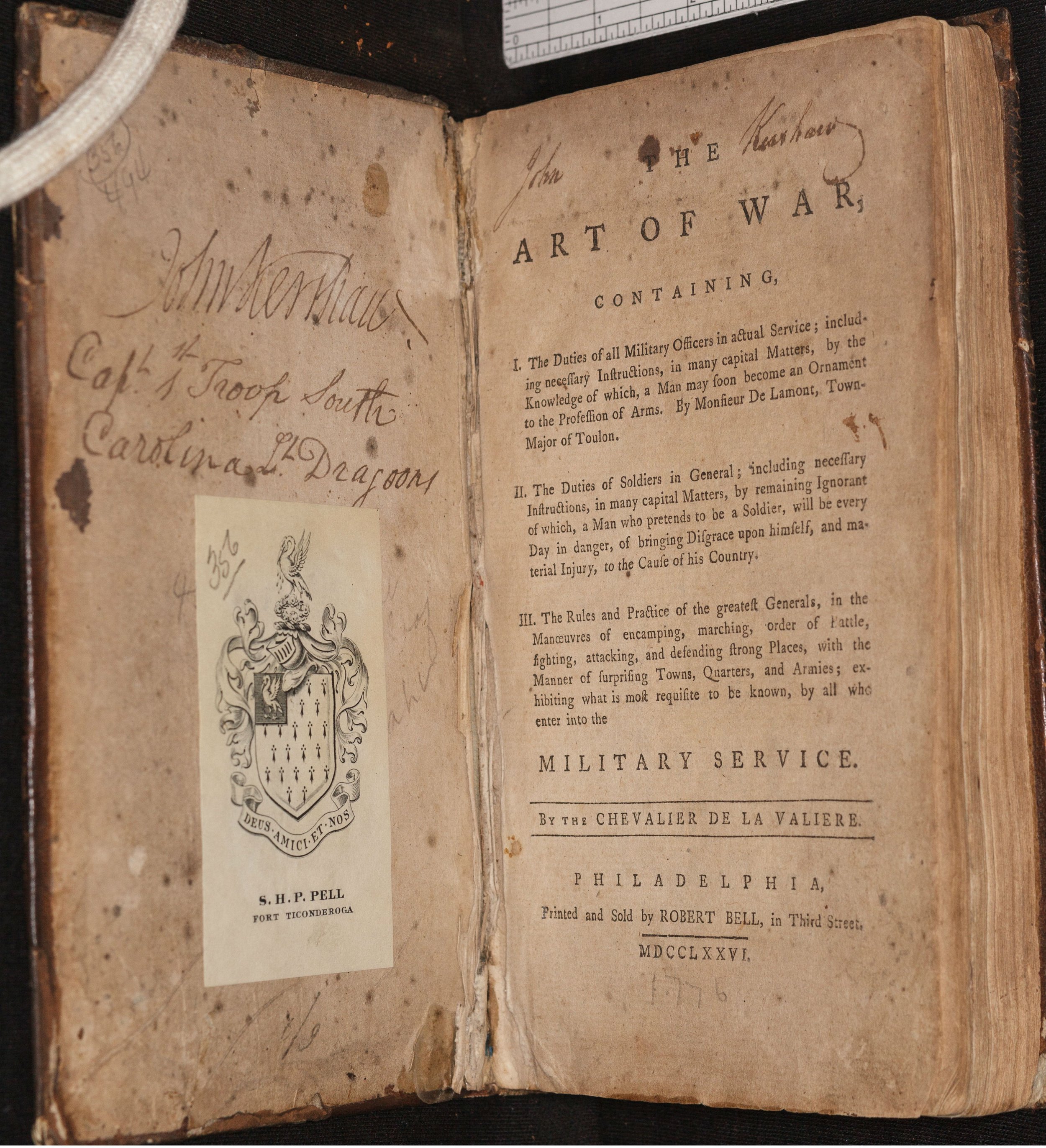

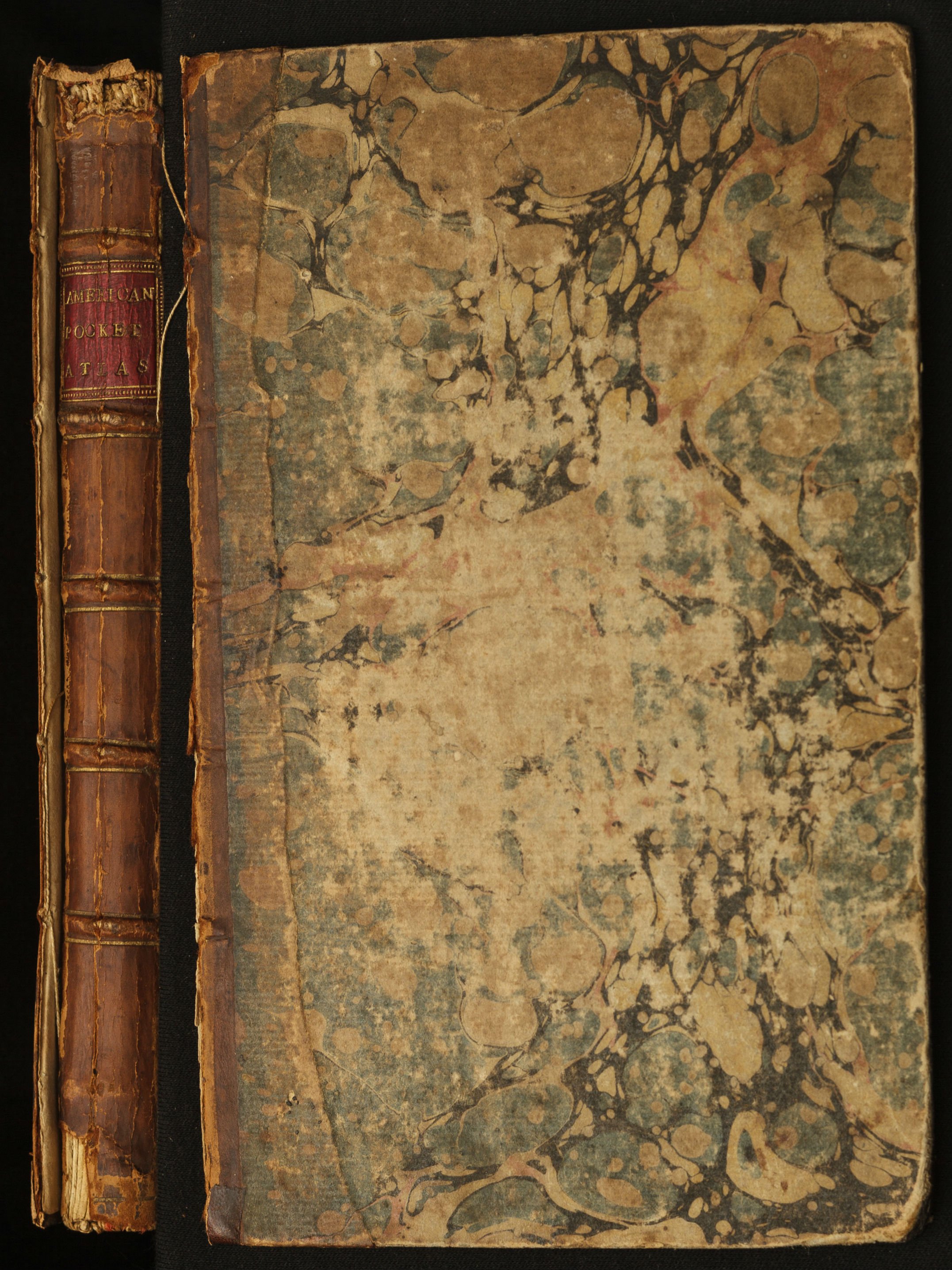

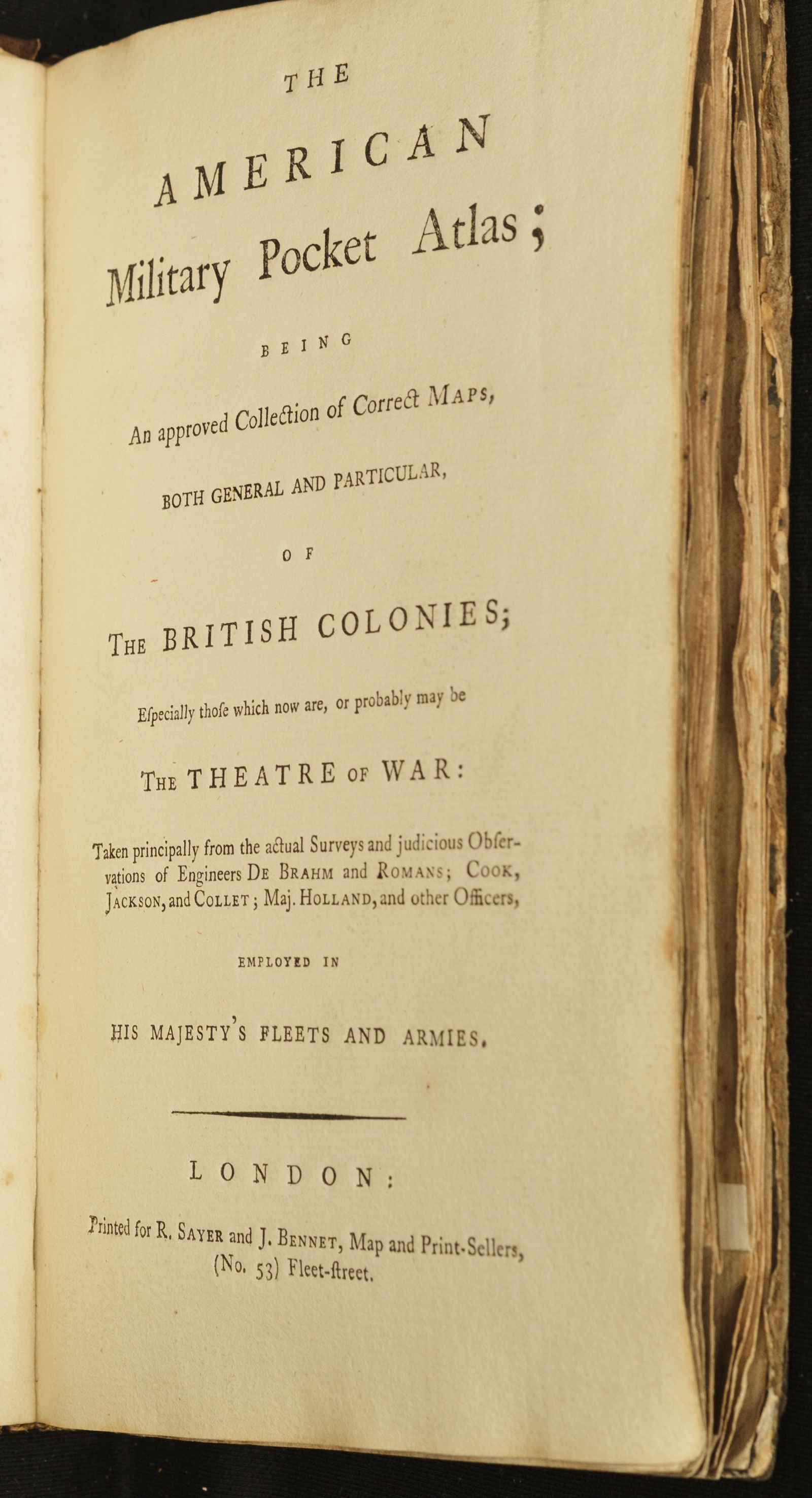

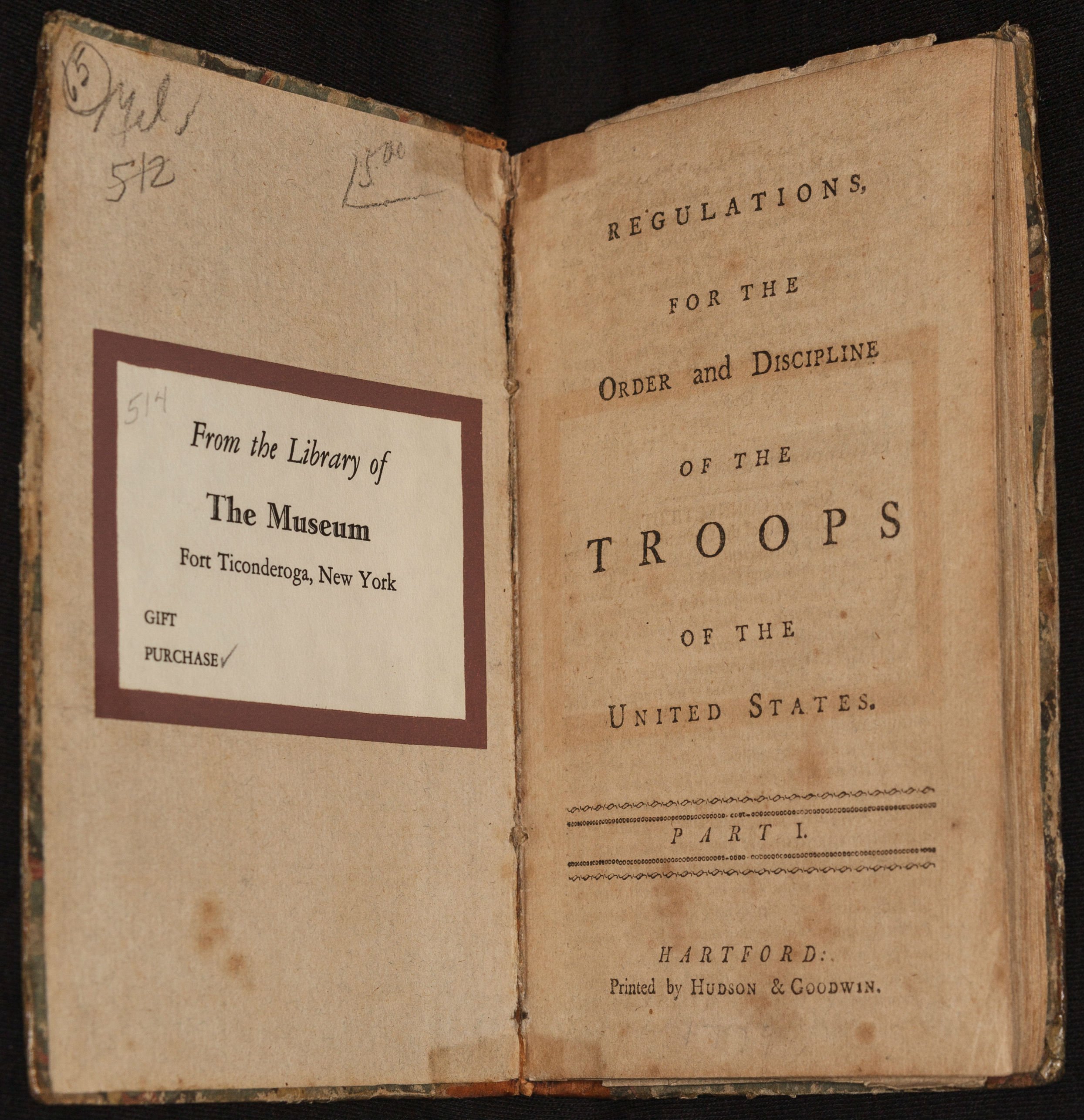

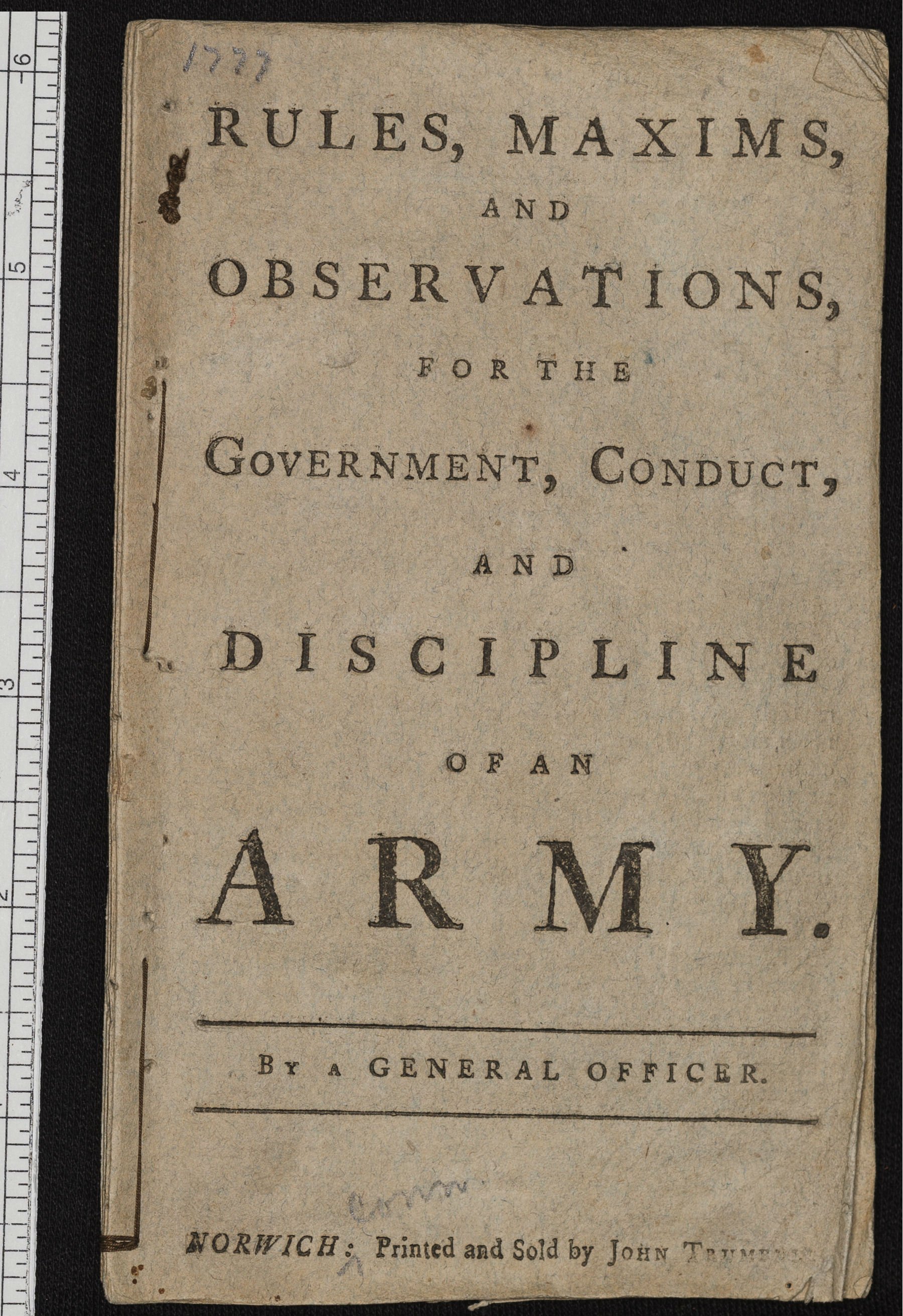

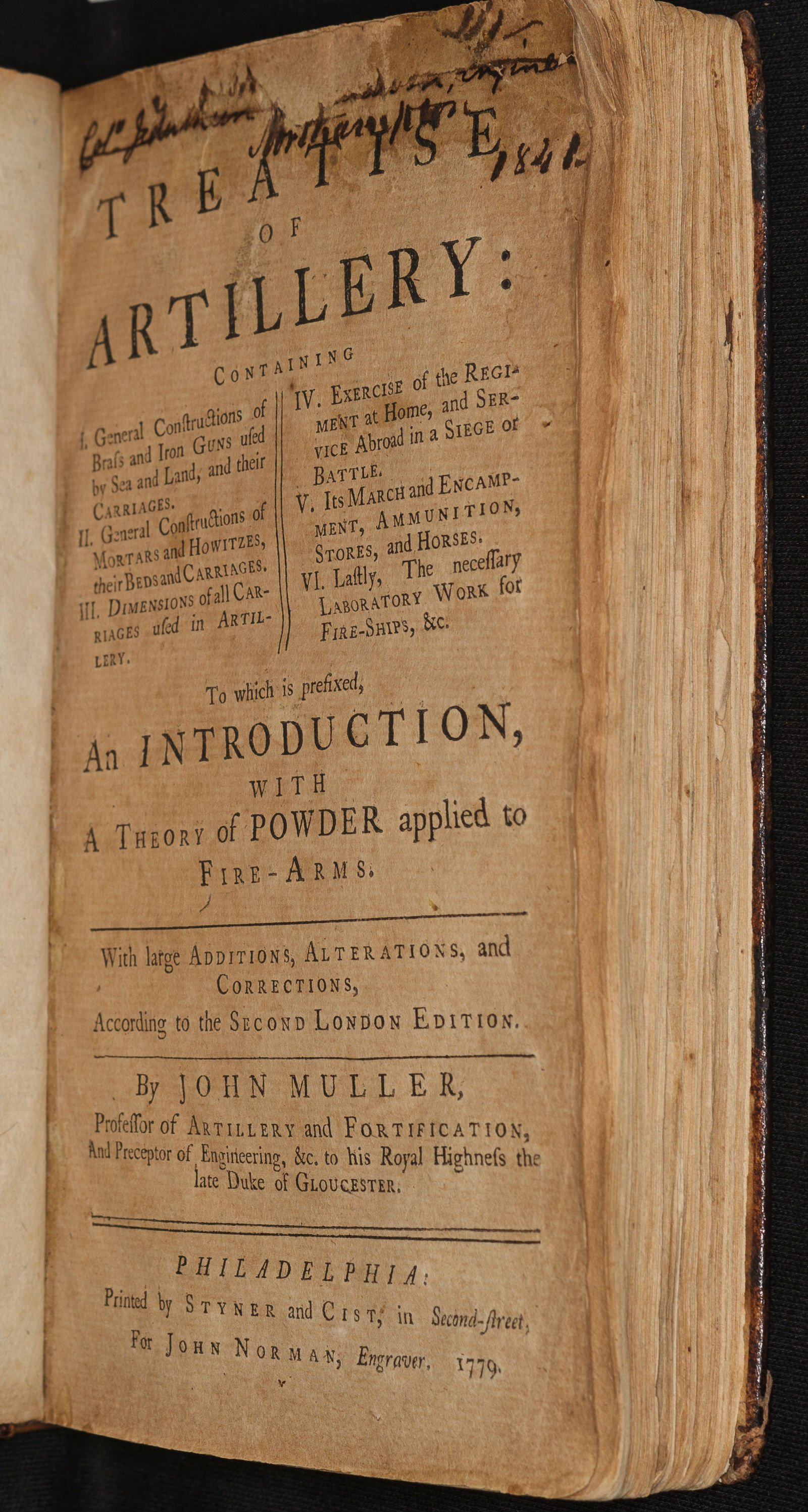

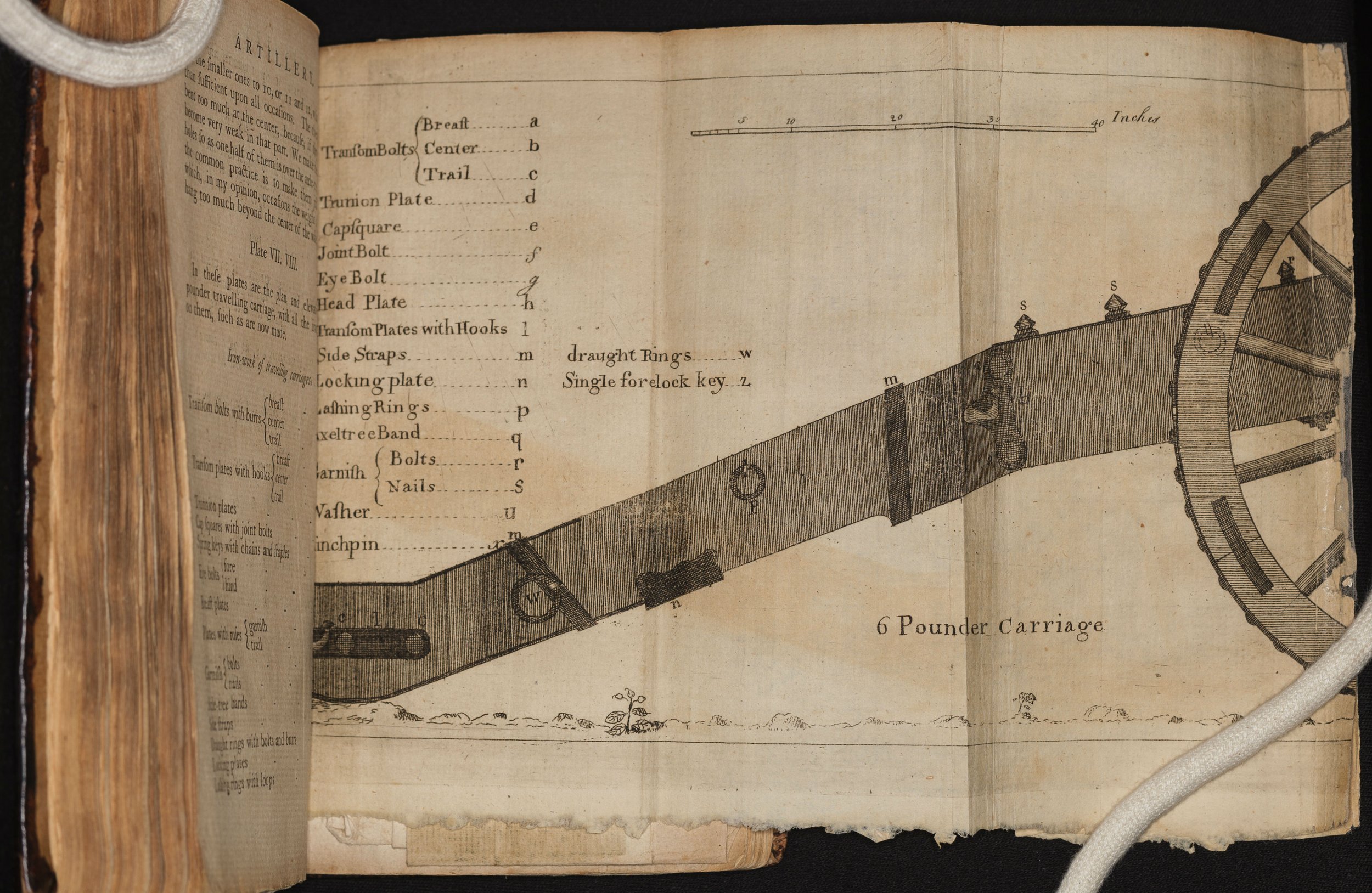

All images are of books in the collection of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum. The numbers in parentheses are the volume’s catalog number in the museum’s library. Photo credit: Robert S. Bartgis.

As early as An Abridgement of the English Military Discipline (Boston, 1690), American colonists were printing their own military titles. A number of these titles were reprints of London properties, but the colonial editions were often "enlarged" or “improved” for the needs of the local market.”[1]

Early titles were short: printed in smaller formats and often sold as pamphlets instead of bound books. They included manuals for militia drill, military dictionaries, and abstracts of longer works.

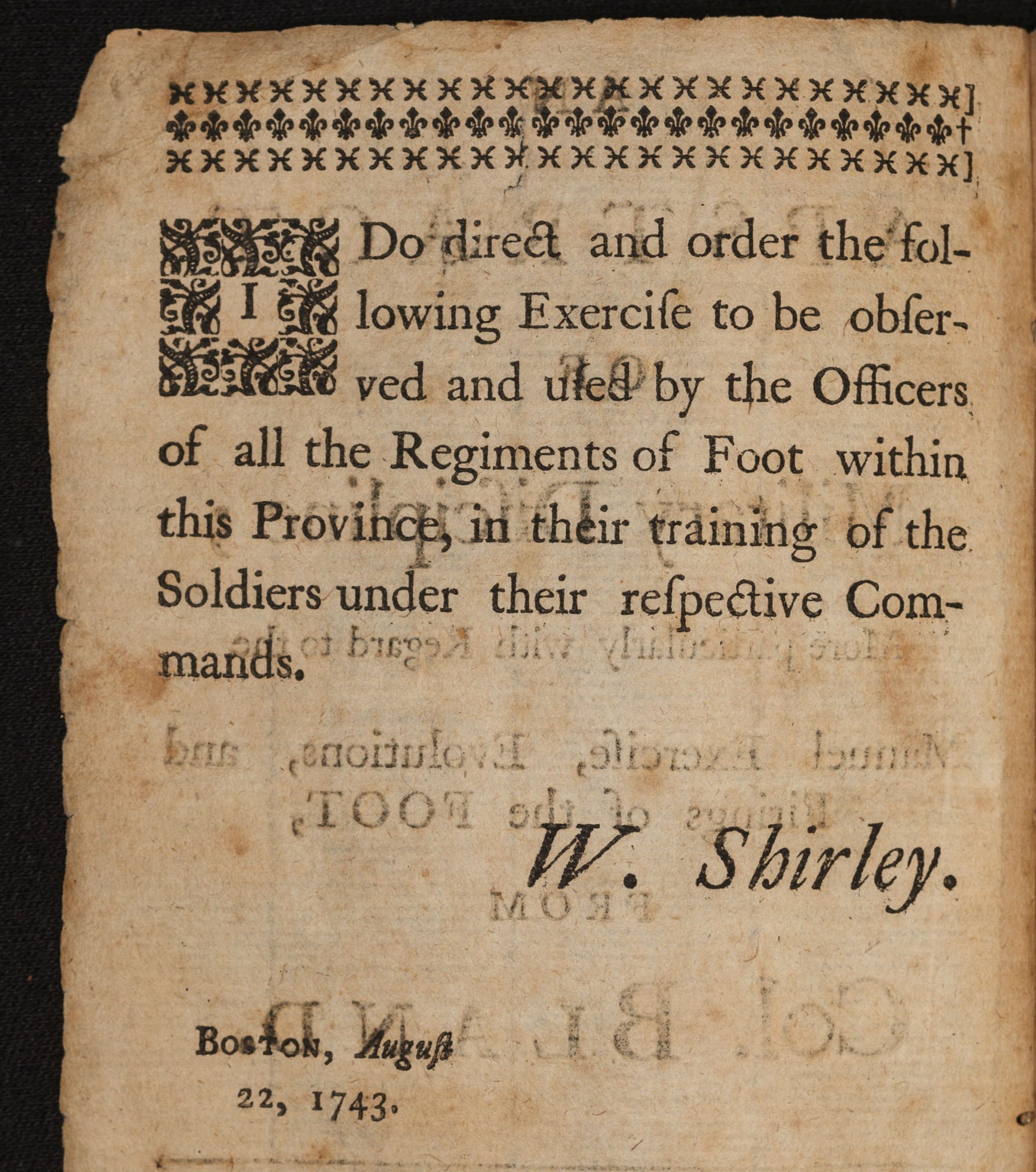

An Abstract of Military Discipline. Boston, 1755. (586)

An Abstract of Military Discipline. Boston, 1755. (586)

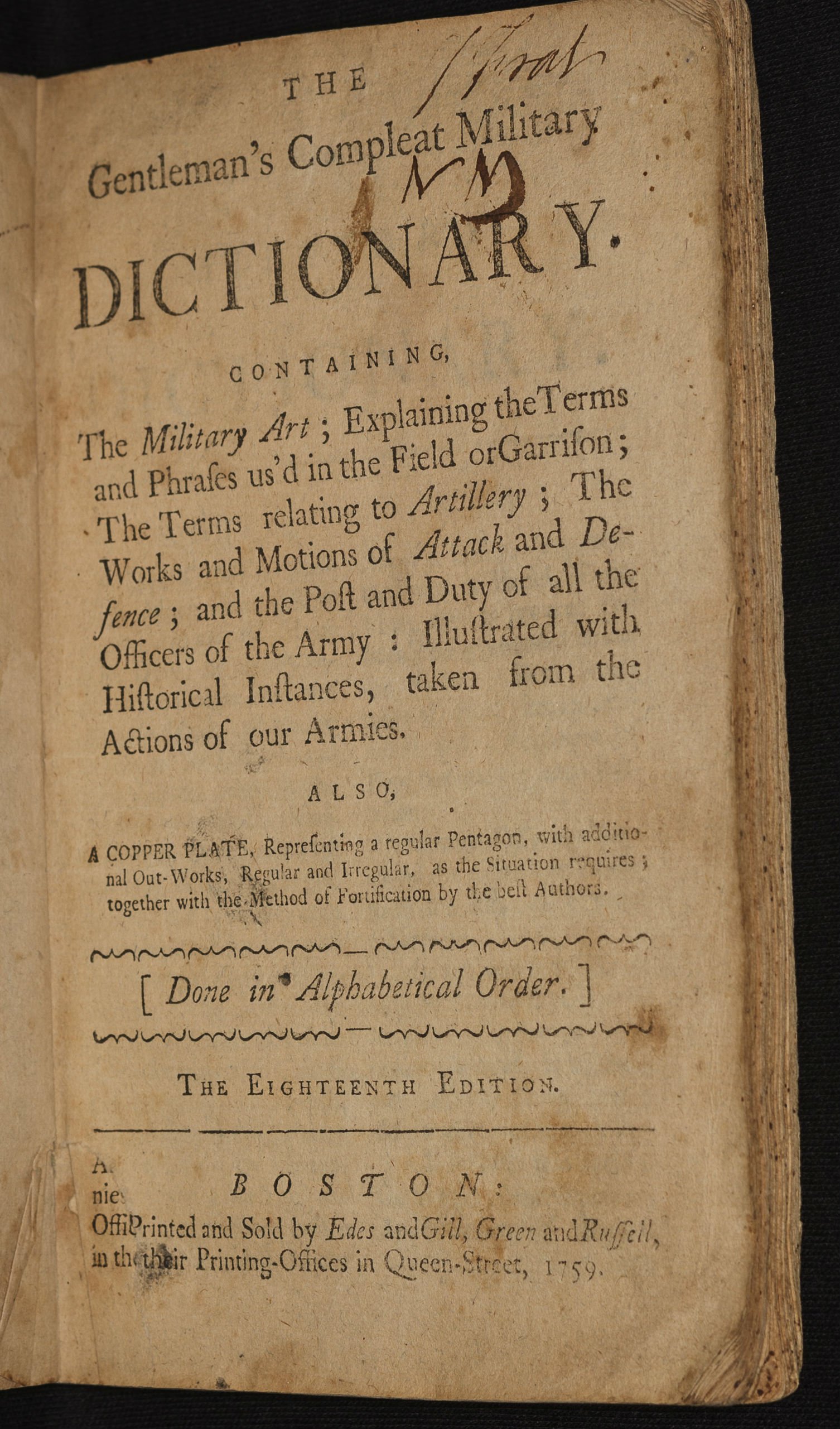

The Gentleman’s Compleat Military Dictionary. Boston, 1759 (831).

The Gentleman’s Compleat Military Dictionary. Boston, 1759 (831).

This reflected the general state of the printing market in America before the 1770s, where most printers focused on shorter works. The market books was uncertain, and many American printers lacked the capital or desire to risk publishing longer books that might languish unsold. Some exceptions were books printed by subscription, books with guaranteed buyers such as government publications of laws and edicts, and regular sellers like psalters, books of sermons, and school books.[2]

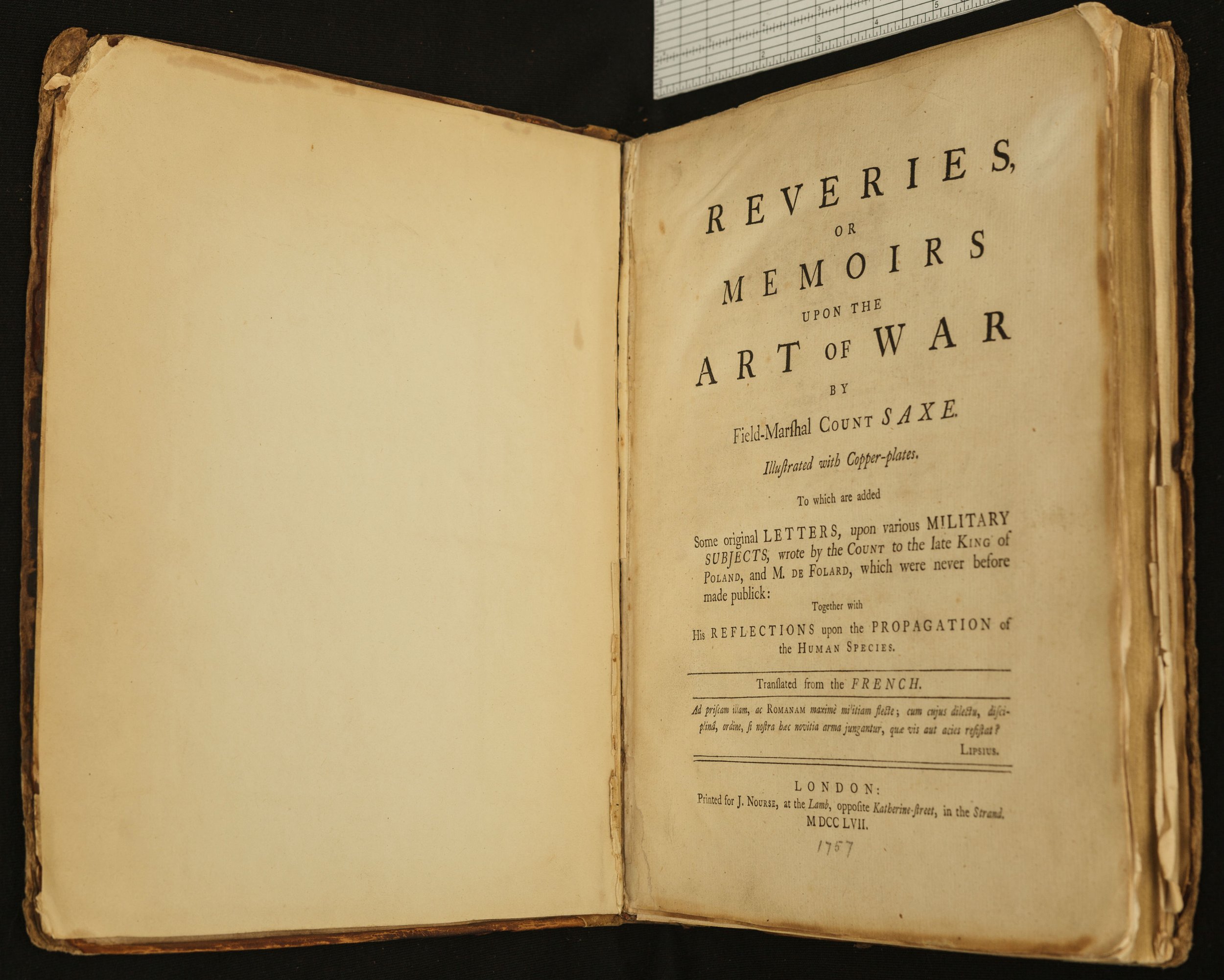

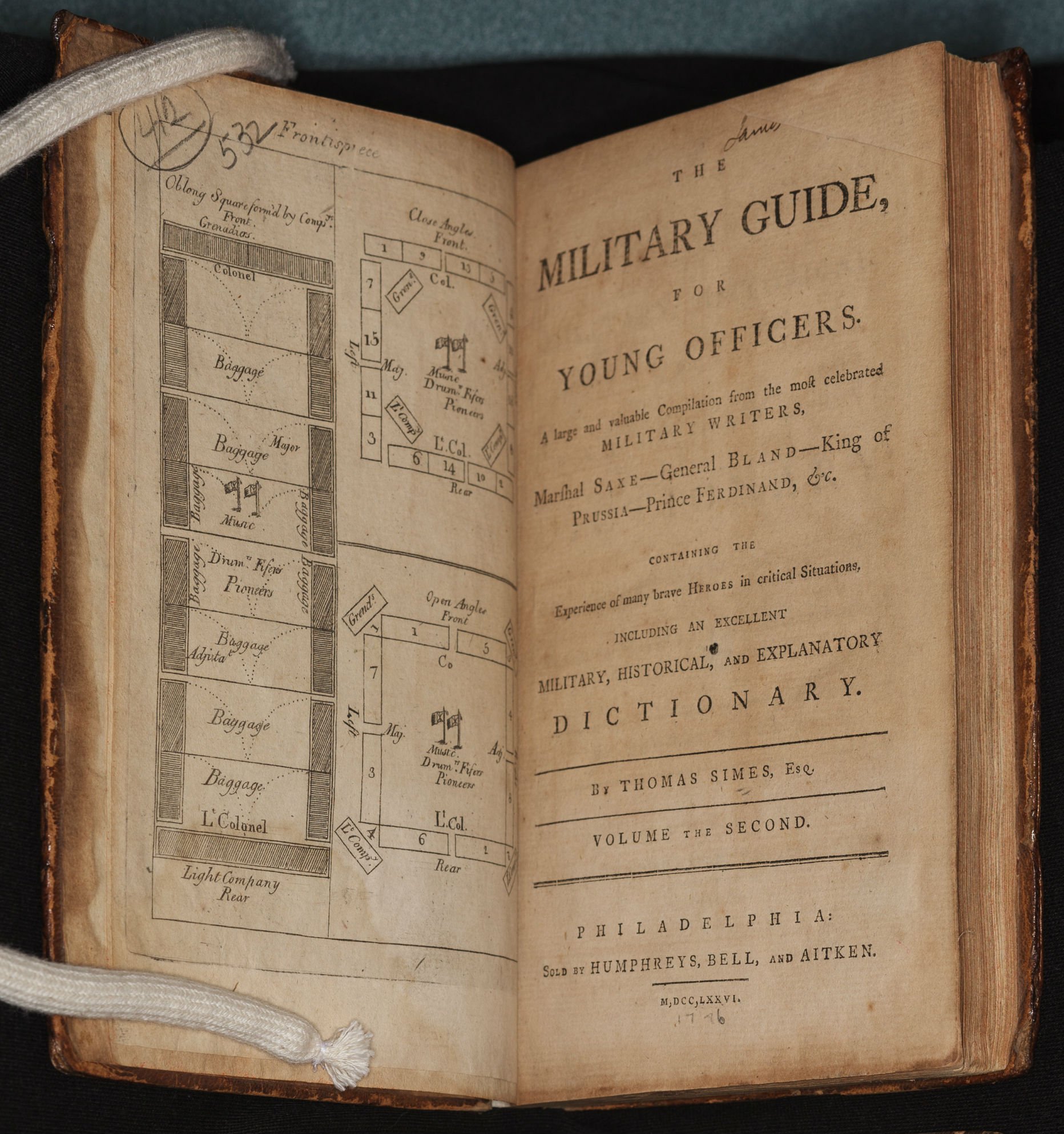

As a result, in 18th century America most longer specialty works were imported, either at the request of a buyer or by a bookseller who bought from a publisher in England and advertised the titles available.[3] Thus when the officers of the continental army and militias such as George Washington and Henry Knox educated themselves in military theory, they were usually reading London imprints of standard works by Bland, Simes, Saxe, and so on.

“As to the manual exercise, the evolutions and manoeuvres of a regiment, with other knowledge necessary to the solider, you will acquire them from those authors who have treated upon these subjects, among whom Bland (the newest edition) stands foremost; also an Essay on the Art of War; Instructions for Officers, lately published in Philadelphia; the Partisan; Young; and others.”

- George Washington to William Woodford, November 10, 1775

The status quo began to change in 1775, as the heightening of hostilities between the colonies and Great Britain created a flood of demand for military books that could not keep up with imports.

“Much of this activity was centered in Philadelphia, where more than thirty works on military subjects were published in the years 1775 and 1776 alone. Initially these books were reprints or new editions of British or European standards, but publishers quickly turned to a new generation of American military authors whose works reflected the immediacy of the war.”[4]

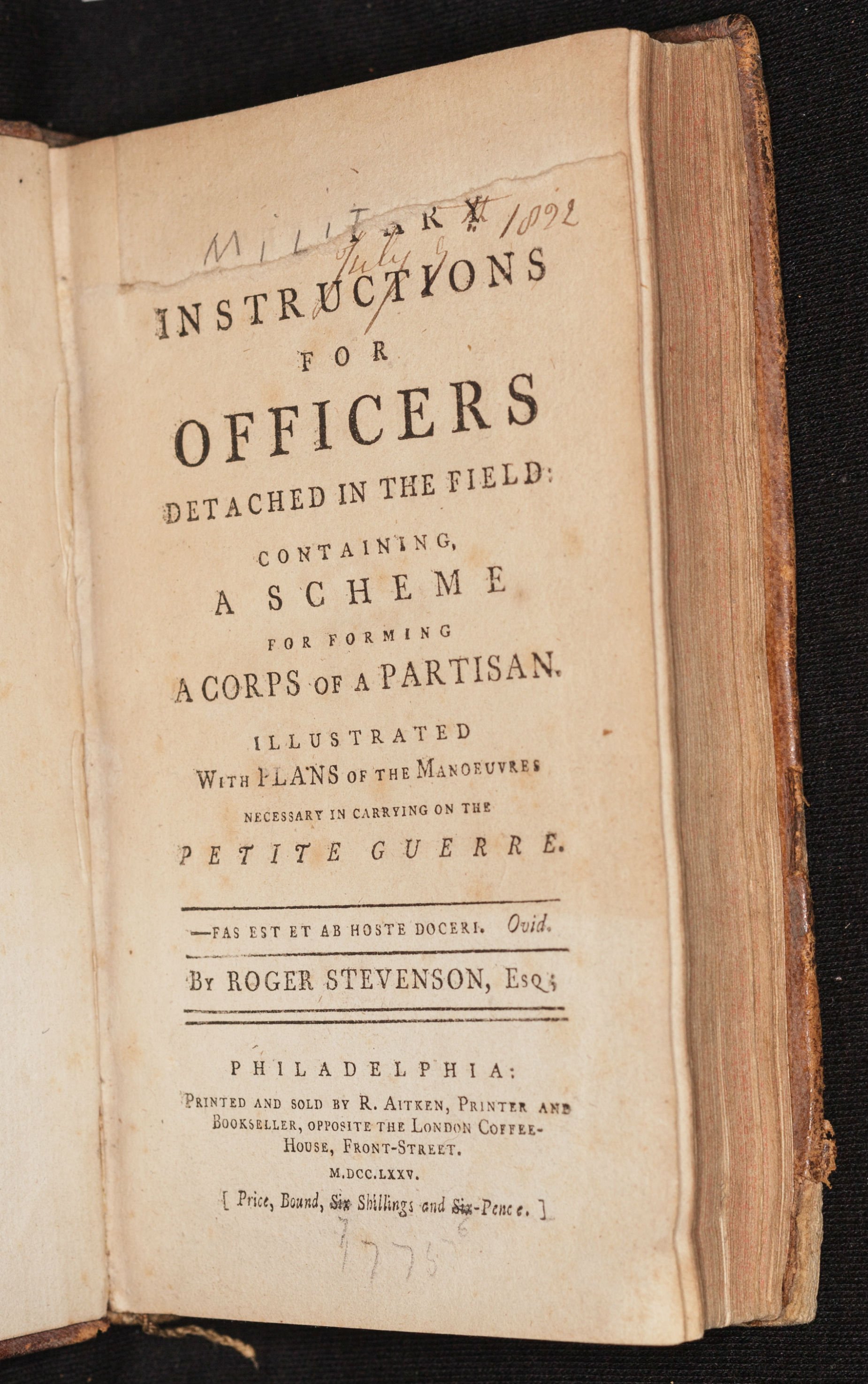

“In a country where every gentleman is a soldier, and every soldier a student in the art of war, it necessarily follows that military treatises will be considerably sought after, and attended to”, wrote Hugh Henry Ferguson in 1775, after editing the American edition of “Military Instructions for Officers Detached in the Field”, a Philadelphia publication. This book was a best-seller for the printer Robert Aitken, who collaborated with two other Philadelphia printers, James Humphreys, Jr. and Robert Bell, to spread out the cost, particularly of paper (roughly 75% of the cost), as well as the book’s copperplate illustrations.

On May 16, 1776 Henry Knox wrote to John Adams about the need for more books:

On May 16, 1776 Henry Knox wrote to John Adams about the need for more books:

“The officers of the army are very difficient [sic] in Books upon the military art which does not arise from their disinclination to read but the impossibility of procuring the Books in America; something has been done to remedy this at Philadelphia and I hope they will not stop short.”

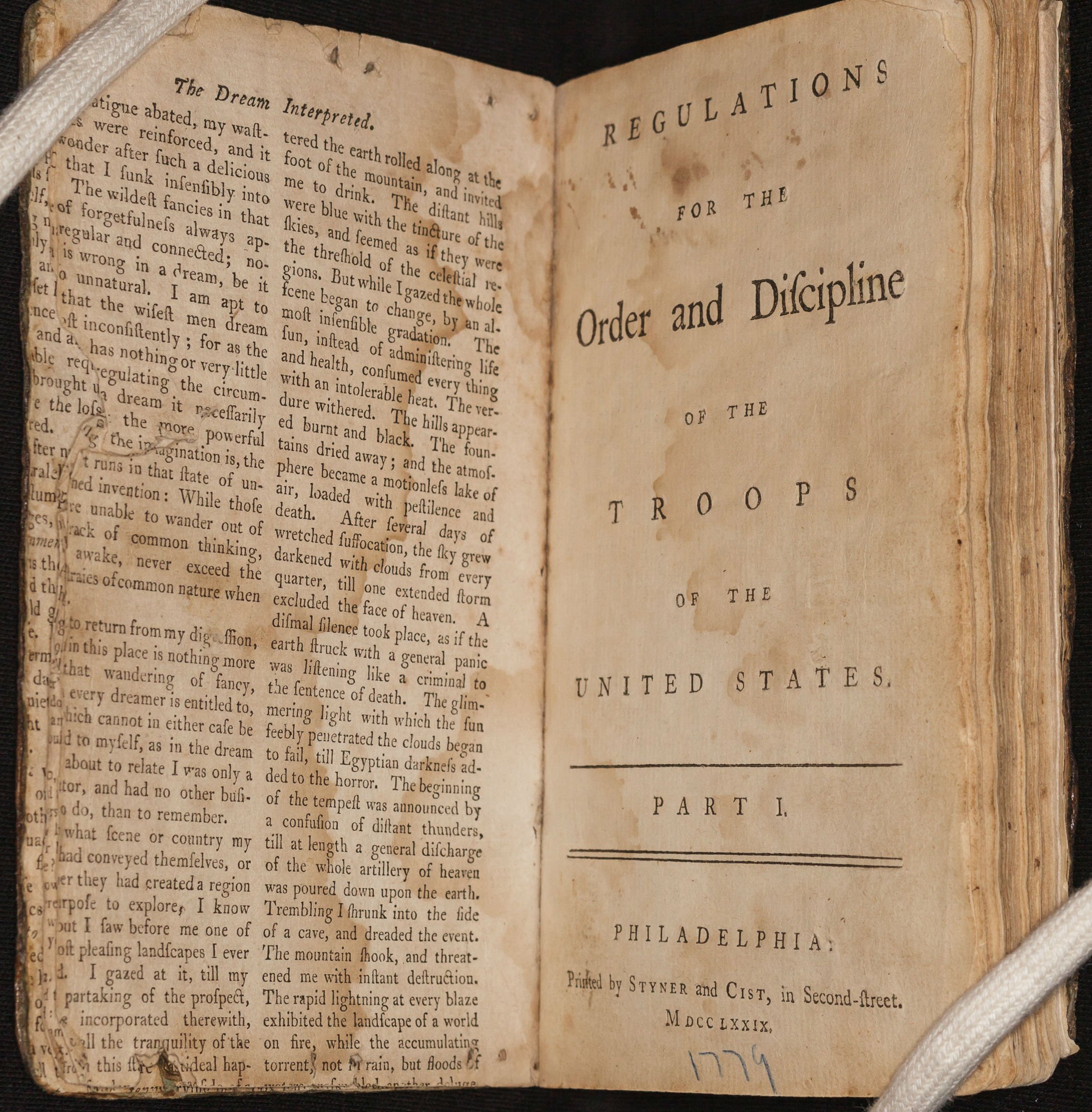

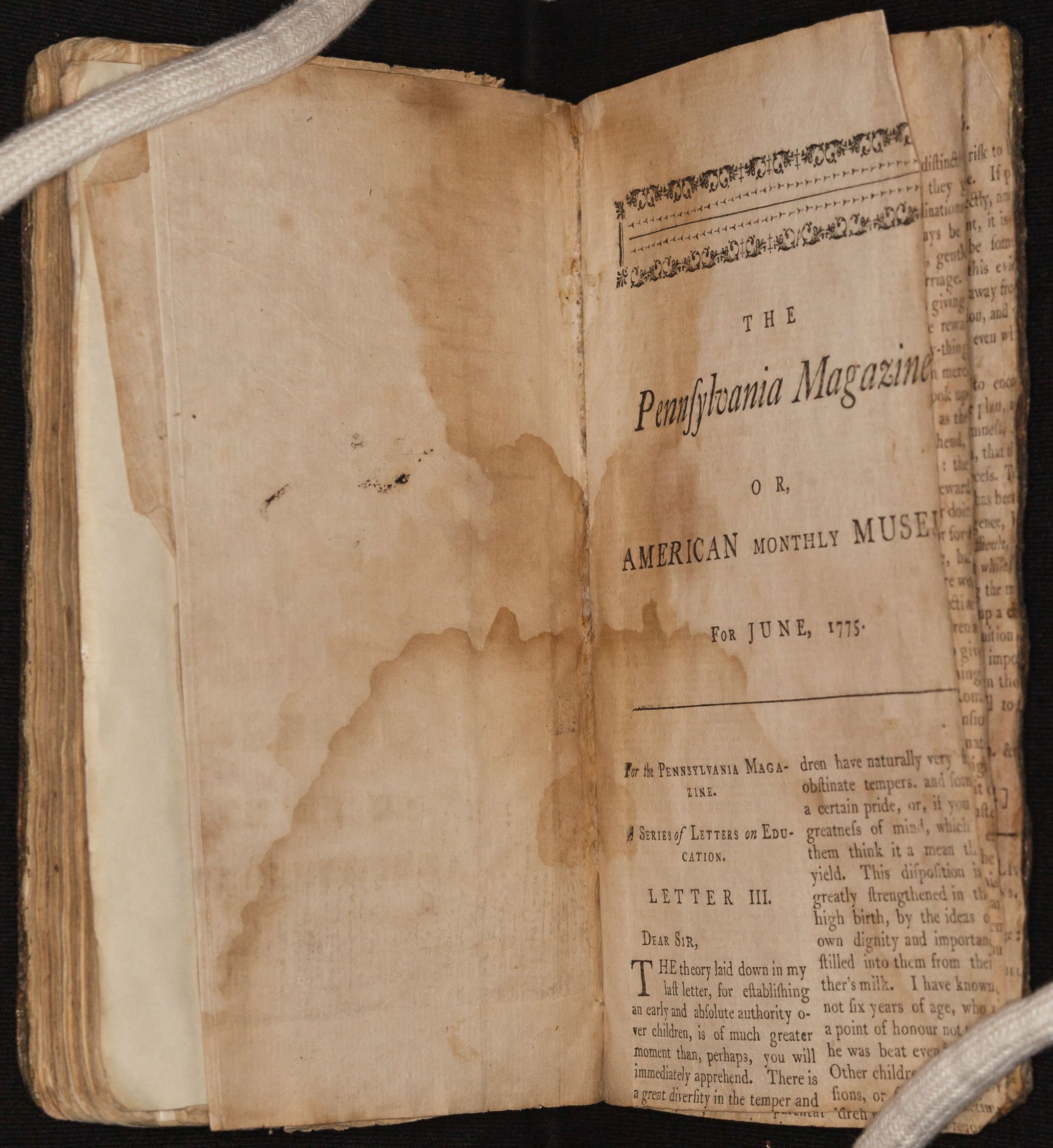

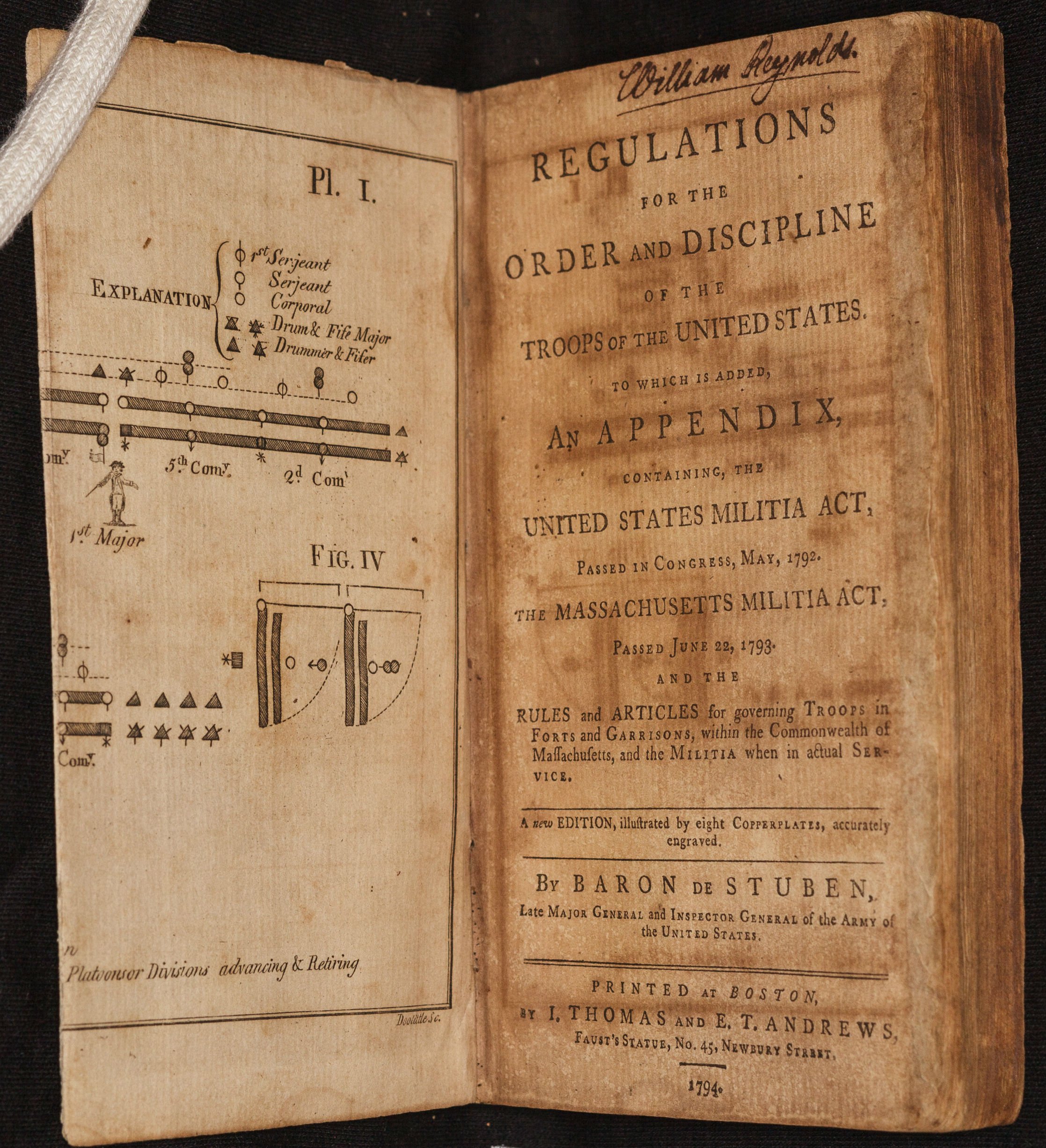

The British occupation of Philadelphia between September 1777 and June 1778 disrupted the city’s production of military works, but by 1779 another volume had appeared on the market: General Von Steuben’s “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States”. Paper was so short for the first edition that the printer used waste from the Pennsylvania Magazine for endpapers and spine linings. [5]

Surviving copies attest to the poor quality of the paper available to the printers in 1779: brown from being made from lower quality rags and brittle from ineffective attempts to whiten the paper pulp paper with lime, with a heavy impression of the laid wire screen used to form each sheet. These wartime books stand in stark contrast to the supple white text block papers and marbled paper covers of some of the elegant treatises published contemporaneously in London.

Von Steuben’s manual was reproduced throughout the course of the war, not just in Philadelphia but in other cities such as Boston, Massachusetts and Hartford, Connecticut.

Other wartime American publications included A Treatise of Artillery, and the Rules for an Army, the latter printed in Norwich, CT. Norwich had a population of about two thousand people at the time, and the printing of a manual in even so small a town demonstrates the huge demand for military literature during the war. [6]

Between imports and domestic publication at least some American officers were able to fulfill their desire for military works, since Hessian commander Johann von Ewald wrote that,

“I was sometimes astonished when American baggage fell into our hands during that war to see how every wretched knapsack in which were only a few shirts and a pair of torn breeches would be filled up with military books.”

After the end of the war Von Steuben’s Regulations would be reprinted regularly throughout the new American states, along with many other new titles for the fledgling country.

Footnotes: [1] A History of the Book in America, Volume 1: The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World, p. 85[2] Ibid, p. 156.[3] Ibid, p. 185.[4] Books in the Field: Studying the Art of War in Revolutionary America. Exhibit catalog, Society of the Cincinnati, 2017. P. 10.[5] Ibid, p. 12.[6] Phone interview with M. Keagle, 16 October 2017

BEN BARTGISBen Bartgis is a book conservator technician at a very large institution. This talk is excerpted from a presentation he gave at Ft. Ticonderoga in November 2017: "Bound for War: The Military Manual as Object in the Handpress Era".

Bands of Music in the British Army 1762-1790 Part 2

In the last post, we discussed what a band of music was and who made up their ranks. This time, we'll tackle what a band of music played and the types of duties they performed.

In part one, we learned about William Simpson, a member of the band of the 29th Regiment that deserted. Despite his absence, the band provided concerts for the public while stationed in New York and Philadelphia. In an ad in the New York Gazette, Fife Major John McLean advertised a concert for his own benefit that would not only feature the band but the drums and fifes of the regiment performing as well. [8]

The ad for his concert in Philadelphia provides more detail on what a concert from a band may have looked like.

The Concert will consist of two Acts, commencing and ending with favourite Overtures, performed by a full band of Music, with trumpets, kettledrums, and every instrument that can be introduced with propriety. The performance will be interspersed with the most pleasing and select pieces, composed by approved authors. A solo will be played on German Flute by John McLean; and the whole will conclude with an Overture composed (for the occasion) by Philip Roth, Master of the Band of Music belonging to his Majesty's Royal Regiment of North British Fusiliers. . . .after the Concert there should be a Ball; and, on this account, the music begins early. As soon as the second Act is finished, the usual arrangement will be made for dancing. [9]

In April of 1775, the Band of the 64th Regiment held a concert in Boston. A large undertaking, it combined solos, symphonic, and vocal pieces. The set list consisted of the following:

ACT 1st.

Overture Stamitz 1st.Concert German Flute,Song 'My Dear Mistress,' &cHarpsic. Concerto by Mr. SelbySimphony Artaxerexes,

ACT 2d.

Overture Stamitz 4th.Hunting Song.Solo, German Flute.Song, Oh! My Delia, &c.Solo Violin.

To conclude with a grand Military Simphony accompanied by Kettle Drums, &c. compos'd by Mr. Morgan.[10]

What is interesting to note is the absence of military music except for the final piece. Though military in nature, bands did not play only military songs. Instead, they drew from the music around them. Pieces by Stamitz, a notable German composer, and the symphony from Thomas Arne's 1729 opera Artaxerexes show that bands of music played popular music as well as songs of martial origin.

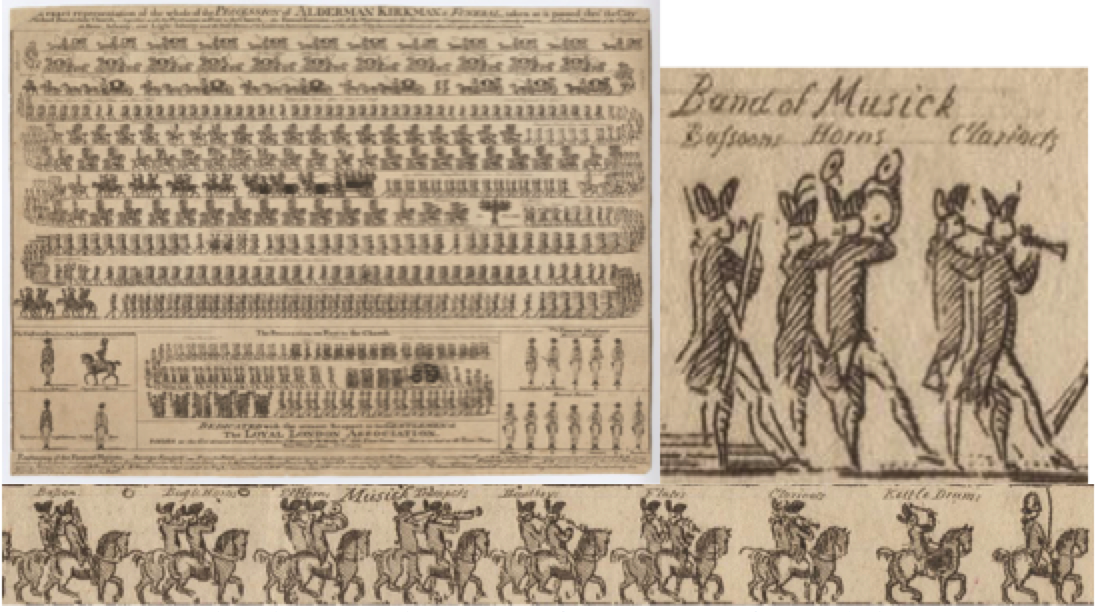

In addition to public concerts, bands also performed at military functions like funerals and ceremonies. On July 2nd, 1781, the Battalion of Loyal Volunteers of the city of New York paraded on Broadway at five in the morning. When they arrived at the house of their Lieutenant Colonel, they presented their arms, the band of music played God Save the King, and the regiment received their colours.[11]

John Rowe, a citizen in Boston, wrote on March 22nd, 1773 that he attended a funeral for his friend Captain Hay of the sloop HMS Tamar. Besides the officers and Marines, the Band of the 64th Regiment was present. Rowe remarked that "The Corps was preceded with Solemn Musick to the Chapel." On December 17th, 1774, Rowe attended a similar service for Captain Gabriel Maturin, secretary for General Gage, where the band of the 4th Regiment played.[12]

We've established the basis of bands of music, what they played, and where they played. In the next and final instalment of this series, we'll be looking at what the musicians wore.

Footnotes:[8] The New-York Gazette; and the Weekly Mercury, January 14, 1771, Page 3[9] The Pennsylvania Packet, 25 November 1771, Page 1[10] Boston Gazette, 11 April 1774. Courtesy of Don Hagist[11] New-York Gazette; and The Weekly Mercury, July 9, 1781[12] John Rowe, Anne Rowe Cunningham, and Edward Lillie Pierce, Letters and Diary of John Rowe: Boston Merchant, 1759-1762, 1764-1779, Boston, MA: W.B. Clarke Co., 1903, Pages 240-241, 288, Accessed September 3, 2017. https://archive.org/details/lettersdiaryofjo00roweRead Part 1 Here

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He’s been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

Bands of Music in the British Army 1762-1790

"The band of Musick very fine. The whole perfectly well cloathed and appointed"

On the 9th of March, 1768, Alexander Mackrabie wrote to his sister to describe his time in Philadelphia. Unfortunately for him, he writes, "at this place and at this season there is so little of anything amusing." In order to pass the time, Mr. Mackrabie described a recent practice in the city that was "extremely in vogue" called "Serenading."

We---with four or five young officers of the regiment in barracks---drink as hard as we can to keep out the cold, and about midnight sally forth, attended by the Band which consists of ten musicians, horns, clarionets, hautboys, and bassoons, march through the streets and play under the window of any lady you choose to distinguish, which they esteem a high Compliment. . . . I have been out twice and only once got a violent cold by it.[1]

Bands of Music, also known simply as bands, were another musical entity that existed in the British Army. It is at this point that a distinction must be made between drums and fifes and bands of music. Drummers and fifers were enlisted to play the drum and fife for various duties in camp, signals in battle, and other martial ceremonies. In a regiment of foot, only the grenadier company was allowed two fifers. The other companies were only officially allowed one drummer per company, with the light company typically swapping its drummer for a horn player.[2]

Instrumentation of a band varied by regiment but generally followed the German tradition of Harmoniemusik, or wind music. Typically scored for at least 6 instruments, compositions included parts for clarinets, hautboys (known today as oboes), horns, and bassoons.[3]

A roll for the musicians of the 23rd Regiment exists from 1786. The leader, or Band Master was Jacob LeCroix. Under him were 2 clarinets, 2 hautboys, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, and a timpani player. All of the men under LeCroix served in America, with the newest member of the band having served 5 years by 1786.[4]

When the band of the Royal Artillery was formed in 1762, Lieutenant-Colonel Phillips came up with Articles of Agreement. They laid out rules that most other regiments would unofficially use for their own bands.

- The band to consist of eight men. who must also be capable to play upon the violoncello, bass, violin and flute, as other common instruments.

- The regiment's musick must consist of two trumpets, two French horns, two bassoons, and four hautbois or clarinets ; these instruments to be provided by the regiment, but kept in repair by the head musician.

- The musicians will be looked upon as actual soldiers, and cannot leave the regiment without a formal discharge. The same must also behave them, according to the articles of war.

- The aforesaid musicians will be clothed by the regiment.

- [In the handwriting of Colonel Phillips.] Provided the musicians are not found to be good performers at their arrival they will be discharged, and at their own expense. This is meant to make the person who engages the musicians careful in his choice.”[5]

As seen in the Royal Artillery Articles of Agreement, bands were typically made up of private soldiers. These men would receive extra pay from the officers of a regiment to supplement their wages as well as buying instruments. The soldiers were not drummers and fifers; instead, they were known as musicians. Despite being soldiers, these men were talented professional musicians, often able to play multiple instruments. Members of the band did not play or typically fight in battle but instead fulfilled other duties, military and non-military.[6]

It was not uncommon for drummers or fifers to also be members of the band. William Simpson of the 29th Regiment deserted from New York in December of 1770. In his description, his officer wrote that Simpson

"plays well on the Flute and Fife, and plays a little on the Violin and French Horn. Had on when he went away, a short yellow Coat, fac'd Red,. . . the Coat lac'd with Drummers' Lace."

William Simpson was most likely a fifer in the 29th but because he could play multiple instruments, it is possible he was in the band. [7]

Now that we know what a band was and who their musicians were, the next post will cover the duties and repertoires of these "genteel corps of music."

Footnotes: [1] Philip France, Beata Francis, Eliza Keary, C. F. Keary, and Junius, The Francis Letters, New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1901, Pages 89-92, Accessed September 3, 2017, https://archive.org/details/cu31924088024413.[2] John Williamson, The Elements of Military Arrangement; Comprehending the Tacktick, Exercise, Manoevers, and Discipline of the British Infantry, with an Appendix, containing the substance of the principal standing Orders and Regulations for the Army, London: John Wiliamson, 1781, Page 7. Courtesy of Andrew Kirk[3] https://www.lipscomb.edu/windbandhistory/rhodeswindband_04_classical.htm[4] Sherri Rapp, British Regimental Bands of Musick: The Material Culture of Regimental Bands of Music According to Pictorial Documentation, Extant Clothing, and Written Descriptions 1750-1800, Accessed September 4, 2017, https://www.scribd.com/presentation/215381883/British-Bands-of-Musick[5] Ibid.[6] Williamson, The Elements, London: John Wiliamson, 1781, Page 7[7] The New-York Gazette or the Weekly Post-Boy, September 17, 1770, Page 4

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He's been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.

JOSHUA MASONJoshua is an undergraduate student at Rhode Island College majoring in Secondary Education and History. He's been researching fifers, drummers, and bands of music during the eighteenth century for the past 5 years.