Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

Fitted With the Greatest Exactness: A new Recruit's Uniform

I've been reenacting for a decade, and for the past few years have portrayed an 18th century American writing master, clerk, or bookbinder, roles close to my modern job as a book conservation technician. But I'd never portrayed a soldier, and with my 20s winding down I decided that now was the time to join an army unit - plus, one man who enlisted in the 17th in the 1770s gave his occupation as a bookbinder.

For my first event I visited one of the unit's tailors to make a fatigue cap and gaitered trousers, and was able to borrow everything else. I was grateful for the loaner clothes and accouterments but I’m a small man by modern standards and they were too large. After being used to wearing civilian clothes tailored to my body I noticed the difference. My loaner clothes didn't sit right and the excess fabric made it harder to move, my gear slid around when I moved quickly, my hat was in danger of flying off when I ran. There was also a psychological element to wearing an ill-fitting uniform: I felt like I was playing dress-up instead of wearing practical clothes that made me look like I belonged. Cuthbertson mentions the importance of fit in making a soldier look smart in his 1776 "System for the Complete Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry":

"As the state in which the Cloathing is usually sent to a Regiment, requires many alterations, to make it perfect, and as nothing contributes more to the good appearance of Soldiers, than having the several appointments which compose their Dress, fitted with the greatest exactness, it is necessary that no pains be spared, to accomplish so advantageous a design"... [1]

Between my first and second event I visited the unit’s tailors to make my own clothes. They drafted a pattern for me and then showed me step by step how to make a coat, waistcoat, and hat. I also received a set of my own accouterments, which were sized for my height.

[gallery ids="3579,3578,3577,3580" columns="2" size="medium"]

I noticed the difference immediately at my second event: my clothes allowed a full range of easy motion, my gear stayed in place as I ran, knelt, and threw myself to the ground without needing to be readjusted, and I felt more like a soldier. Part of that was fit, and part of it was the uniform being less forgiving than my tradesman's clothing. The snug waistcoat with layers of interfacing and wool, coat with layers of broadcloth, interfacing, and lapels stiff with lace, a new neck-stock of stiff buckram, and tightly-laced gaitered trousers changed my posture, forcing my shoulders back, my belly in, and my neck up. The 1764 Manual Exercise describes the "Position of a Soldier under Arms" in much the same fashion - no slouching over my workbench in an apron like I'm used to:

"...the Belly drawn in a little, but without constraint; the Breast a little projected ; Shoulders square to the Front, and kept back..." [2]

The end result: a newly-minted recruit of the recreated 17th. Clothes don't make the man and I have a lot of learning to do, but they certainly helped me get into the right mindset.

Footnotes: [1] Cuthbertson, Bennett. Cuthbertson's System for the Complete Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry. Bristol: Rouths and Nelson for A. Gray, Taunton, 1776. Page 67. Accessed through Google Books, 8 October 2017. [2] The manual exercise, as ordered by His Majesty, in the year 1764. Philadelphia: Humphreys, Bell, and Aitken. 1776. Page 3. Accessed through Archives.org, 8 October 2017.

BEN BARTGISIn addition to being a new recruit to the 17th, Ben Bartgis is a book conservator technician at a very large institution and teaches on the material culture of literacy in the long 18th century.

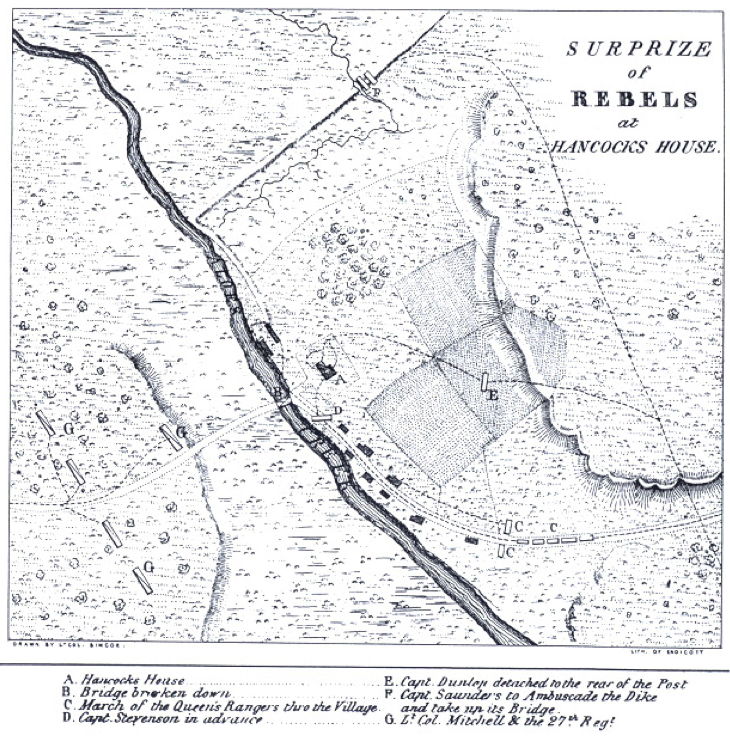

The Making of a “Massacre” Simcoe’s Surprise Attack at Hancock’s Bridge

While the British army was quartered in Philadelphia for the winter of 1777-78 foraging parties were frequently sent out to gather supplies. One such expedition was sent to Salem County, New Jersey in March of 1778. British engineer, Captain John Montressor, recorded in his journal on March 11th:

“The Roebuck removed from the wharves into the stream and the Camilla fell down the river and in the afternoon followed her a detachment of 1,000 men under the command of Col. Mawhood, 17th, 27th, and 46th Regiments, Simcoe’s Rangers.” [1]

Upon arrival to Salem on the 17th of March, Mawhood had all intentions of keeping peace with the local population and to pay for all provisions taken. Major Simcoe writes: “Colonel Mawhood had given the strictest charge against plundering…” [2] but before the expedition was over, the Queen’s Rangers would spark outrage and distain by their treatment of the local rebel militia at Quinton’s Bridge, on the 18th and at Hancock’s Bridge on the 21st. The later would be called a “massacre”.

When the British arrived and took control of the town of Salem, the local militias formed to try and impede Mawhood’s movements. The Alloway, a tidal creek of the Delaware River south of Salem, was chosen as a natural defensive line by the militia to stop the British from moving towards Bridgeton. There were three crossings over the creek: Hancock’s Bridge (closest to the Delaware), Quinton’s Bridge (in the middle) and Thompson’s bridge (furthest east), and each would be guarded.

The first skirmish between Mawhood’s force and the militia occurred on the 18th of March and involved a foraging party of the 17th Regiment of Foot and the Queen’s Rangers. The rebels were bloodied and many were killed or captured, but the defenses held because of timely reinforcements from Bridgeton. Frustrated by the resistance of the locals, Mawhood determined to attack Hancock’s Bridge and gave the task to Major Simcoe and his Rangers, with support from the 27th Regiment of Foot. Simcoe gives his account of the action:

“Colonel Mawhood determined to attack them at [Hancock’s Bridge], where, from all reports, they were assembled to near four hundred men… [The Queen’s Rangers] embarked on the 20th, at night, on board flat bottom boats… everything depended upon surprise. The enemy were nearly double his numbers... [The Rangers] land[ed] in the marshes, at the mouth the Aloes creek… after a march of two miles through marshes… they at length arrived… upon dry land. Here the corps was formed to attack… On approaching the place [Hancock’s Bridge], two sentries were discovered: two men of the light infantry followed them, and as they turned about, bayoneted them…the light infantry… reached Hancock’s house by the road and forced the front door, at the same time that Captain Dunlop… entered the back door; as it was very dark, these companies nearly attacked each other… The surprise was complete, and would have been so, had the whole of the enemy’s force been present, but, fortunately for them, they had quitted it the evening before, leaving a detachment of twenty or thirty men, all of whom were killed… Some very unfortunate circumstances happened here. Among the killed was a friend of the government… old Hancock, the owner of the house… events like these are the real miseries of war.” [3]

Though with somewhat inflated militia numbers, another defense of the Ranger’s actions comes from author James Hannay’s book History of the Queen’s Rangers:

Though with somewhat inflated militia numbers, another defense of the Ranger’s actions comes from author James Hannay’s book History of the Queen’s Rangers:

“Capt. Dunlop's and Stephenson's companies attacked those in the house with such fury that every man in it was killed. This was a lamentable occurrence and has enabled American writers to assert that these men were massacred, but it must be remembered that it was a night attack and that Simcoe's Rangers, instead of this insignificant detachment, expected to meet a force of at least 700 or 800 men, and, of course, a desperate resistance was expected.” [4]

There is still a cloud of confusion surrounding the number of militia actually present that night and how many men, including civilians, were killed. Simcoe states that “all were killed”, but other accounts maintain that there were prisoners taken. British Military Engineer, Archibald Robertson was on the expedition to Salem and recorded in his journal:

“This night [20th of March] Simcoe’s Rangers embarked in the flat boats and went round to the south side of Alloes Creek to surprise the Rebel post at Hancock’s Bridge. The Rangers got behind the Rebels. Killed 16 and took 11 prisoners.” [5]

Lt. Reuel Sayre, one of the militia members attacked at Hancock’s Bridge, recalled later:

“…they came upon us by surprise… All were killed, left for dead or taken prisoners but myself… I had one brother killed and one taken prisoner in this night affair.” [6]

The main purpose of the attack was to gain the south side of the bridge, not to put all to death and quarter was given to some. Simcoe was surprised at the lack of resistance and did not know the Rangers were attacking so few. He expected only the officers to be quartered in the Hancock House, not the entire guard. Captain Carlton Sheppard’s company militia was the only one stationed at the bridge, and was quickly overpowered. When the attack was finished, Simcoe laid the planks down over the bridge in order to confer with Lt. Col. Mitchell of the 27th Regiment, waiting on the other side of the creek, as what to do next:

“Major Simcoe communicated to Colonel Mitchell, that the enemy were at Quinton’s Bridge; that he had good guides to conduct them thither by a private road, that the possession of Hancock’s house secured a retreat. Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell said, that his regiment was much fatigued by the cold, and that he would return to Salem as soon as the troops joined. The ambuscades were of course withdrawn, and the Queen’s Rangers were forming to pass the bridge, when a rebel patrol passed where an ambuscade had been, and discovering the corps, galloped back. Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell… being informed of the enemy’s patrol, it was thought best to return [to Salem].” [7]

Though the Queen’s Rangers were successful, they again gave up the south side of the Alloway Creek. The outcome of the attack had a demoralizing effect on the militia. When word spread of the affair at Hancock’s Bridge, the resolve to continue a defense at the Alloway dissolved. Colonels Hand and Holme of the militia wrote Governor Livingston:

“We have made our stand on Alloways Creek… but last night the enemy landed out of their boats… and surrounded our guard at Hancock’s Bridge and took and killed almost all of them… we fear they will advance over all these lower counties… we find our numbers at present are not large enough to make a proper stand against them…” [8]

The militia moved south nearly 18 miles to Cumberland County and made the Cohansey River their new defensive line, leaving all of Salem County open to British foraging. After 6 more days of collecting supplies, the British embarked on their ships on the 27th of March and headed back to Philadelphia. The scars left on the inhabitants of Salem County were not easily forgotten. The Hancock House “Massacre” became a rallying cry and may have helped bolster Washington’s ranks in the spring of 1778:

“The nightmare of sanguinary warfare cause by the affairs at Quinton and Hancock’s Bridge produced one effect… the ire of the local militia had been excited because the raiders had escaped practically free of any kind of punishment. As matters of patriotism and retaliation the militia began to enlist in increasing numbers in the State and Continental Army troops.” [10]

One story passed down through history demonstrates the lasting resentment that formed due to Simcoe’s attack at Hancock’s Bridge and the “massacre” that occurred there:

“Later Judge Hancock’s son and a Mr. Sayer, whose father had been killed in the massacre, traveled to Philadelphia by water. They were standing on the wharf talking with two strange men when Sayer fell overboard. One of the strangers jumped in and rescued him. Mr. Sayer asked, ‘To whom am I indebted for saving my life?’ When the man told him he was the son of Colonel Mawhood, Sayer said, ‘I’ll be damned if I’ll be saved by the son of the murderer of my father!’ and jumped in the river again. He was rescued with difficulty.” [11]

It seems that Colonel Mawhood and Major Simcoe will forever be associated with the Hancock House “massacre”, deserved or not.

Footnotes:[1] Frank H. Stewart, Salem County in the Revolution (Salem: Salem County Historical Society, 1967) 45-47.[2] John G. Simcoe, John G. Simcoe’s Military Journal (Cranbury: The Scholar’s Bookshelf, 2005) 46.[3] Simcoe, Military Journal, 50-52.[4] Donald J. Gara, The Queen's American Rangers (Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2015) 116-118.[5] Ibid., 141.[6] Stewart, Salem County in the Revolution, 63[7] Ibid., 61.[8] Simcoe, Military Journal, 53.[9] Stewart, Salem County in the Revolution, 65.[10] Ibid., 86.[11] Irene Y. Hancock, In the Shade of the Old Oak (Salem: Salem County Historical Society, 1964) 15.

WILLIAM MICHELWilliam is a member of the 17th Regiment. He has volunteered and worked at several historic sites, including Valley Forge National Park, Graeme Park, Monmouth Battlefield State Park and is the current historian at the Hancock House State Historic Site in Salem County, NJ.

WILLIAM MICHELWilliam is a member of the 17th Regiment. He has volunteered and worked at several historic sites, including Valley Forge National Park, Graeme Park, Monmouth Battlefield State Park and is the current historian at the Hancock House State Historic Site in Salem County, NJ.

The Hancock House is located in Southern New Jersey. The historic site plans to host an event in Mid March of 2018 to commemorate the massacre. More information is coming soon.

Sewing Parties and Getting Things Done.

From the very first sewing party, January 2015.At this particular sewing party this weekend, we focused on trousers for new members and loaner gear trousers. The followers also worked on stays, caps, and setting up our camp-life page for the website. More to come, so be on the look out!Below are some pictures from the weekend. Enjoy!

From the very first sewing party, January 2015.At this particular sewing party this weekend, we focused on trousers for new members and loaner gear trousers. The followers also worked on stays, caps, and setting up our camp-life page for the website. More to come, so be on the look out!Below are some pictures from the weekend. Enjoy!

Battle of Princeton and the Ravages of Princetown.

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography.Princeton is a particularly special and important event for the 17th. Historically, the Battle of Princeton is “our battle”. HM 17th of Foot actually received the honor of having an unbroken laurel wreath added to their insignia as a result of their courageous efforts at Princeton. As such, Princeton has become an annual event for us. Every year we recreate the battle, complete with a battlefield tour led by Dr. Will Tatum. This year, the tour and reenactment was January 8, 2017, just days after the 240th anniversary of the battle on that very spot.

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography.Princeton is a particularly special and important event for the 17th. Historically, the Battle of Princeton is “our battle”. HM 17th of Foot actually received the honor of having an unbroken laurel wreath added to their insignia as a result of their courageous efforts at Princeton. As such, Princeton has become an annual event for us. Every year we recreate the battle, complete with a battlefield tour led by Dr. Will Tatum. This year, the tour and reenactment was January 8, 2017, just days after the 240th anniversary of the battle on that very spot. Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography Photo by Steve AlpertThere are accounts from the actual Battle of Princeton that the 17th Regiment of Foot continued to fight even against impossible odds. They “deliberately pulled off their knapsacks and gave 3 cheers, then broke through the Rebels, faced about, attacked and broke through them a second time.” (from William M. Dwyer’s “The Day is Ours”). That's a quote from someone at the actual battle. With primary sources like that, what else would you expect from a progressive unit? Using these accounts, HM 17th Regt of Foot completed knapsacks for every member who attended the Battle of Princeton this year. We also made leggings, based on accounts of what the 17th wore on January 3, 1777. It was amazing to be moving over the same ground that was actually fought over 240 years ago!

Photo by Steve AlpertThere are accounts from the actual Battle of Princeton that the 17th Regiment of Foot continued to fight even against impossible odds. They “deliberately pulled off their knapsacks and gave 3 cheers, then broke through the Rebels, faced about, attacked and broke through them a second time.” (from William M. Dwyer’s “The Day is Ours”). That's a quote from someone at the actual battle. With primary sources like that, what else would you expect from a progressive unit? Using these accounts, HM 17th Regt of Foot completed knapsacks for every member who attended the Battle of Princeton this year. We also made leggings, based on accounts of what the 17th wore on January 3, 1777. It was amazing to be moving over the same ground that was actually fought over 240 years ago! Painting on L features HM 17th Regt of Foot at Princeton. Photo on Right by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography. Put together by Andrew Kirk.However, this year, we took the event a step further. In addition to the Battlefield tour and battle reenactment, the 17th was actually in Princeton the day before, January 7. Our HQ was Morven Museum and we invited the public to see the “Ravages of Princeton”.

Painting on L features HM 17th Regt of Foot at Princeton. Photo on Right by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography. Put together by Andrew Kirk.However, this year, we took the event a step further. In addition to the Battlefield tour and battle reenactment, the 17th was actually in Princeton the day before, January 7. Our HQ was Morven Museum and we invited the public to see the “Ravages of Princeton”.  Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography Our purpose was to show the public what it was actually like for civilians and townfolk when British troops occupied Princeton prior to the battle. In Palmer Square, local townspeople were “strongly encouraged” to take the Loyalty Oath, administered by Captain Tatum. Some still chose to refuse. They were Quakers. They were women. They did not see why they would have to take the Oath. Others willingly signed and swore loyalty to their rightful King, like this wise young lad.

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography Our purpose was to show the public what it was actually like for civilians and townfolk when British troops occupied Princeton prior to the battle. In Palmer Square, local townspeople were “strongly encouraged” to take the Loyalty Oath, administered by Captain Tatum. Some still chose to refuse. They were Quakers. They were women. They did not see why they would have to take the Oath. Others willingly signed and swore loyalty to their rightful King, like this wise young lad. Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography.After administering the Loyalty Oath, the group gathered to warm up around the fire, show the public some Musket Drills, and lunch.

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photography.After administering the Loyalty Oath, the group gathered to warm up around the fire, show the public some Musket Drills, and lunch.

Lunch at Morven. 17th members gathered around the fire, and yours truly enjoying lunch. Photos by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography Later, some of our members went rogue. Accounts abound of looting, Pillaging, and other ravages by soldiers on both sides of the American Revolution. As such, no event entitled “Ravages at Princeton” would be complete without a little bad behavior. Several innocent bystanders were brutally robbed by civilians, drunken soldiers, and even our own camp followers. There’s also reports that Captain Tatum was even assaulted by a certain camp follower, with a lettuce no less!

Lunch at Morven. 17th members gathered around the fire, and yours truly enjoying lunch. Photos by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus Photography Later, some of our members went rogue. Accounts abound of looting, Pillaging, and other ravages by soldiers on both sides of the American Revolution. As such, no event entitled “Ravages at Princeton” would be complete without a little bad behavior. Several innocent bystanders were brutally robbed by civilians, drunken soldiers, and even our own camp followers. There’s also reports that Captain Tatum was even assaulted by a certain camp follower, with a lettuce no less! Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photographyThankfully, all the “nasty pieces of baggage” were arrested and court-martialed. Some were given lashes. Others escaped justice due to contradictory testimony and lack of evidence. One camp follower made the mistake of proudly claiming she was a loyal British subject and therefore should be entitled to the belongings of the local populace who would not take the Oath. When she was reminded of the lettuce incident, she was quickly drummed out of camp and her marriage dissolved. Note - all of the "sentences" are actually based in historical fact.

Photo by Wilson Freeman, Driftingfocus photographyThankfully, all the “nasty pieces of baggage” were arrested and court-martialed. Some were given lashes. Others escaped justice due to contradictory testimony and lack of evidence. One camp follower made the mistake of proudly claiming she was a loyal British subject and therefore should be entitled to the belongings of the local populace who would not take the Oath. When she was reminded of the lettuce incident, she was quickly drummed out of camp and her marriage dissolved. Note - all of the "sentences" are actually based in historical fact.

Photo by Richard Patterson, the Old Barracks Museum, TrentonThis amazing group of guys survived sub-freezing temperatures and 5 inches of snow to march 14 miles in the middle of the night from Trenton to Princeton. They followed the route that Washington’s forces took 240 years ago following the 2nd Battle of Trenton. This event would not have been the same without their amazing contributions. Bravo men! Huzzah!All in all, this truly was an amazing event. We had wonderful opportunities to really interact with the public. Some of our favorite moments actually came from those who didn't realize the event was happening. In order to warm up, there were several times in between "vignettes" that members would duck into a coffee shop. While we often received strange looks, there were many who approached us to ask what was going on. This offered many opportunities to really talk with people and explain some of their history. This event was unprecedented in reenacting in many ways. We interpreted situations that the public doesn't normally think about or interact with. It gave us a chance to bring to life an aspect of military history that in fact has very little to do with battles. And of course, the battle itself was spectacular. Thank you so much to everyone who came together to plan this event, participate, and attend it. It could not have happened without all of you. We look forward to many more "funcomfortable" and successful events this year!God Save the King!Katherine Becnel

Photo by Richard Patterson, the Old Barracks Museum, TrentonThis amazing group of guys survived sub-freezing temperatures and 5 inches of snow to march 14 miles in the middle of the night from Trenton to Princeton. They followed the route that Washington’s forces took 240 years ago following the 2nd Battle of Trenton. This event would not have been the same without their amazing contributions. Bravo men! Huzzah!All in all, this truly was an amazing event. We had wonderful opportunities to really interact with the public. Some of our favorite moments actually came from those who didn't realize the event was happening. In order to warm up, there were several times in between "vignettes" that members would duck into a coffee shop. While we often received strange looks, there were many who approached us to ask what was going on. This offered many opportunities to really talk with people and explain some of their history. This event was unprecedented in reenacting in many ways. We interpreted situations that the public doesn't normally think about or interact with. It gave us a chance to bring to life an aspect of military history that in fact has very little to do with battles. And of course, the battle itself was spectacular. Thank you so much to everyone who came together to plan this event, participate, and attend it. It could not have happened without all of you. We look forward to many more "funcomfortable" and successful events this year!God Save the King!Katherine Becnel