Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

Arms and Equipment: Cleaning the Firelock, part 2.

This installment of Arms and Equipment will be focused on surface treatments forIron, Steel and Brass.

Two Reproduction Bayonets likely made in the same factory overseas. Typically, many reproduction arms are mirror polished, inconsistent with known artifacts, and tools used by soldiers of the American Revolution. Cleaning arms correctly can be a very cheap way to begin “de-farbing” your firelock.

In 1786, Oxford Militia Serjeant Major Henry Trenchard published a pamphlet entitled “The Private Soldier and Militia Man’s Friend”. The Volume is an interesting look into the ordinary, day-to-day maintenance necessary for service in the militia or the regular Army. Just over 30 pages, Trenchard devotes half of the work to maintaining cleanliness of arms, accouterments and uniforms and contains valuable recipes and techniques used by the ordinary enlisted soldier:

“First you must provide yourself with a hand-vice, screwdrivers, rubbing sticks, and leather free from grease, oil, emery, crocus martis, &c. The rubbing sticks for the arms should be made of deal wood of different sizes,, with leather glued on in the following manner: Make the rubbing sticks very smooth, and on one side of it lay down the hot glue, and on this lay your leather and press it down; then lay some glue on the leather, and on that lay some emery, and press it a little into the glue, them be well dried; with this use oil and emery, brick dust &c; if you apply them properly by rubbing the arms well, they will give your arms a smooth surface you are next to proceed to polish them; take crocus martis, and clean dry leather, rub the part which you want to polish until it is warm, when it will acquire a very fine darkgloss”

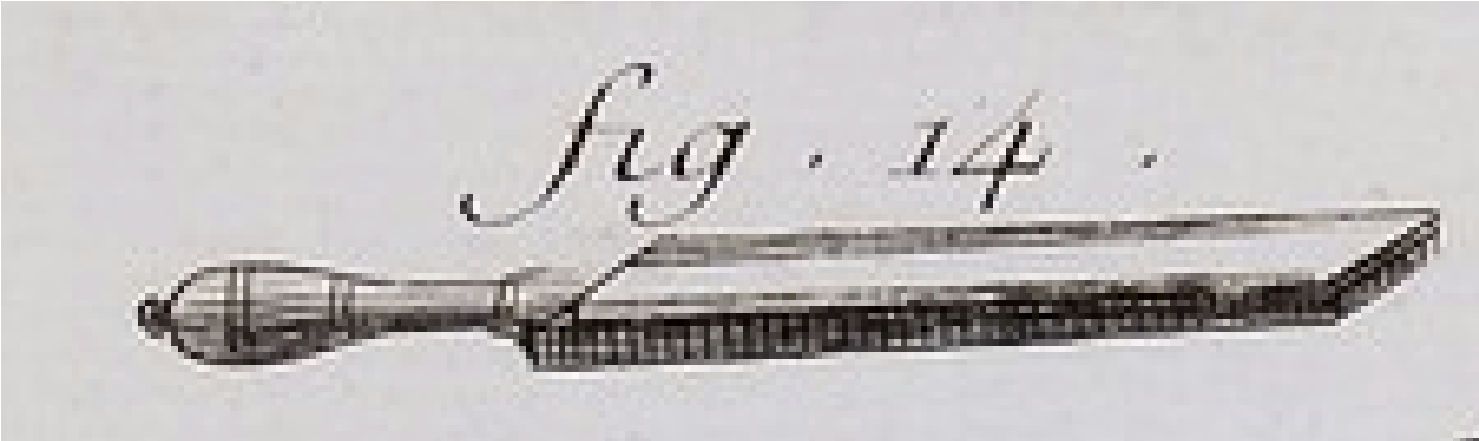

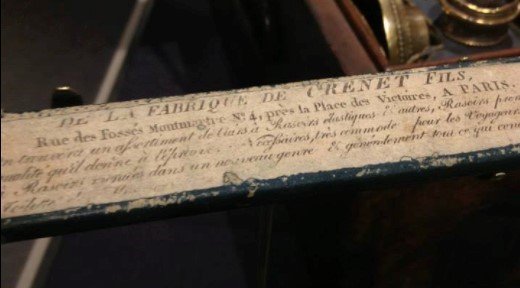

Trenchard’s above description of the rubbing sticks, serve as polishing strops, used in sharpening and polishing metal. A hint of what these may have looked like is from the Diderot’s Encylclopédie depicting tools from the cutler or Coutelier. One of those tools, described as a cuir à repasser, which was a “leather board” for polishing.

Another example of such a tool is in the French manufactured traveling case of Frederic Franck de la Roche, who served as an aide-de-camp to Marquis de Lafayette, in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society. From the original pasteboard case, it is clear that the strop was to be used with polishing razors for shaving.

A few years ago I made this little strop, with a piece of scrap wood. Contact cement is a good adhesive if you’ve never used hide glue before. I used a piece of buff leather. I made it small to easily fit in any type of cartridge pouch, or pocket.

Such polishing boards/strops can be extremely useful in getting metal mirror bright. However, such a finish is unnecessary to strive for during ordinary cleaning “in the field.” All that is needed is oil, leather scraps, linen scraps or tow, and brick dust.

First, take two small pieces of brick and rub them together, collecting the dust in a small container. Take your Leather and/or strop and apply a little oil. Apply brick dust into leather by dipping or sprinkling; rub in a circular motion throughout the entire surface you wish to polish.

The Strop is very useful for flat surfaces, and areas of heavier rust. The leather scrap is very useful in curved and hard to reach areas. Experiment with your own techniques. For bigger polishing jobs a “paste” made from oil and brick dust can be very convenient. The more you polish the better it looks!

Sword before polishing:

Typical light rust from carrying in the field.

Sword after polishing:

Once complete, wipe down with a piece of tow, or scrap linen, cleaning out tight spots of brick dust.

Repeat as necessary. A final polishing option is to use rotten stone (a Google search revealed many places to purchase) in a similar manner on a separate clean piece of leather for a final polish, or as Serjeant Major Trenchard put it “a very fine gloss”.

After handling, a quick wipe-down with a lightly oiled rag will help keep rust fromdeveloping.

Thanks to Google Books, Trenchard’s book is available for free online:Google Books

ANDREW KIRKhas been involved with American Revolutionary War living history since the age of 13. Taking an interest in material culture of the British Army has led to creating reproductions of artifacts for TV, Film and Museum Projects. Trained as a fine artist and educator at Maryland Institute College of Art and has been a secondary art teacher in Maryland for 7 years.

The Things We Carry: On the Strength of the Army

A couple weeks ago we had a member of the 17th Regiment of Infantry, Damian Niescior, write about all the things he carried during a weekend in the 18th century as a soldier in the British Army... this week we have a follow up post brought to you by Carrie Fellows, who has been working and recreating 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years. A year or so ago Carrie did a symposium with Kimberly Boice's: Historie Academie, which I happened to attend where she did a talk and workshop on how to pack for an event. So upon request it reminded me that she'd be the perfect fit to talk about what a follower of the army would bring with them.

Read Damian's blog post here.

- Mary S. an attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry

It can be difficult to explain to people what I do for fun. I combine my passion for history and the outdoors by interpreting the lives of women who, out of necessity, followed the Continental Army (and occasionally, the British army) during the American War for Independence. I have portrayed a laundress, an officer’s servant, a refugee, and a soldier’s wife, but regardless of whom I portray, the things I carry with me may vary slightly according to season, but remain essentially the same. Over the years, I have refined and limited the number of objects I carry, lightening my load for travel on foot over long distances, rough terrain, and the occasional river ford.

Records of what women carried are practically nonexistent, but one can find clues in runaway ads, military records, and the occasional primary source. Women attached to the army had only what they brought away with them, or acquired on the road. Women “on the strength” of the army were entitled to a half-ration of food (children received a one-quarter ration.) I am always hungry, and as rations aren’t always available, carry enough food to get by.

Tied about my middle, under my gown, a pair of pockets (1) is suspended. These contain both modern items (pocket on right) and period ones (pocket on left). I often leave my phone in the car unless I need to take photos for a talk or article, or will be in the deep backcountry.* My car keys (40) are pinned firmly to the inside bottom corner of my left pocket. In my right pocket: a sewing kit (2) or “housewife” – a roll of cloth with pockets to hold sewing supplies and tiny items like sleeve buttons, also a linen handkerchief (3), pocket knife (4), linen or woolen mitts (5), period scrip and real cash in a reproduction pocketbook (6), lip balm in a tin container (7).

I carry most of my gear in a wallet (8) – a rectangular cloth bag with a slit opening in the center. One places items in each end, then twists the entire thing at the center, closing the slit and forming a kind of narrow strap, then slung over the shoulder. I try to segregate the two ends into food/related items and clothing/personal items. The food side holds a small bag of cornmeal or rice (9), cheese wrapped in 2 layers of linen (10 - the inner one dampened with vinegar); a cured sausage wrapped in brown paper (11), a small bag of walnuts (12), bread (13), tea (14), salt (15), seasonal vegetables (16), a spice bag, grater, candle ends and extra corks (17), paper packets of flour and pepper (18), and sometimes I even remember my fire kit: flint, steel, charcloth and tow in a tin box (42). Food-related items include a turned wooden bowl (19), which can serve as both drinking and eating vessel, an eating spoon (20), and a linen towel (21).

In the other end, I carry extra clothing items tied up together in a large kerchief (22): moccasins (23) and a man’s wool cap (24) for sleeping in, stockings (25), neck handkerchief (26), and a small paper notebook (27). Some also carry a clean shift, but I do not, as I am rarely in a situation where there is privacy sufficient change it. Also: a tiny modern first aid kit in a red linen bag (28), personal toiletry items in another small drawstring bag: a tin box with soap and mirror (29), horn comb and bone toothbrush (30), handwoven wash towel (31), spectacles (32), allergy meds &, contact lens case (not pictured). Reenactor etiquette requires one to manage any non-historic personal care out of view as much as possible. Optional items, depending on the planned activity: a small bundle of mending patches and yarn (33), and a darning egg (34) to occupy time and to trade (mending skills have value), a large wooden cooking spoon (35), and a small axe (36). If there’s room, “luxury” items include a ceramic cup (37) and a big linen wallet that doubles as a straw tick (38).

I usually carry just one blanket (with a wool petticoat and cloak inside) rolled up, tied together at the ends to form a “U”, and carried across my body. I put on the wallet first, then the canteen (39) - the wallet cushions the strap - then the rolled blanket over that. The blanket helps keep both wallet and canteen secure, close to my body, and quiet as I walk – or run.

The last thing I pick up is my small iron pot (41), with its sheet iron lid tied on so it doesn’t rattle or become lost. If I have eggs or fruit, I pack it in the pot. It goes to every event with me. I hadn’t thought about it before, but that little pot – representing security, hot food, comfort (and home?) connects me to the women I portray who carried what they most valued when they followed the army.

*Nothing ruins an accurate setting faster than when the smartphones come out and glow blue at night.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

A Layman’s Guide to Historic Research

This week after a few weeks of rather heavy research and unit development blogs, writer Kyle Timmons joins us again to welcome back the website with a light hearted research blog. If you've missed the blog, it is back! Thanks for standing by us.

Mary Sherlock - An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry.

Just a disclaimer to start off with: I AM NOT A HISTORIAN, HISTORY TEACHER, RESEARCHER, ARCHAEOLOGIST, OR ANYTHING LIKE IT. I am a simple person who enjoys history immensely and I’ve read and studied history much of my life. HOWEVER, I have the honor and privilege of being friend and acquaintance to many truly gifted and highly regarded Professional Historians. They’ve taught me so much about the 18th Century, the Revolution, and the British Army. But most importantly, they’ve given me the tools research on my own and to hunt down information that is of interest to me, and hopefully I can turn that information around and further benefit the hobby, the community, and our understanding of the 18th century. I’m going to take some time and share some of those tools with you.

- BE SUSPICIOUS. The moment that you read that previous statement is gone, and is never coming back. You can’t change it. But in an hour when you’re eating delicious food and playing on your phone you’ll likely forget about it. Maybe tomorrow you’ll share your memory of this blog with a friend, but you’ll share the points in your own words. You might get things wrong. 60 years from now when you’re telling your grandchildren how you first got into reenacting you’re memory of the antiquated computer or smart phone you used back then will be colored by nostalgia of the past.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

- YOU MAY BE WRONG BUT YOU MAY BE RIGHT. The modern age we live in is actually an exciting time for someone with a history interest. That’s because high definition imagery and the internet are making it easy for someone in the United States to view an artifact or painting housed in England, or Germany, or anywhere else in the world in detail from the comfort of their home. Books, journals, etc. that are no longer in print or are one of a kind have likewise been digitized and can be accessed around the world either as open domain files or through special archives. This means information that has either laid unseen in a private collector’s library, or has only been accessible to a select few can now be accessed by the entire world. This tidal wave of new information is changing how we see the 18th century in numerous ways. A good example of this is the silk bonnet. Earlier it was commonly believed by reenactors that a silk bonnet was something that would have been out of reach to the “lower sort” of women in the 18th Now however, after searching through runaway ads here in America, looking at artwork from England, it’s clear that these beautiful articles of clothing were available to a much wider range of women than was originally supposed. Our knowledge of the 18th century is largely a collection of theories; strong theories mind you, and ones back up with multiple bits of data to support them. But as the data changes, our conclusions must change as well.

- IMAGINATION IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR KNOWLEDGE. Even without photographs, film, or with the amount of material culture items industrial-age historians are accustomed to there is a very large amount of source material and artifacts from the 18th There is no excuse for not making use of this material. When you choose an impression, be specific about what it is you’re trying to do. Are you doing a civilian or military? What nationality? What year and where are they? What is their social class? All of this is important. Military clothing, though it follows the fashions of the time, is distinct in many ways from its civilian counterparts. You won’t find examples of civilians in 1777 Philadelphia wearing gaitered trousers. The nation is important because every nation has their own idiosyncrasies. Time and place also play a factor. Fashions, like today, change with time.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Social class is also of major importance. Some clothing item are compatible to some extent across the classes. For instance, men’s shirts of the day are universally of a good quality in terms of stitch work (though they are often made of different grades of material). In other ways they’re very different. A laborer isn’t likely to be wearing a silk coat and breeches. Likewise, a gentleman isn’t likely to have an osnabrig (a kind of course natural linen) shirt and the same clothing items as a private soldier in the army (any army). Doing any impression costs money. To do a higher class impression well costs more money, just like how it’s easier to get a suit from Boscov’s (like me!) than to have one tailored to your desires in London or L.A.

- QUALITY IS A QUANTITY ALL ITS OWN. This is the last point I want to make. I’m immensely proud of my impressions, of which I have two…and a half. I have a 17th Regiment soldier’s kit, a kit for the Philadelphia Associators, and a mostly finished civilian impression. I say “mostly finished” because my coat is sitting sleeveless and partially un-lined on a chair. The reason I’m immensely proud of my kit is that I’ve made much of the clothing items I possess. My 17th Regimental and its waistcoat were the first 2 sewing projects I’d ever done. The things that I didn’t make were made by friends of mine who are very skilled at their trades. That’s what makes a good 18th century impression. Clothing of the time was done by hand, not machine, and most men’s clothing is fitted. You can see this in the paintings and sketches of the time. Clothing was expensive for these people, and they took care of what they had. They also dressed as well as they could. You should, too. If you’re new to this period, or reenacting in general, my advice for you is this. If you’re thinking of buy “off the rack” clothing, don’t. Save your money. Reenacting isn’t going anywhere. There are people out there who will take your measurements and whip you up a set of period clothing. Many of them are really good, and naturally they charge for that service. It might take you time to get that money together but the quality will be worth it and you won’t have to go and buy a better piece of clothing down the road.

If you have an aptitude for sewing however, or you can get with a group of people who know how to sew and can teach you, then you’re life probably just got a lot easier. With the right patterns for your clothing, patience, and help, you can make your own clothing for a much more agreeable sum of money. On top of that, you learn a valuable skill. And once you can sew, you can make yourself into anyone!

The study of history and the recreation of it is a noble hobby. But to do it right takes work, research, money and commitment. But most importantly, it takes networking with good people. That’s how I have learned so much, and really it’s the people we hang out and work with that make this hobby so great.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.