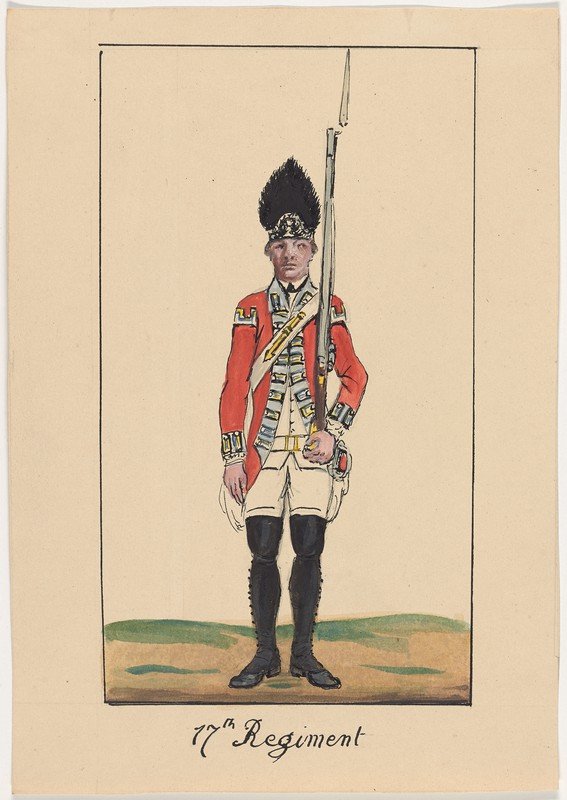

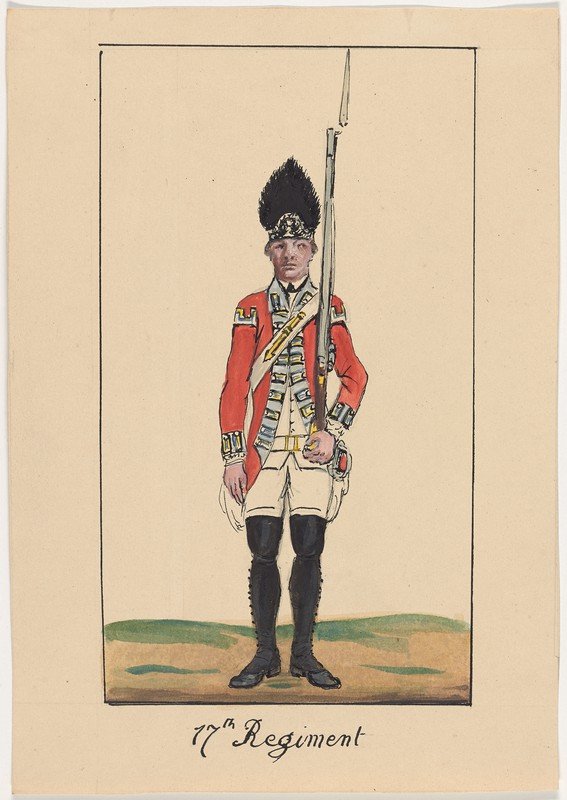

In this second installment of the series, Mark Odintz, Ph.D., returns with a look at the officers who served in the 17th's Grenadier Company during the war. As always, we are grateful to Mark both for choosing the 17th Regiment for his studies and for sharing the fruits of his labor with our readers. If you enjoy these and Mark's other entries, please post in the comments: we're encouraging him to transform his dissertation into a book!

- Will Tatum

In this post I will provide sketches of the three officers who served in the grenadier company of the 17th during most of the American Revolution, with the addition of two others who joined it in 1781. For most of the period of the war the regiment contained twelve companies: eight companies of the line; two specialist companies, grenadiers and light infantry, known as the “flank” companies; and two “additional” companies that remained in the British Isles recruiting and forwarding men overseas to the regiment. Flank companies were usually detached from the regiment during the war and served in separate battalions of grenadiers and light infantry. Their officer compliment consisted of a captain and two lieutenants, in contrast to the average line company, which contained a captain (or field officer or captain lieutenant), a lieutenant and an ensign. Enlisted grenadiers were chosen in part for their height and physique, though this probably became less important on wartime service, when qualities of steadiness, toughness and endurance were paramount. For officers, service in the flank companies was prized as a vehicle for furthering one’s reputation, career and professional expertise. Eleven officers served in the light company of the 17th during the war, reflecting its almost constant active service and high level of casualties. The grenadier company, in contrast, though it saw hard service in the field, was officered almost entirely by three men, William Brereton, Gideon Shairp (or Sharp) and Lawford Miles, with two others, Alexander Saunderson and James Forrest, serving for the final two years of the war. Of the five three were Irish, one Scots, and one American, thus highlighting the national diversity of the officer corps during the American War.

William Brereton, captain of the grenadier company of the 17th for much of the Revolution, is a classic example of the commitment of the Protestant Ascendancy of Ireland to military service. He came from a family of Anglo-Irish gentry that had come over to Ireland from Cheshire in the 16th century. His grandfather, William Brereton of Carrigslaney, County Carlow and Lohart Castle, county Cork, had served as High Sherriff of County Carlow in 1737. Our William’s father, Percival, was the third son, and died a captain in the 48th Foot with Braddock in 1755. Four of William’s uncles also served in the army, and his mother, Mary Lee, was the daughter of a general. A letter from William’s uncle Edward to Lord Amherst, soliciting a company for himself during the American Revolution, demonstrates the family ties to the military and how the connection had carried over into the next generation. He laid out his service and went on to state he “had 4 brothers officers, one of whom was killed with Braddock, and now 3 nephews in the Service.” (Burkes Family Records, Brereton Family; WO34:154, f. 147 Edward Brereton to Amherst).

William was born in 1752 and purchased an ensigncy in the 17th on August 2, 1769. When Captain Edward Hope died in 1771, the succession went without purchase and Brereton became a lieutenant on Nov. 14, 1771. He became adjutant by purchase of the 17th in February, 1775 and continued to serve as adjutant until April of 1777. He purchased the captain lieutenantcy of the 17th on May 24, 1775 and purchased his captaincy later that year. He was commanding the grenadier company of the 17th by July of 1776 and, with the exception of a brief interval in July of 1780, continued to lead the grenadiers until he was promoted out of the regiment in April of 1781. (Record of service in WO25:751, f.217; dates of service in grenadier company from the rolls in WO12).

He was clearly an outstanding combat soldier, and distinguished himself during his six years as commander of the grenadier company. In 1779 his former commander, Earl Cornwallis, recommended him for promotion by summing up his service in the 17th- “He did his duty with the greatest spirit & zeal during the three campaigns in which I commanded the Grenadiers, but he more than once stepp’d forth when not particularly called upon, and without the too common apprehension of taking responsibility upon himself by his courage and good sense render’d essential service…” (WO1:1056, f. 317). One of his bolder exploits involved the capture of an American frigate, the Delaware, during the Philadelphia Campaign. On September 27, 1777, the thirty-four gun ship was attempting to deny the Delaware River to British shipping when it ran aground. A mixed force of British marines, sailors and Brereton’s grenadiers captured the ship, refloated it, and incorporated it into the Royal Navy. (Webb, Services of the 17th Regiment, pp. 73-73; Taafe, The Philadelphia Campaign, pp. 112-113).

Perhaps the high point of his service as a grenadier came a few weeks later on the morning of October 11, 1777. An outpost on an island near Philadelphia under the command of Major Vatass of the 10th was surprised by a rebel force. Acting quickly and without orders, Brereton and Captain Wills, a grenadier officer of the 23d, put together a scratch force of grenadiers and Hessians, crossed over to the island, recaptured the post and rescued the garrison as it was being brought off by the rebels (WO71:84, Court-martial of John Vatass, 16 Oct 1777; and Court-martial of Richard Blackmore 21 October 1777). Continuing at the head of the grenadier company, Brereton was wounded at the battle of Monmouth in 1778.

After twelve years in the 17th Brereton purchased his majority in the 64th Foot in April of 1781. Late in the war Brereton commanded at one of the last successful British skirmishes of the war at the Battle of the Combahee River, outside Beaufort, South Carolina. On August 27, 1782, he was leading a foraging detachment (including a company from the 17th) from the garrison at Charleston when they were intercepted by an American force under Mordechai Gist and John Laurens (now of Hamilton the musical fame). Brereton ambushed the rebels, killing Laurens, capturing a howitzer and, after further skirmishes, returned to Charleston. He became a lieutenant colonel by purchase in the 58th Foot in 1789, and retired in 1792. Like many other retired officers he made himself useful during the lengthy crisis of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars by holding a number of other military appointments; serving as paymaster for a recruiting district, as an officer in the Wiltshire Militia, and as inspecting field officer of yeomanry for the Western District.

In 1784 William Brereton married Mary Lill, daughter of Godfrey Lill, Judge of Common Pleas for Ireland. Of his three sons who survived into adulthood, one entered the army and two served in the Royal Navy, continuing the tradition of military service. He lived at Chichester in England during his final years and died in November of 1830.

Gideon Shairp served as lieutenant of the company for the entire war. He came from a family of lowland Scottish landed gentry, the Shairps of Houston, co. Linlithgow (modern West Lothian). Born in 1756, he was the second son of Thomas Shairp, of Houston, whose children followed the classic pattern of gentry with strong ties to the services. Thomas, the eldest, inherited the estate, married and produced heirs; our Gideon entered the army, the third son went into the Royal Navy and the two youngest went into the army as well (family info from Burkes Landed Gentry, 1853, p. 1222 Shairp of Houston). Gideon purchased an ensigncy in the 17th on August 31, 1774, and was assigned to the grenadier company in August or September of 1775. As part of the augmentation of the army he was promoted to lieutenant without purchase on August 23, 1775 and served as the senior lieutenant of the grenadier company from 1775 through 1783. He purchased his captain lieutenantcy on Sept 14, 1787, became captain a month later and after twenty-one years in the 17th was promoted out as major to a new corps in May of 1795. He shifted to a more stable berth as major to the 22nd Foot in September of the same year and became lieutenant colonel to the 9th Foot in August of 1799. Gideon was serving as quartermaster general of Ireland at the time of his death in 1806. As far as I can tell, he never married. In his will he leaves his estate to his brother Walter, his baggage to his servant, and a ceremonial sword presented to him by the officers of the 9th to his friend, Major General Browning. (PCC Will proved 1806).

The third grenadier officer is another Irishman, Lawford Miles. His family was minor gentry in County Tipperary. His father, Edward Miles, gent, of Ballyloughan, died in 1778, leaving six daughters and five sons. At some point our Lawford inherited the estate of his uncle in Rochestown, and the family also owned land at Clonmel and Clogheen, all in Tipperary (Irish Wills, p.349; online list of Tipperary freeholders 1775-6) He entered the 17th as an ensign without purchase on May 1, 1775, and became a lieutenant, also without purchase, on September 8, 1775. He was serving as the junior lieutenant of the grenadier company by July of 1776 and served in the company at least until February of 1781. Miles purchased his company in the 17th on April 29, 1781 and was serving with the main body of the regiment at the surrender of Yorktown. He was the only captain chosen to accompany the regiment into captivity, and found his time as a prisoner had its dangers as well. He “was also one of the capts for whom the Americans drew lotts when Capt Asgill of the Guards was the unfortunate person” (WO1:1024 f. 775, Lawford Miles to Young, 7 Aug. 1784). This refers to the Asgill affair of 1782. In retaliation for the hanging of a rebel captain by American loyalists, George Washington responded by having British POWs of the same rank draw lots for hanging. Charles Asgill was chosen, but in the end the American Congress set him free. (see Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington, Asgill Affair). Miles retired from the 17th and the army in November of 1789. He died without heirs in 1809. Family sources style him as Colonel Miles at the time of his death, but I have found no evidence of further service in the regular forces. (BLG 1862, Barton of Rochestown).

Two other officers, Alexander Saunderson and James Forrest, joined Gideon Shairp in 1781 and served until the end in 1783. Saunderson was yet another member of the Irish gentry. The Saundersons of Castle Saunderson, County Cavan, came over from Scotland in the early 17th century. Alexander’s father, Alexander senior, was head of the estate and served as High Sherriff of Cavan in 1758. Our Alexander was the second son (see BLG of Ireland 1904, Saunderson of Castle Saunderson). Unfortunately for him, his father, at least according to family lore, fit the stereotype of the wastrel Irish gentleman. He was a spendthrift and a gambler and spent much of his time racing horses at Curragh and elsewhere. Rumored to have been a member of the Hell Fire Club in the Wicklow Hills, he became a wanderer after Castle Saunderson was damaged by fire. (Henry Saunderson, “Saundersons of Castle Saunderson”, 1936). Our Alexander was born circa 1756. He entered the army as an ensign in the 37th Foot on September 30, 1775 and became a lieutenant in the same regiment on May 20, 1778. He came to the 17th as a captain on April 29, 1781, and was Captain of the grenadier company by July of 1781. In 1783 the regiment was reduced from twelve companies to ten as the British army returned to the peacetime establishment, and Saunderson, as one of the two junior captains, was put onto the half pay. With the coming of a new crisis in 1792 he found his way onto active service by trading his half pay for a captaincy in the 69th Foot on June 30th. Saunderson remained in the 69th for the remainder of his career, becoming a brevet major on March 1, 1794, a major on July 1, 1796, and a lieutenant colonel on March 30, 1797. He left the service in 1800, and died childless in 1803, leaving his estate to his wife Aurelia. (PCC Will proved 1803)

Finally, we have an American, James Forrest, one of possibly eight or more in the 17th during the period of the revolution. He was born in 1761, the year that James senior, his father, moved the family from Ireland to Boston, so our James may have been born in Ireland. His father was a prosperous merchant before the war and lost his fortune as a result of his loyalist support of the British cause (E. Alfred Jones, “The Loyalists of Massachusetts”, 1930). James senior raised the Loyal Irish Volunteers in Boston in 1775, and contributed two sons to the British forces. Our James joined the 38th Foot as a volunteer in 1777. Gentlemen without the money to purchase or the influence to find their way into the service often joined serving regiments as “volunteers”, hoping to be appointed to vacant commissions after proving themselves in the field. James was wounded while serving with the 38th at the battle of Germantown and was appointed ensign in the regiment in October of 1777. A letter James wrote in March of 1780 seeking a company in a loyalist corps expresses the frustration of those trying to get ahead without financial means: “I have not the most distant prospect of promotion in the 38th, the repeated misfortunes my Father has met with since the commencement of the Rebellion put it out of his power to purchase for me.” (Clinton Papers, Forrest to William Crosbie, March 3, 1780). Instead of transferring to the loyalist units he was appointed lieutenant without purchase to the 17th Foot on February 19, 1781 and seems to have joined the grenadier company about the same time as Saunderson. James Forrest retired as a lieutenant in September of 1788.

Dr. Mark Odintz

conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

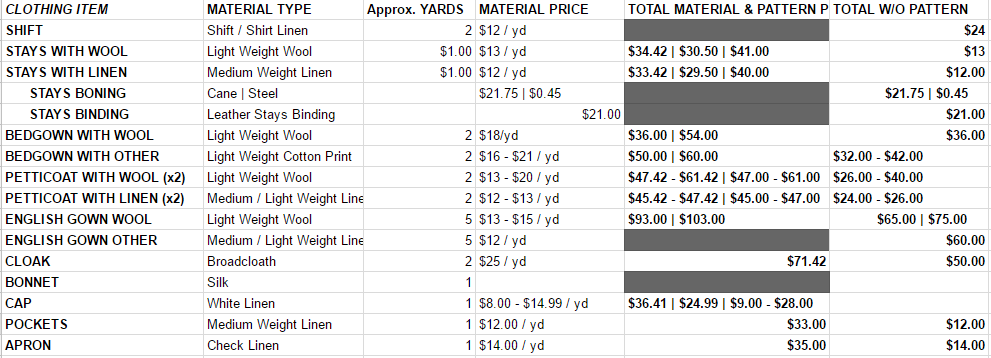

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

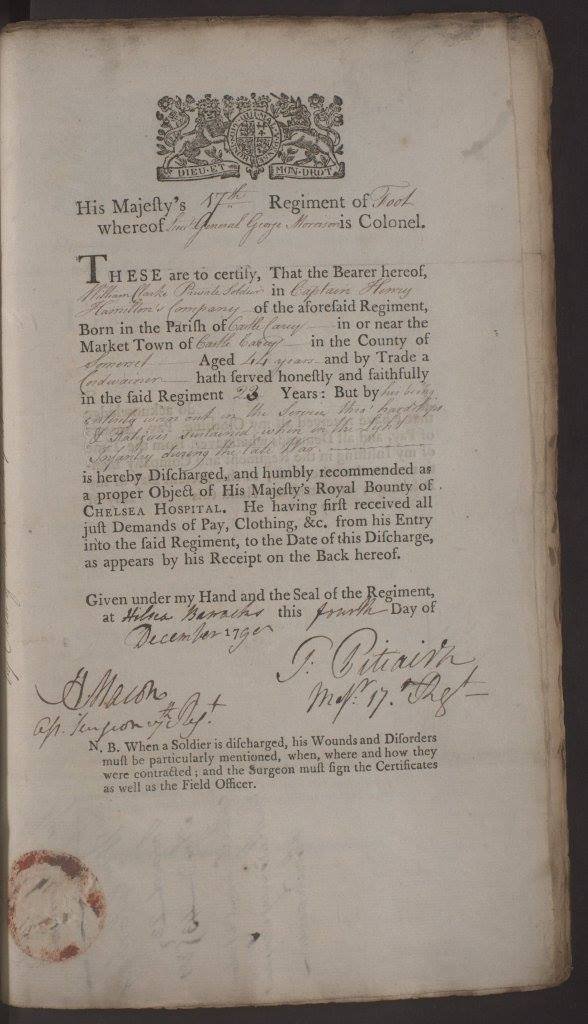

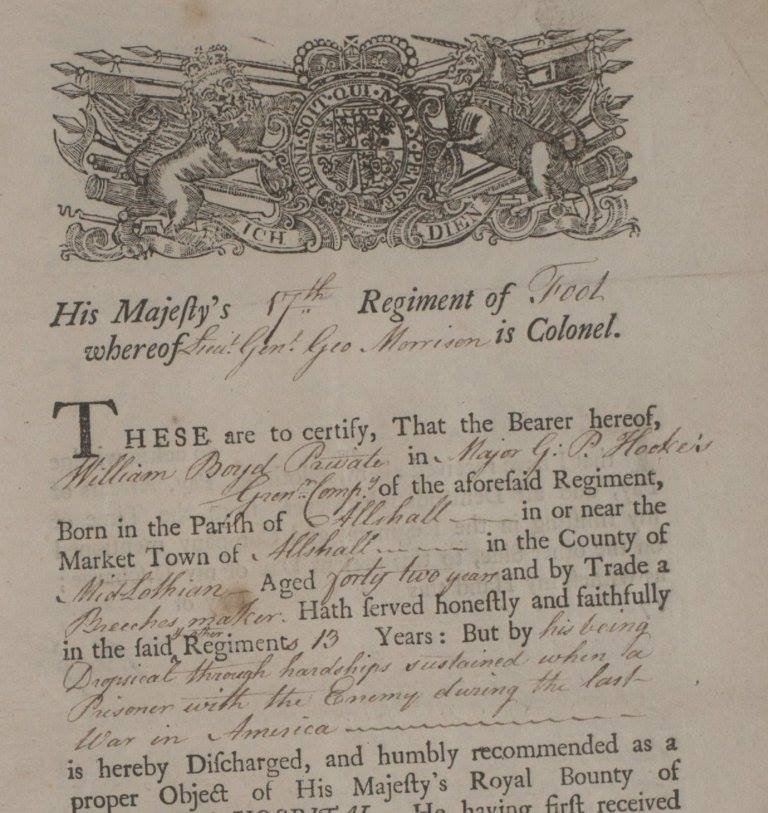

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books. Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

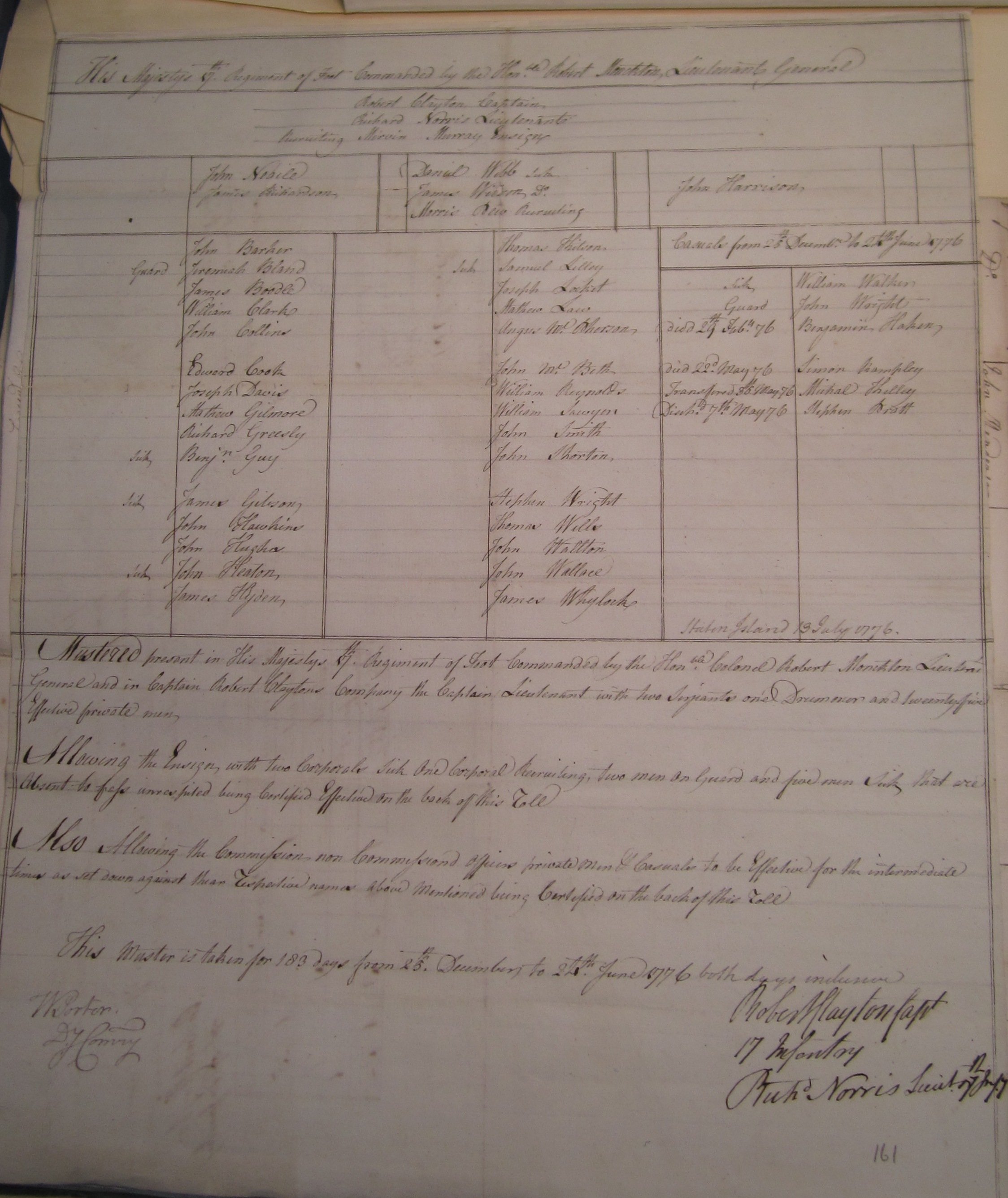

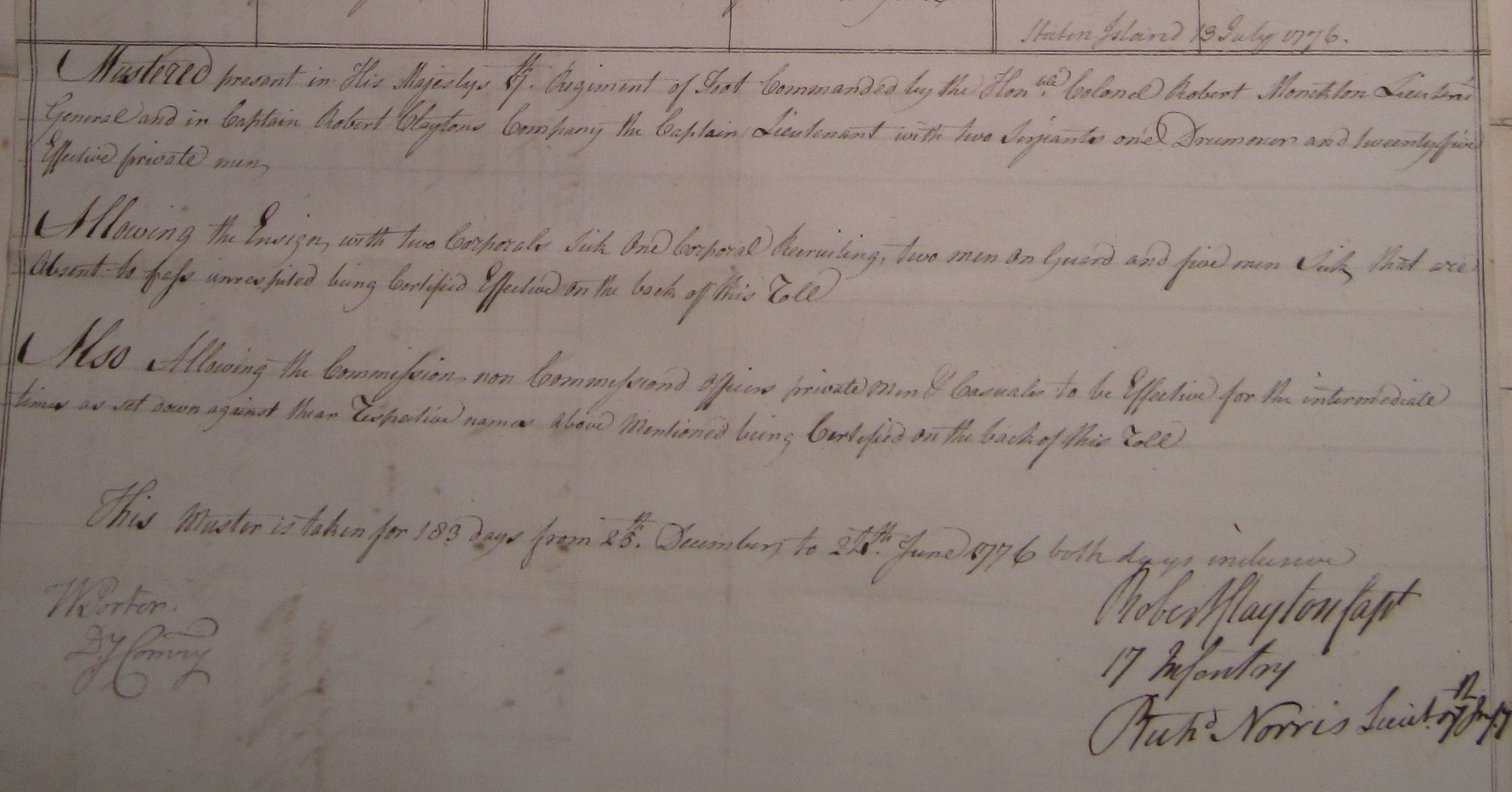

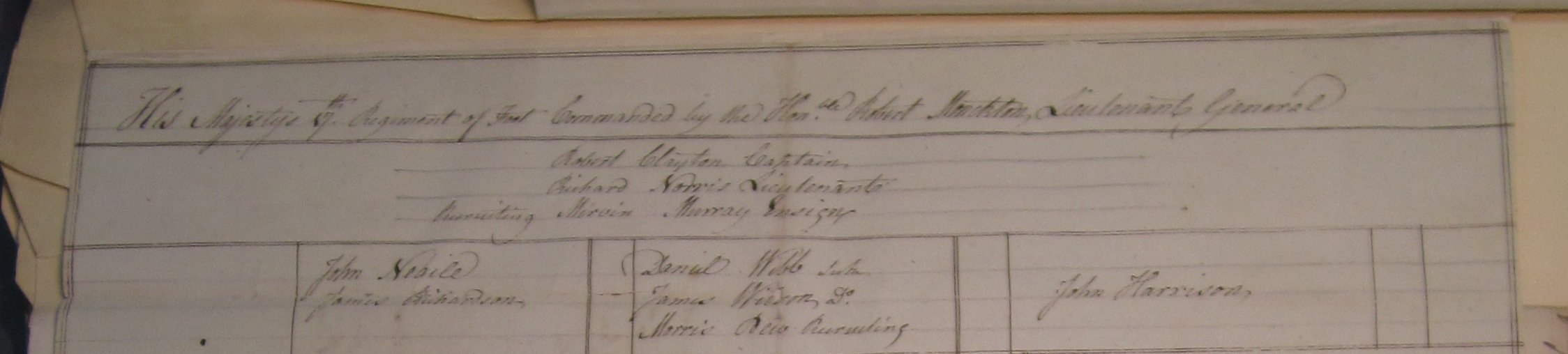

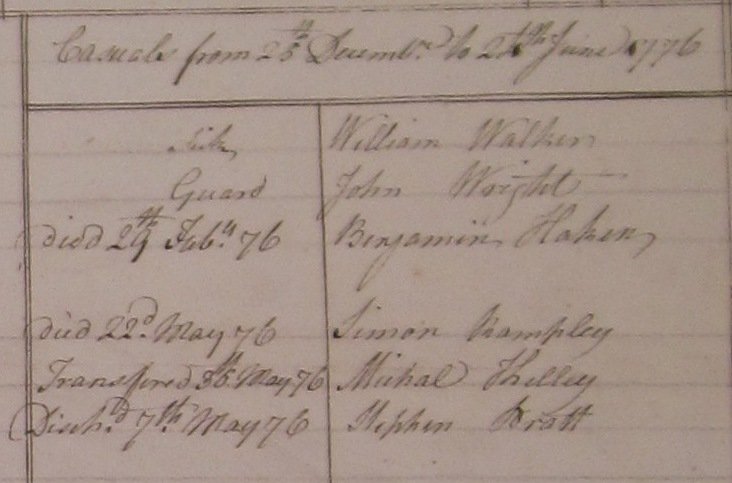

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

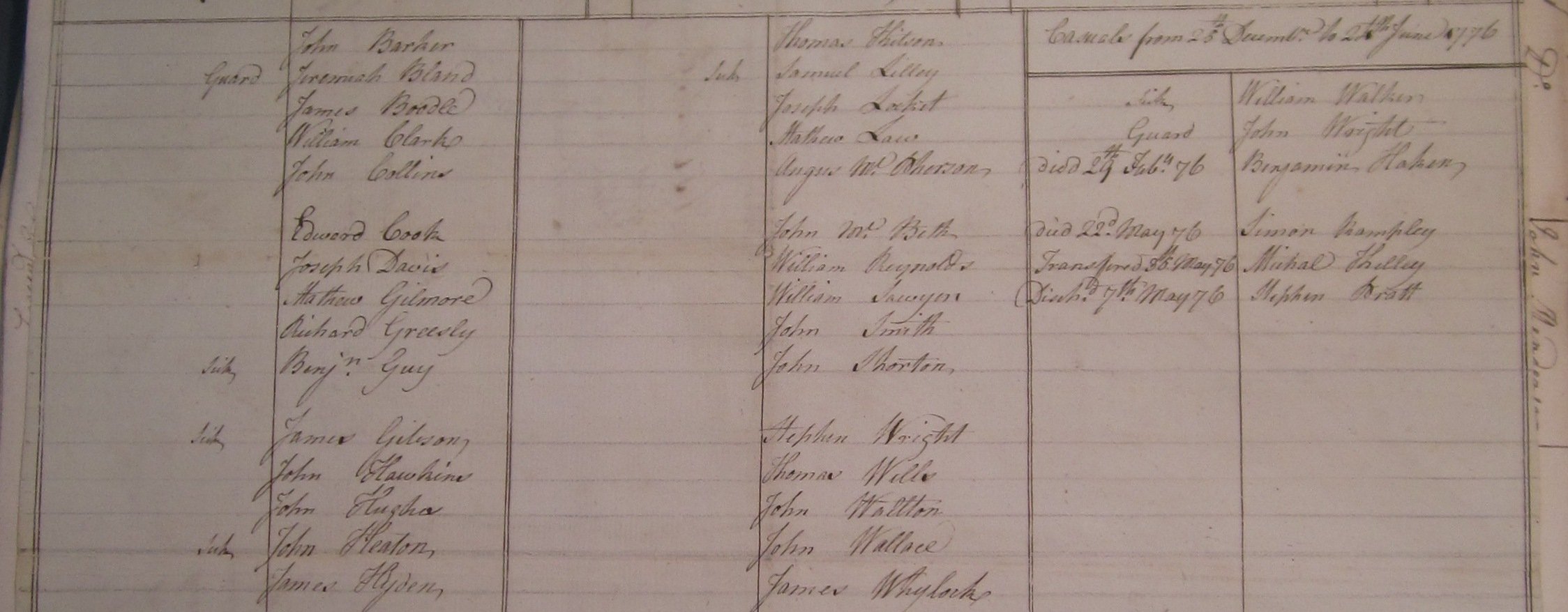

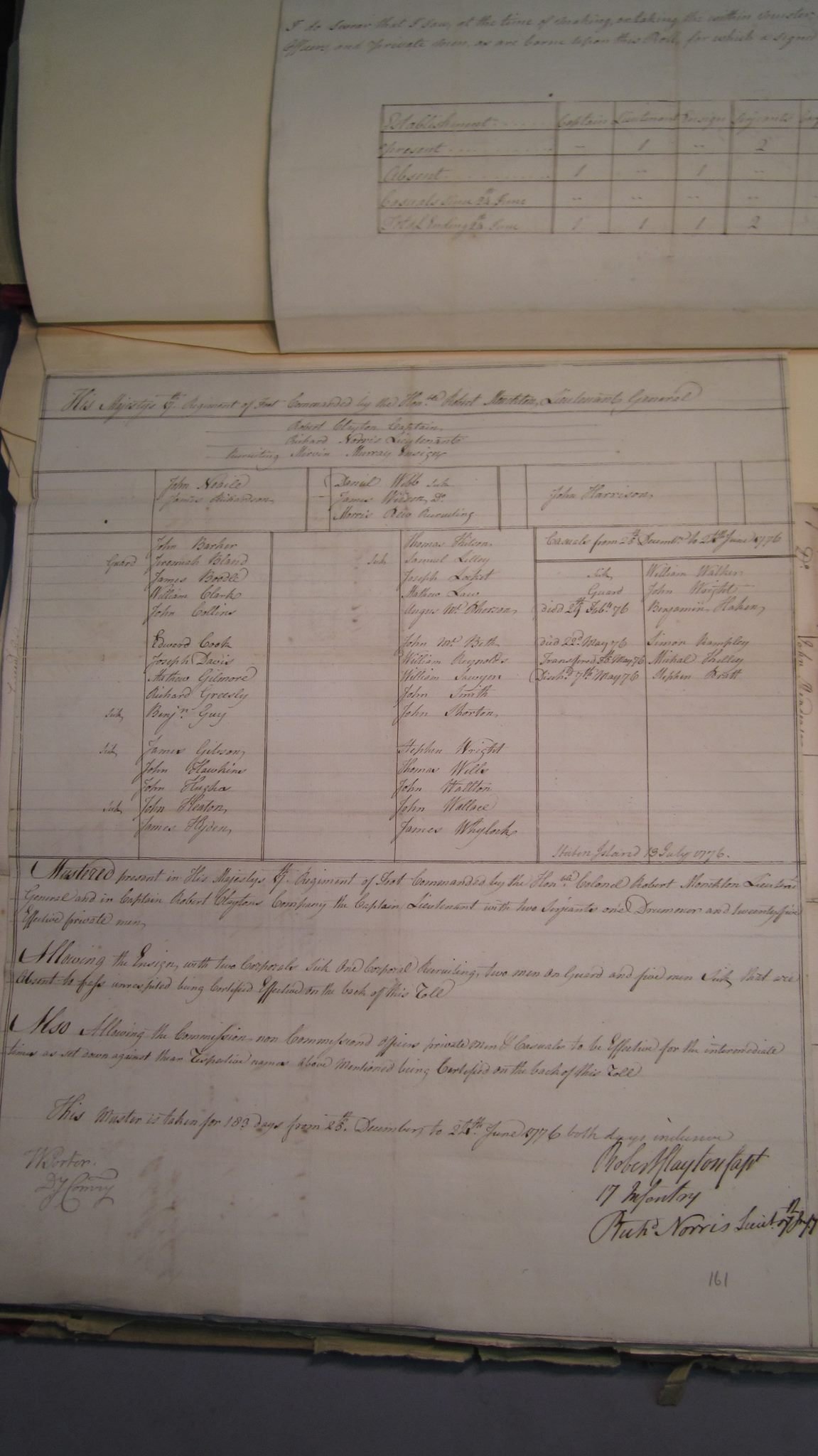

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

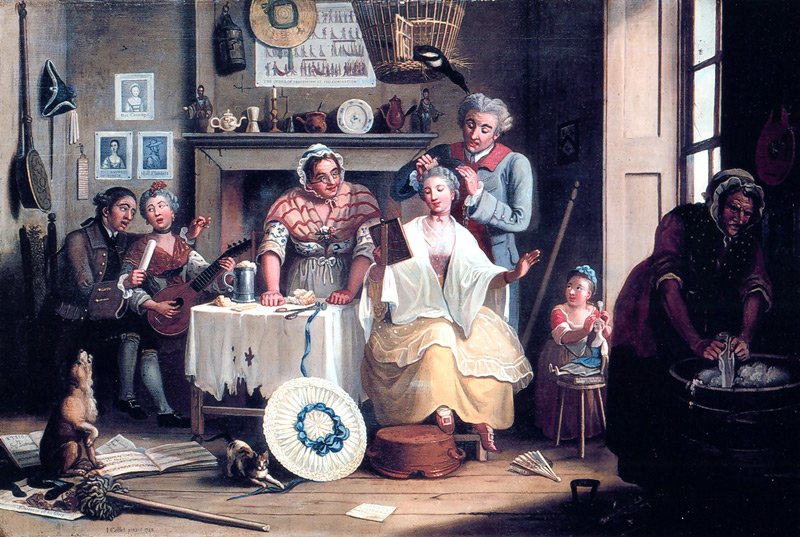

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations: violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo

Mary Sherlockis a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head follower' for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009.

Mary Sherlockis a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head follower' for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory. Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

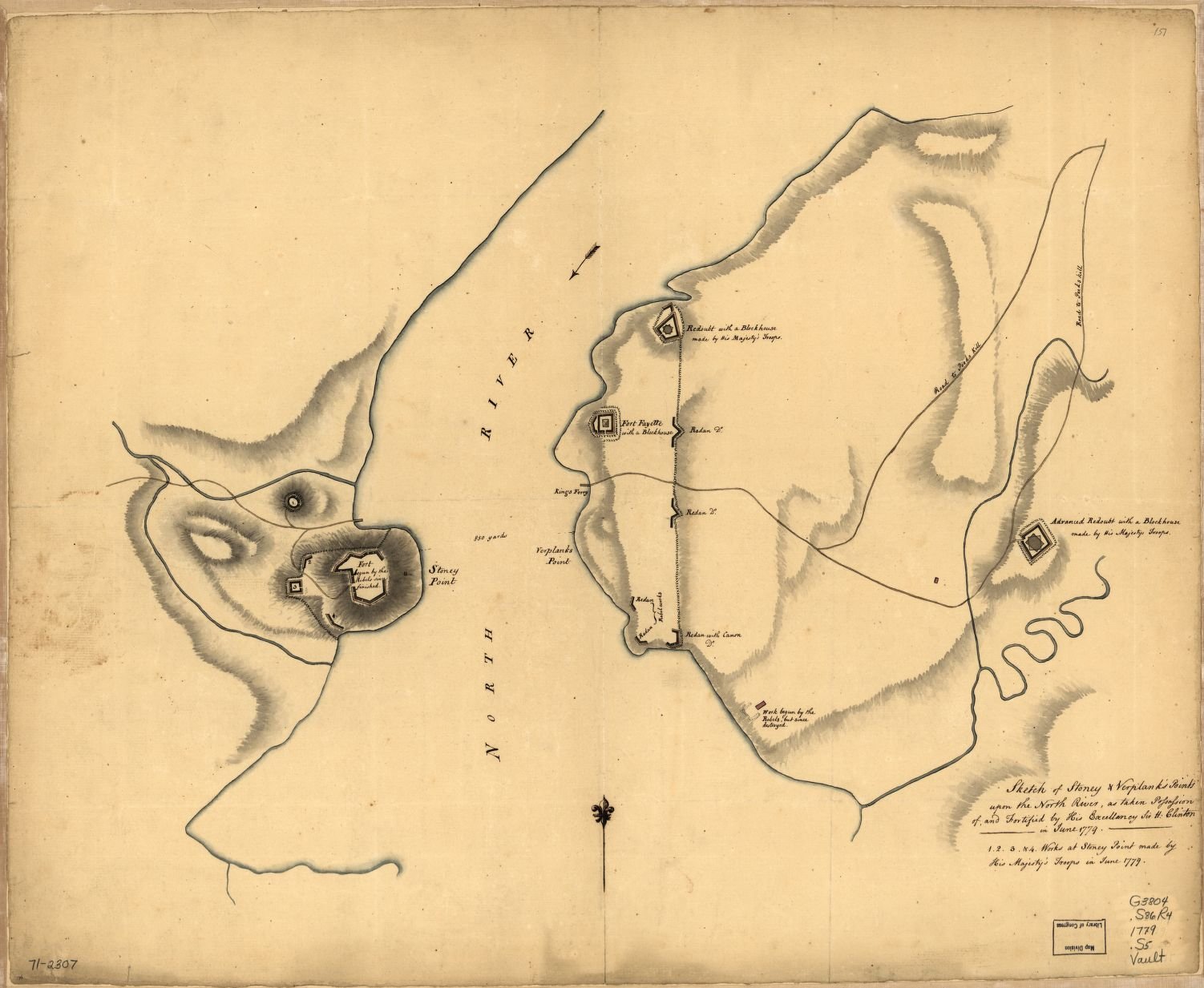

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of  Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Dr. Mark Odintz

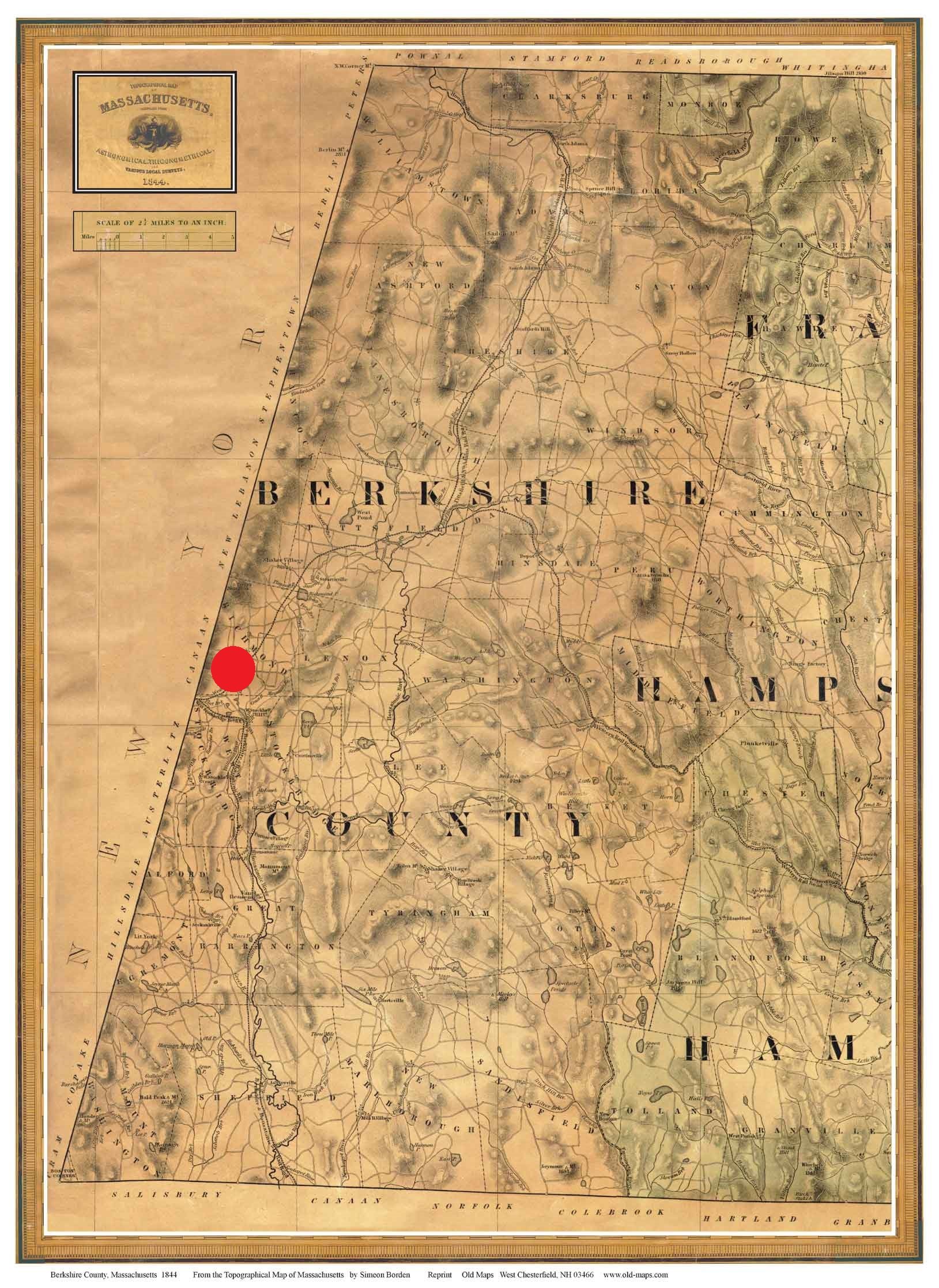

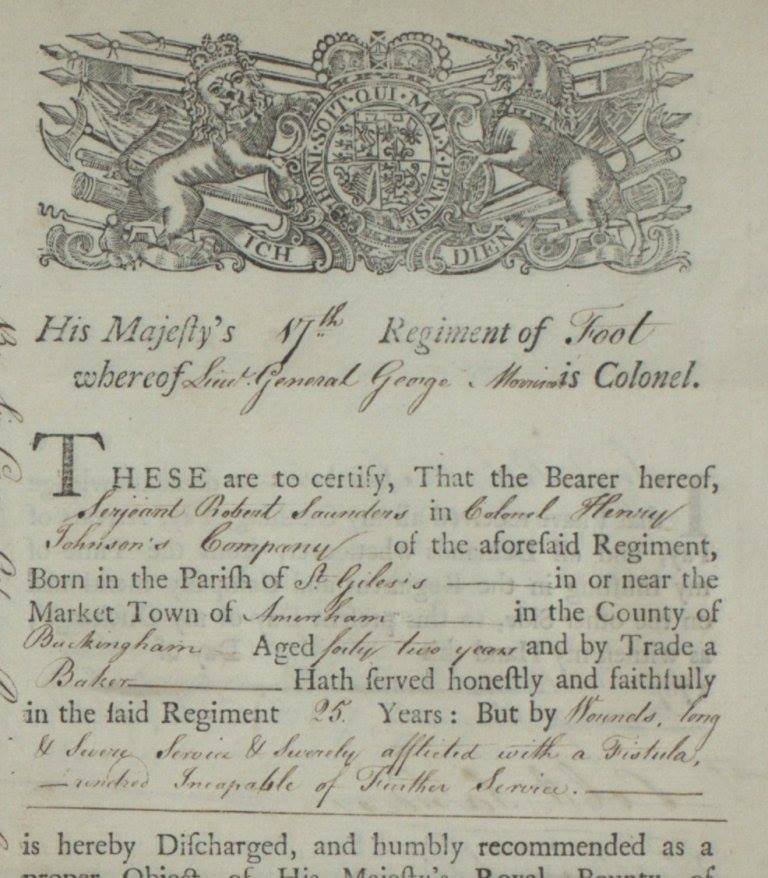

Dr. Mark Odintz Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

Photo by

Photo by