In today's installment, we feature legendary eighteenth-century British Army Historian Mark Odintz, PhD. Mark is the world's foremost authority on the trials, tribulations, and civilian origins of Revolutionary War-era British officers. His doctoral dissertation remains the definitive work in the field. We look forward to his occasional dispatches detailing the service histories of the 17th's officers and encourage him to prepare that dissertation for publication!-- Will Tatum

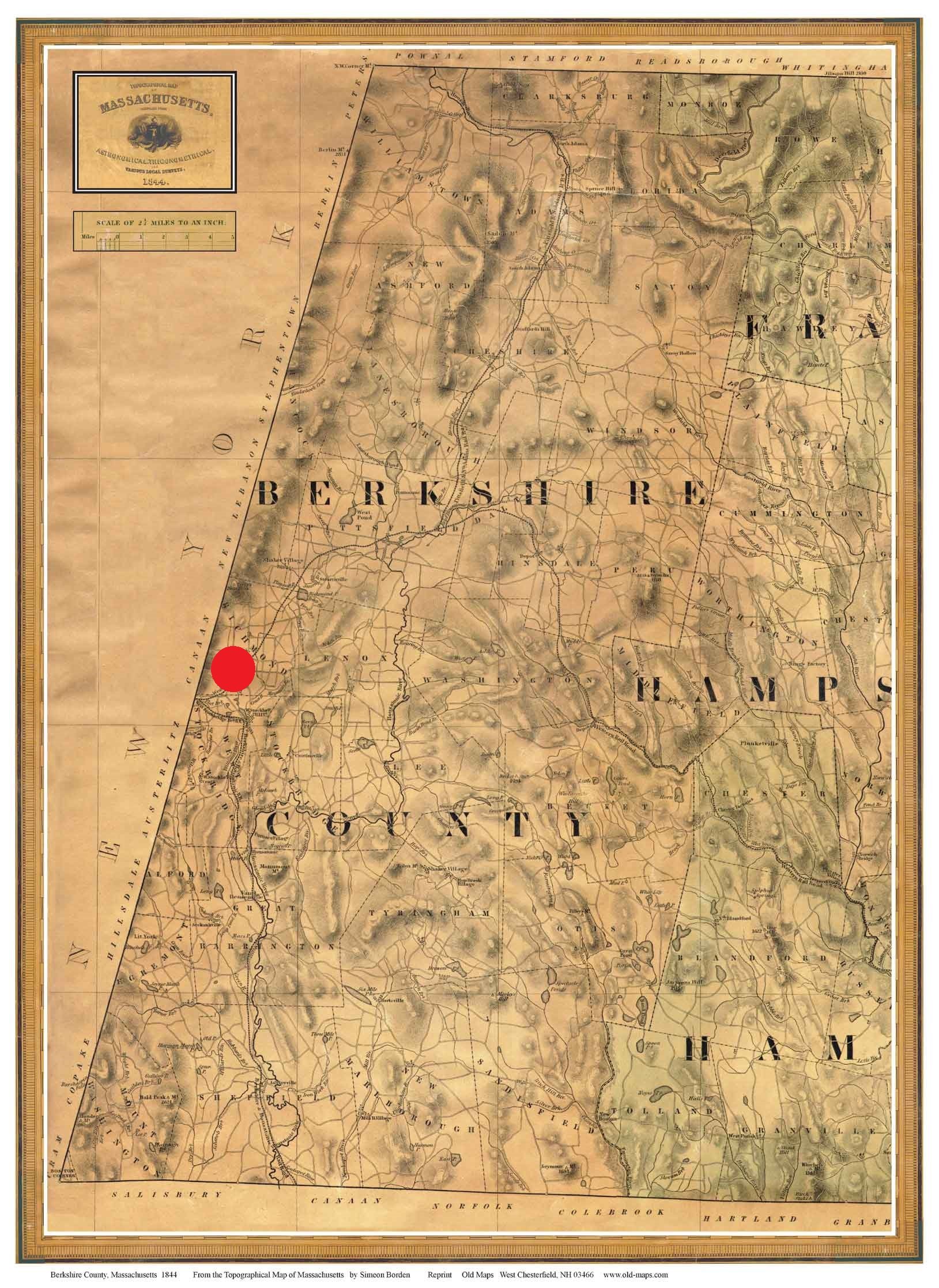

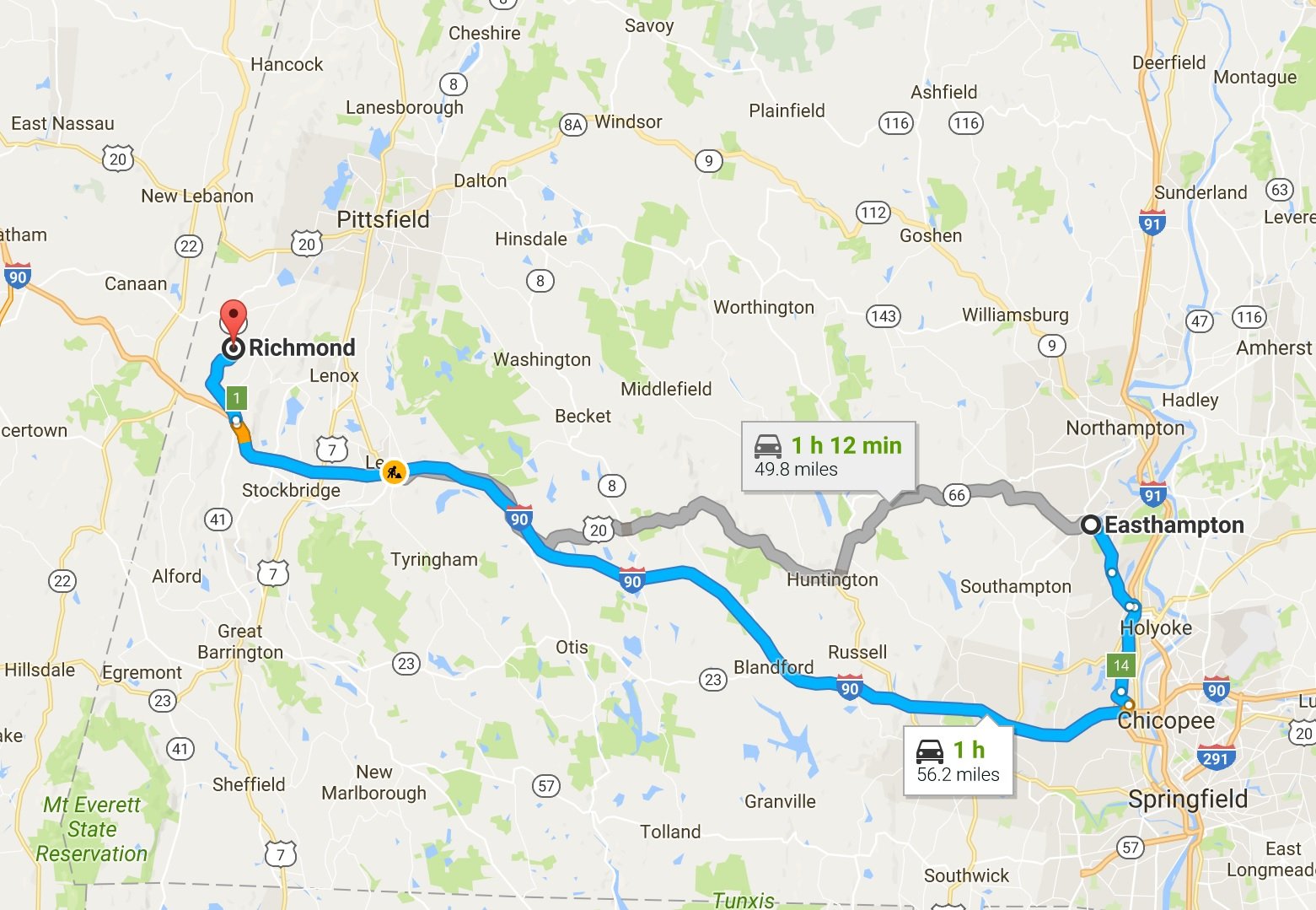

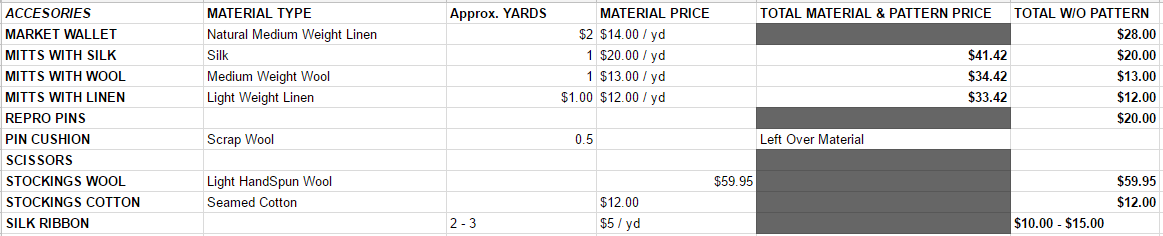

Way back in 1988 I completed a dissertation on the British Officer Corps in the mid-18th century. It is a collective biographical study of some 395 officers who served in four regiments of foot, the 8th, 12th, 17th and 35th, between 1767 and 1783. I used the sample to explore the social backgrounds, careers, attitudes and service experiences of British officers for a somewhat wider period, from the Seven Years War to the end of the American Revolution. The past few years I have been revisiting the project, seeking out further biographical details, revising, etc. with the hopes of producing a book down the road. What I would like to do for the blog of the 17th is to run an occasional series of biographical portraits of the company level officers of the regiment from the period of the American Revolution. It was an active regiment that saw more than its share of combat and non-battle attrition and as part of larger organization that was expanding rapidly it also saw a fair amount of regiment hopping among its officer personnel. Some ninety officers served in the 17th Regiment of Foot between 1775 and 1781. Twenty of these either left the regiment in 1775 or did not join until 1782-83. A further eight served in regiment very briefly, if at all, as they promptly transferred to another regiment. Six were field officers or colonels of the regiment. Twenty-three served in the regiment for three years or less during the war, leaving it through promotion, death or retirement. This left a core of thirty-three men who spent most of the American Revolution officering the 17th. This entry will focus on fairly typical member of the thirty-three, Robert Clayton.

Robert Clayton had the kind of career a fairly well-connected member of the gentry (not as elite as some, but better than most) could expect to have in the army of George III. He was a younger son of a younger son, but the family used their wealth, political influence and connections in several professions to ensure successful careers for their male offspring. The lottery of family demographics also played its usual part, leaving a childless Robert Clayton in possession of the estate as the last man standing at the time of his death in 1839.

By the early 18th century the Clayton family were landed gentry with several manors in Lancashire near Wigan and urban property in Liverpool, as well as considerable electoral interest in the borough of Wigan. Robert’s grandfather Thomas inherited the family estate and had five sons. The youngest, Robert’s father John, was described as a “gentleman, of Cross Hall, near Chorley, Lancashire” when young Robert entered Manchester Grammar School in 1762, and was the only son to produce male heirs. Among Robert’s uncles were a Major Edward Clayton in the army and Richard, a Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in Ireland. The family continued to concentrate on the law and the military in Robert’s generation. His older brother, another Richard, was a successful barrister and diplomat and was created a baronet in 1774. Richard, as head of the family, periodically petitioned army administrators for higher rank and leave for his brother Robert. -family information derived from Henry Hepburn, The Clayton Family (1904), R. Stewart-Brown, The Tower of Liverpool (1910), The Admission Register of the Manchester School (1866).

Our Robert purchased an ensigncy in the 17th regiment on Dec. 9, 1767, at the age of twenty-one. He received his Lieutenantcy in the regiment without purchase on July 19, 1771, following the death of Lieutenant William Byrd (or Bird), an American belonging to the well-known planter family of Virginia. Vacancies by death ordinarily could not be sold, and the promotion went to the senior ensign within the regiment. The next step in Robert’s career illustrates how officers attempted to use family connections to get ahead in the Georgian army. When a company became vacant for purchase in the 17th in 1774, brother Richard contacted General John Burgoyne (of future Saratoga fame and an acquaintance of Richard’s) and requested that he write to the secretary at war soliciting the promotion for Robert. Burgoyne wrote to Secretary Barrington describing Richard as “a gentleman of great fortune and worth, a steady supporter of Govt., & a friend to Lord Stanley and myself in Lancashire.” (Barrington Papers, J Burgoyne to Barrington, Dec. 26, 1774) This is classic patronage language of the time, offering political support in exchange for favors. In this case the letter was unsuccessful and the company went to an officer with considerably more service experience, but Robert was able to purchase the next vacant company (over the head of a senior lieutenant who lacked the money to purchase) six months later, on May 1, 1775, thus rising to command of a company after some seven and a half years of service. This was pretty fast promotion for peacetime service. In 1774, a look at the seven captains then serving with the 17th shows that five of them had reached the rank after thirteen or more years of service, one after ten years of service, and only one had been promoted about as rapidly as Clayton.

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Clayton served throughout the American Revolution with the regiment. In a memorial for promotion he submitted at the end of the war, he summarized, slightly out of order, his service: “went to America 1775 a Capt, was at Staten Is., Brooklyn, Brandy-Wine, White Plains, German-Town, White-Marsh, and storm of Stoney Pt where taken Pris. On being exchanged had leave to go to Europe, but declined and went with regt to Virg. and did duty till Yorktown, again Pris.” (WO1:1021, f. 193, memorial of Robert Clayton enclosed in Richard Clayton to Secretary at War, 19 Jan 1784). Clayton’s commitment to the struggle was discussed in a September, 1781 letter from brother Richard petitioning leave for Robert. He apologized for bothering them with a second request for leave, but the first had arrived as Robert’s regiment was embarked for Virginia, and Robert had refused it, writing back “ the duty he owed to the King was superior with him to every other consideration and…he would willingly run any loss or suffer any inconvenience, rather than leave the Regiment situated as it then was.” Richard stated that his brother had been in no less than twelve actions, and “that he was an Enthusiast of the American Service, in refusing to leave the Regt when they had any immediate objective in view…” (WO1:1010, f. 599, Richard Clayton to Jenkinson 30 Sept 1781).

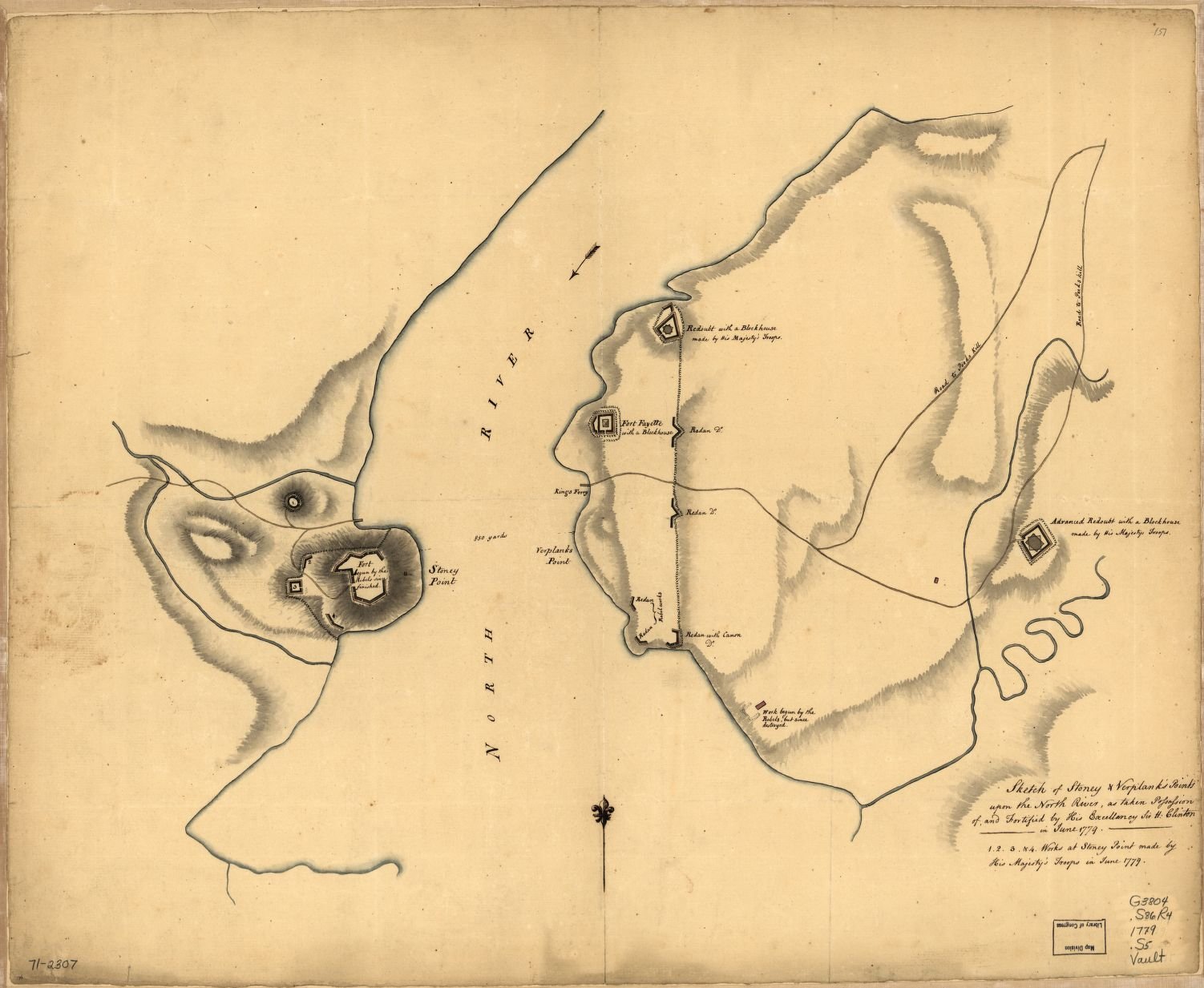

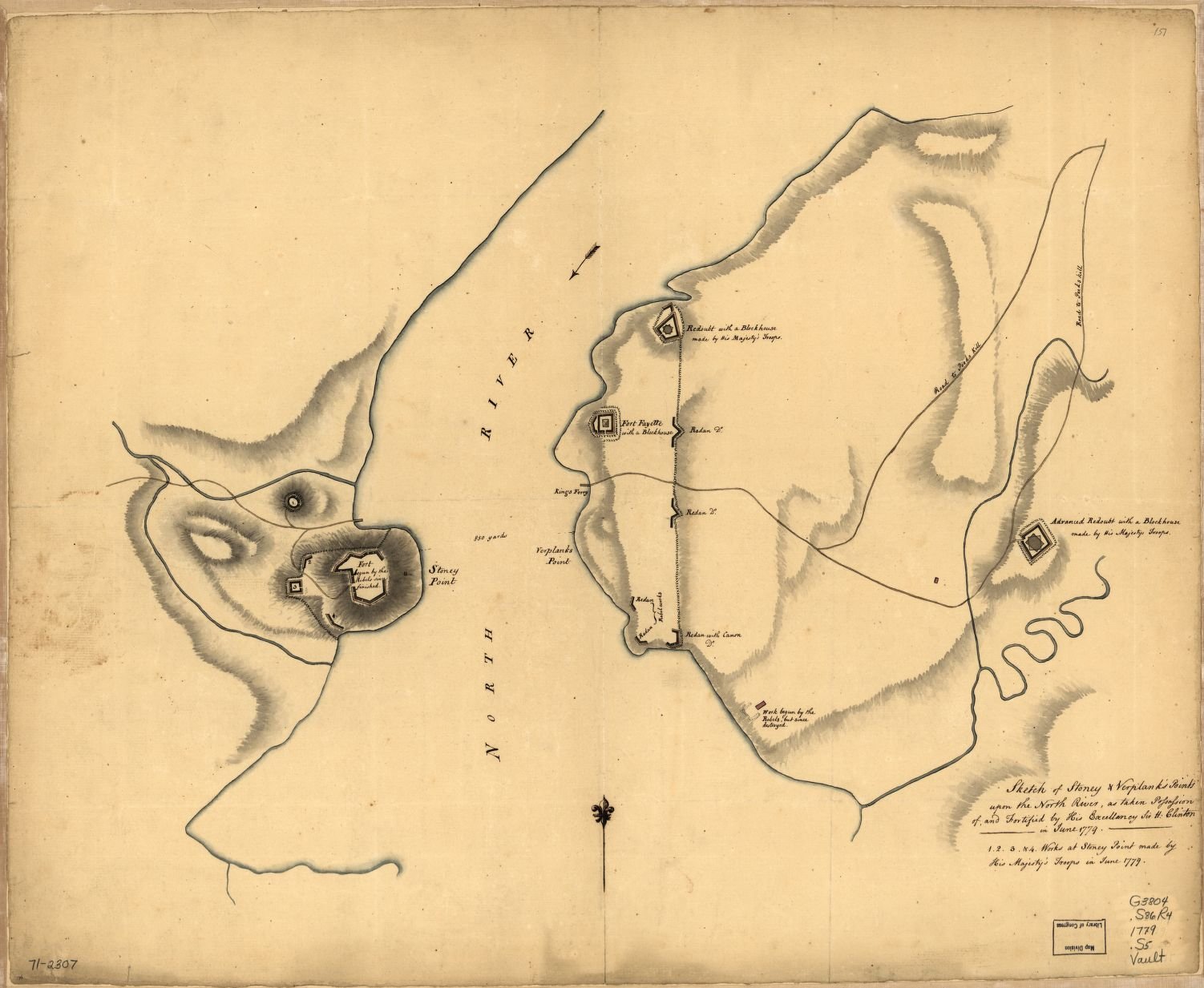

The only glimpse of Robert Clayton on active service that I have found comes from the court-martial of Henry Johnson following the loss of Stoney Point. Clayton was serving as commander of three companies of the 17th that formed part of the garrison of the upper works of the position. Soon after the action began Lieutenant John Roberts of the artillery encountered “Clayton and a party of men lining the parapet; that Captain Clayton seeing that he (the witness) belonged to the Artillery (tho he believes he did not know him to be an officer, from the manner in which he spoke to him) said ‘For Gods sake, why are not the Artillery here made use of, as the Enemy are in the hollow, and crossing the Water’”. Roberts answered that there was no ammunition for the guns, as it was not customarily stored with them, and these guns could not bear on the enemy in any case. Clayton clearly had a temper, and artillery lieutenants were not used to being yelled at by infantry captains. (WO71:93, Court Martial of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Johnson, Jan. 30, 1781, p. 55).

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of Mount Vernon

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of Mount Vernon

It is worth noting that at the time of his memorial in 1784 Robert Clayton was commanding the regiment, as he had at several points during the war when more senior officers were absent. Colonels did not generally serve with their regiments, and lieutenant colonels and majors were often absent commanding larger forces, on staff duties, or due to illness or leave, and it was quite common for regiments to be commanded by the senior captain present. The 1784 memorial was prompted by the attempt of William Scott, a more junior captain in the 17th, to purchase the majority of the regiment ahead of Robert Clayton. The following year Robert achieved his goal and purchased the majority of the 17th on July 27, 1785.

Robert retired in 1787 by exchanging with a half pay major of the 82nd Foot. This arrangement illustrates how officers overcame the absence of a formal retirement system by using what the army made available to them. The half pay system provided a stipend to officers who had been retired by the army when the forces were downsized at the end of a major conflict. A high numbered regiment like the 82nd was disbanded at the end of the Revolution and its officers were placed on half pay. If they wanted to get back onto active service, they would exchange with officers like Clayton who wanted to retire with some form of pension. According to a memorial Clayton submitted to the War Office when he was 80, they used an arrangement called “paying the difference.” The value of seven years of half-pay was subtracted from what Clayton had paid for the majority in 1785, and the officer of the 82nd paid the difference in cash to Clayton. This was probably a relatively small sum for the half-pay officer, and if Clayton lived for more than seven years on the half-pay (as he did, receiving half-pay for more than fifty years), the rest was gravy. (WO25:752 f, 121)

In 1786, near the end of his military career, he married Christophera Baldwin, daughter of a clergyman. They lived at the Larches, Wigan during the remainder of his long life. In 1828 the wheel of inheritance took another turn with the death of his brother, Sir Richard Clayton, Bt, who had already inherited the family estate on the death of their remaining uncles back in the 1770s. Robert inherited the family manors and his brother’s title of baronet, and was thus Sir Robert Clayton, bart. on his death in 1839. He died childless, and left his estate to his wife and to a niece, the daughter of his brother Richard. (PCC Will of Sir Robert Clayton Bart. Proved 1839)

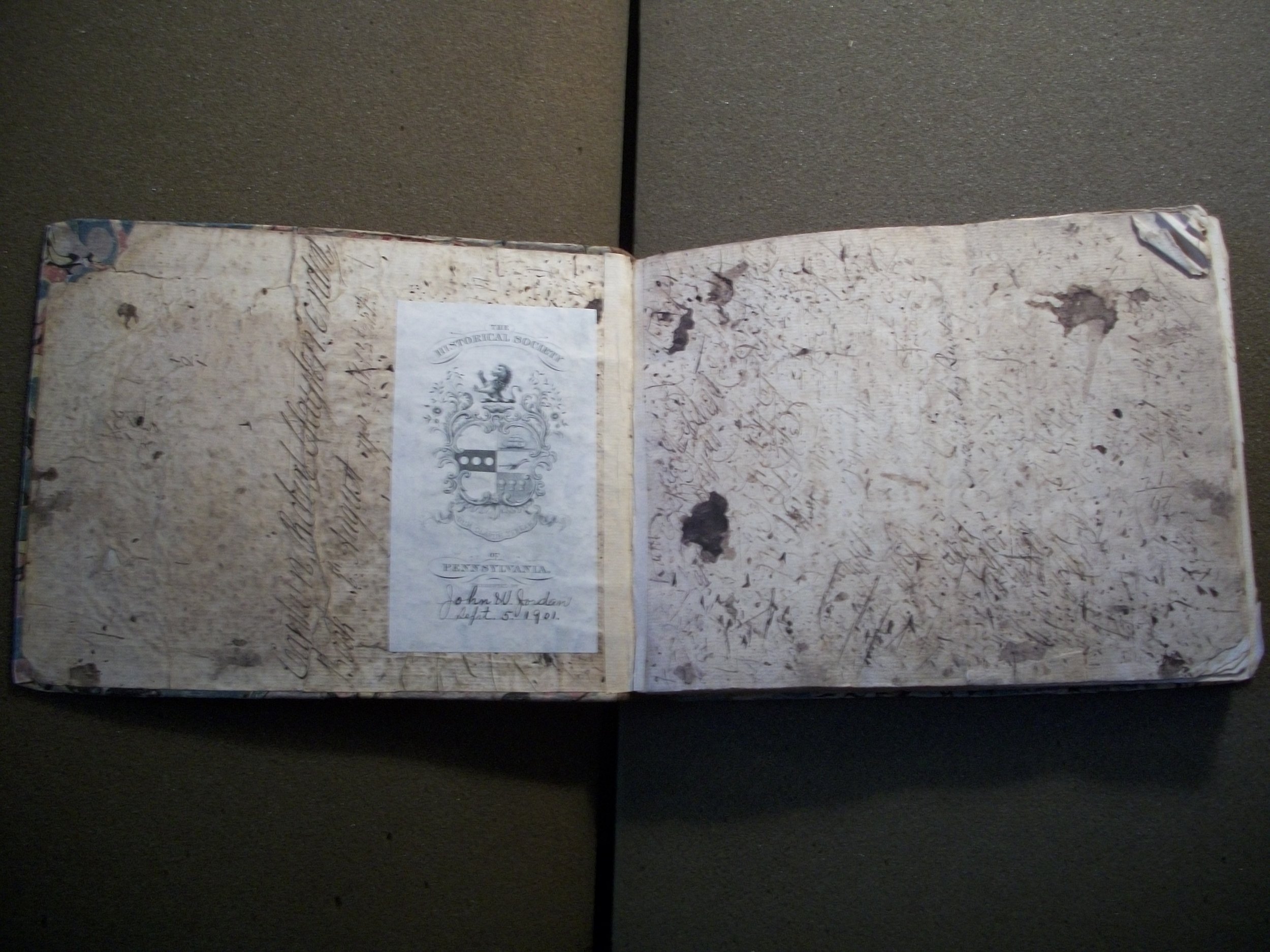

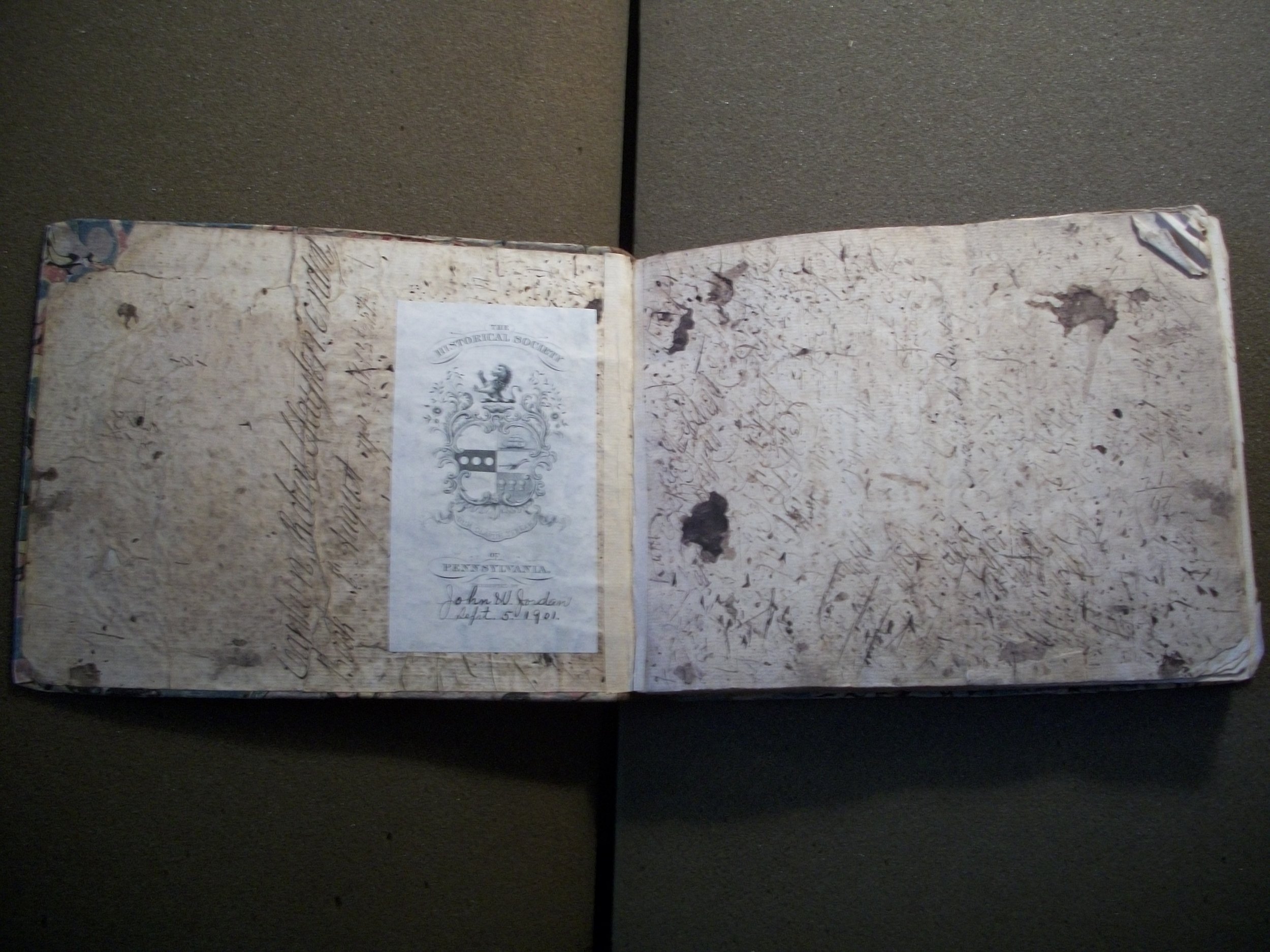

Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

An orderly book kept by Clayton in 1778-79 can be viewed on microfilm at the David Library, and excerpts have been published in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, v. 25,(1901).

Dr. Mark Odintz

Dr. Mark Odintz

conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

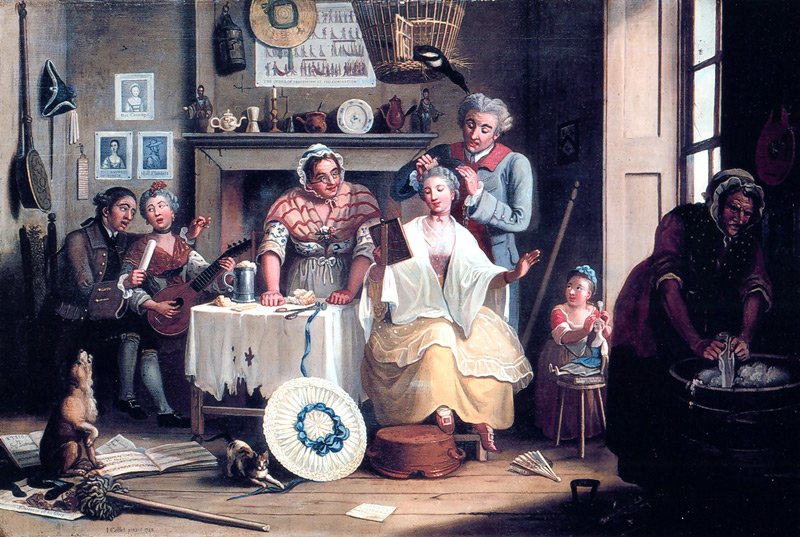

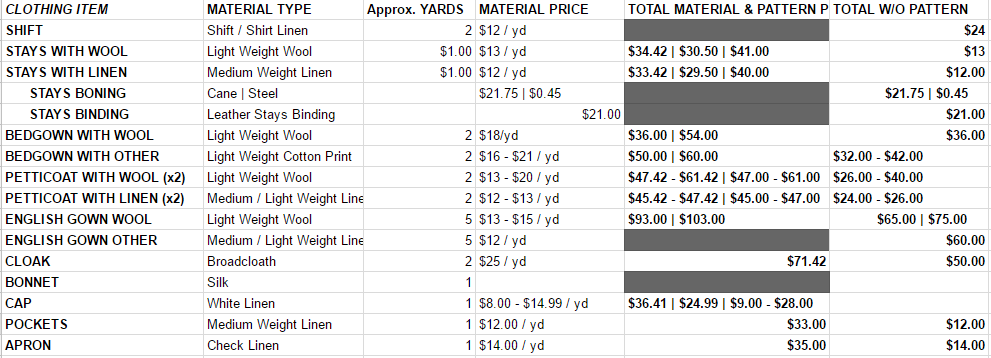

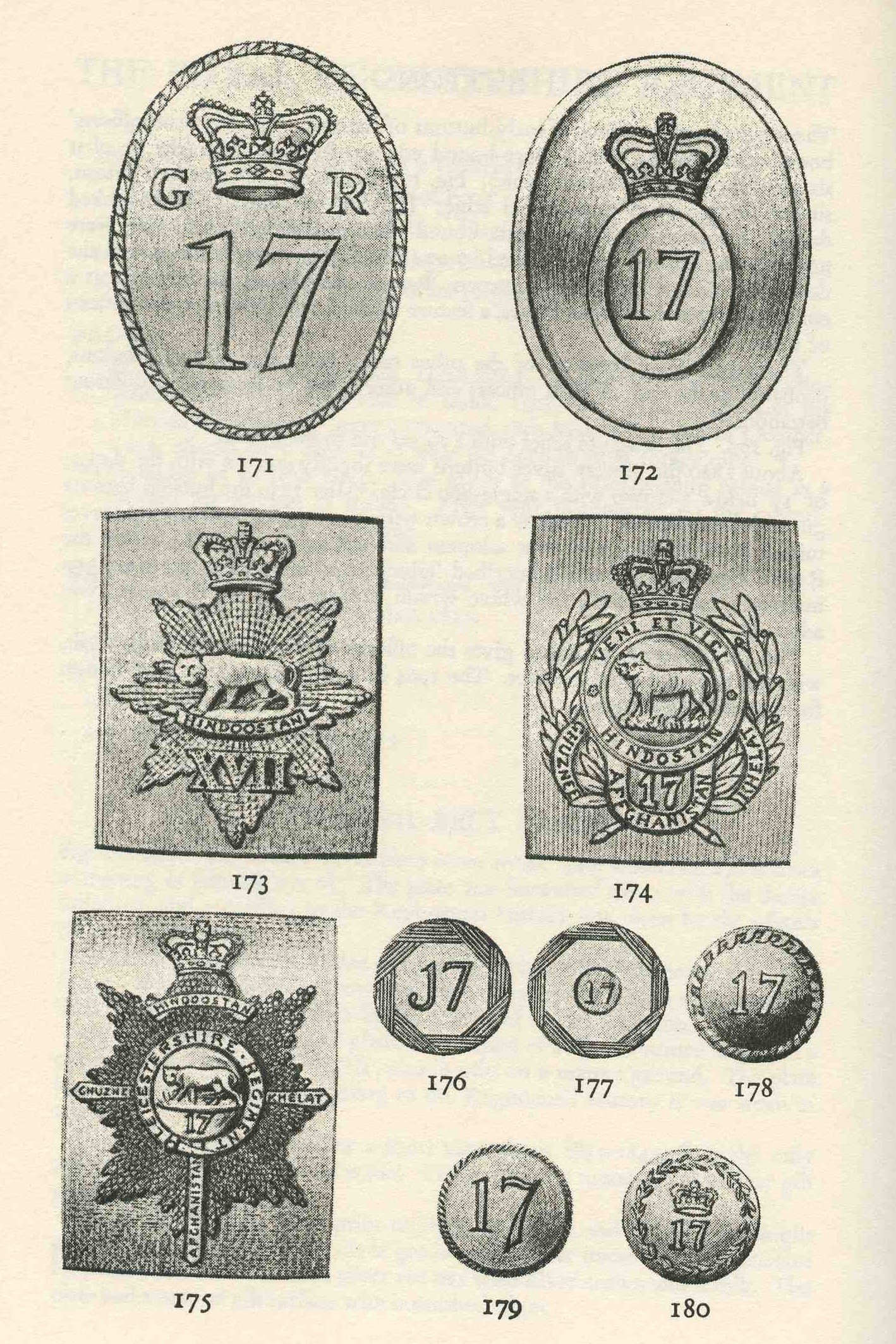

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

JENNA SCHNITZERis a a member of the 62d Regiment of Foot. She has been a Historic Interpreter since 1993. When she isn't researching or doing experimental archaeology she is either antiquing or restoring the 18th century home she owns with her Husband Eric and their two very bossy cats Georgie and Charlotte.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

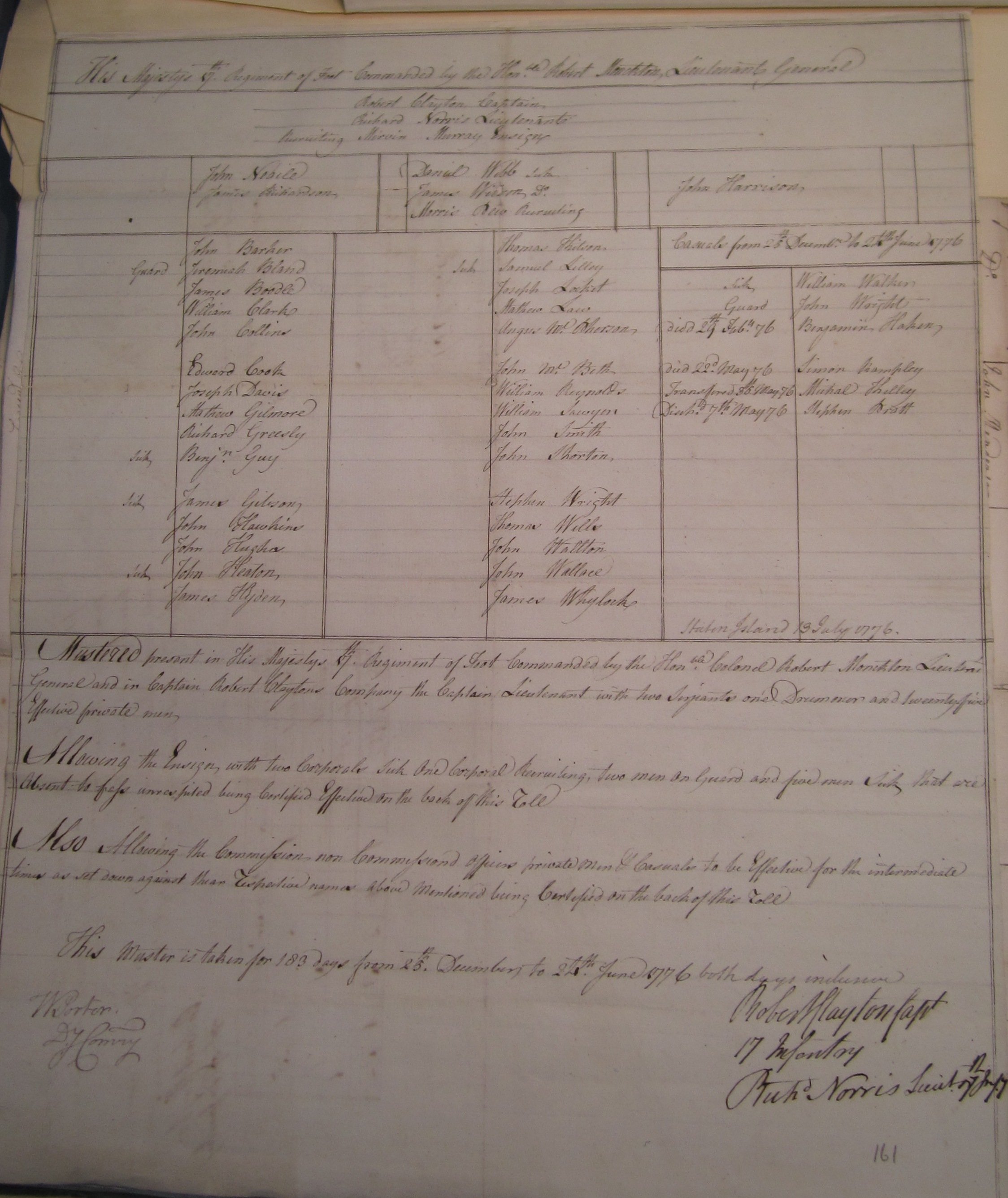

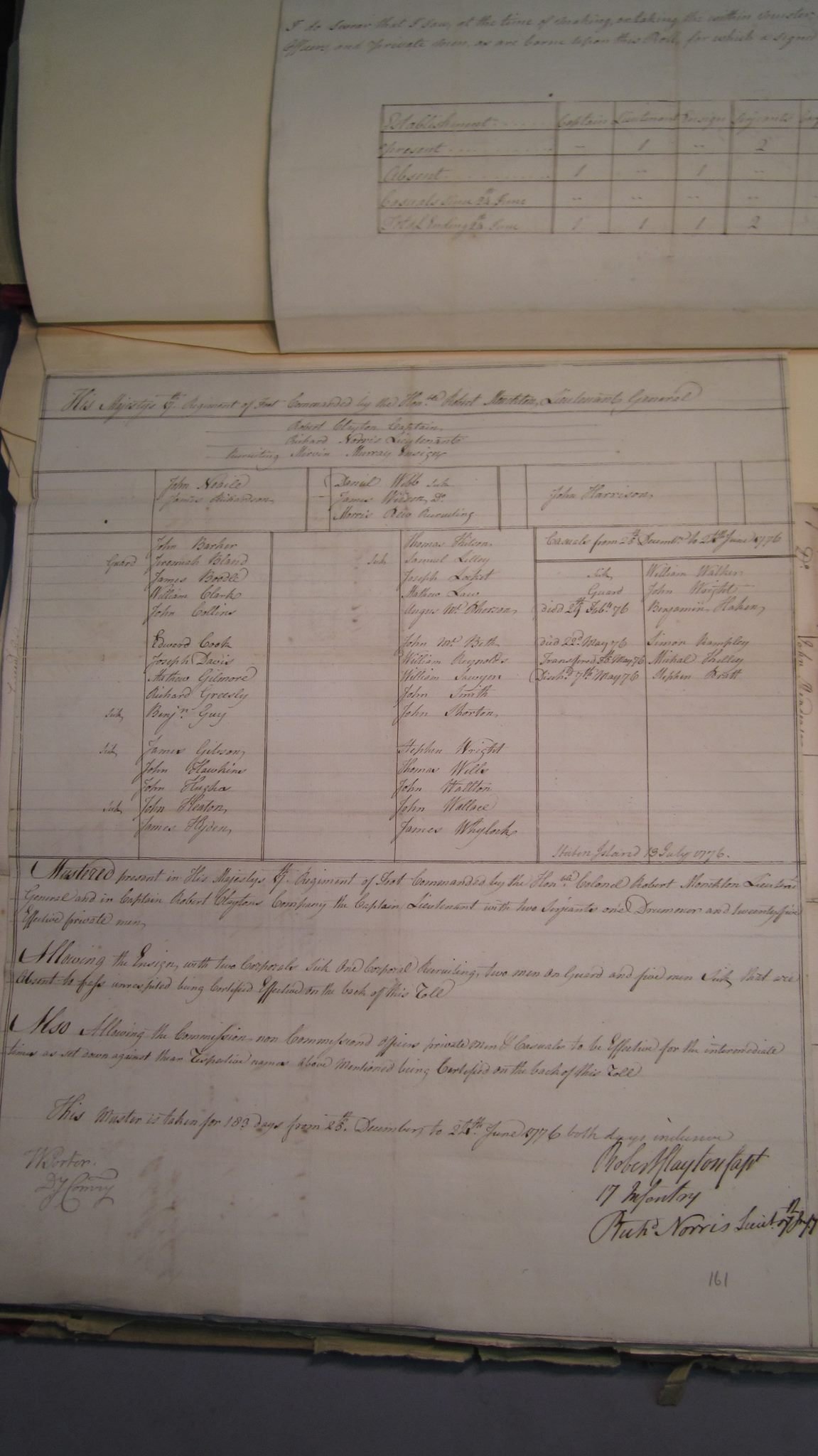

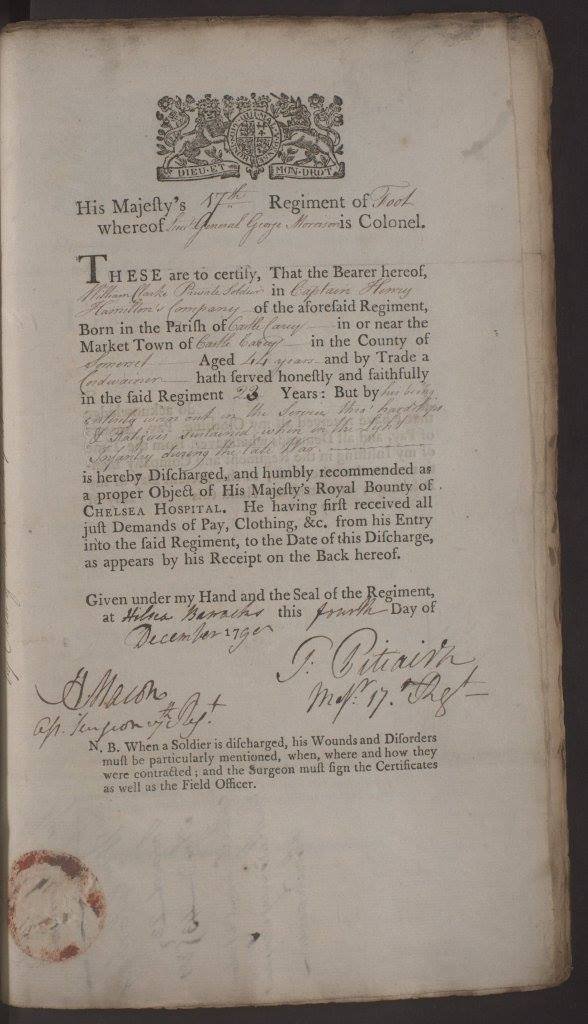

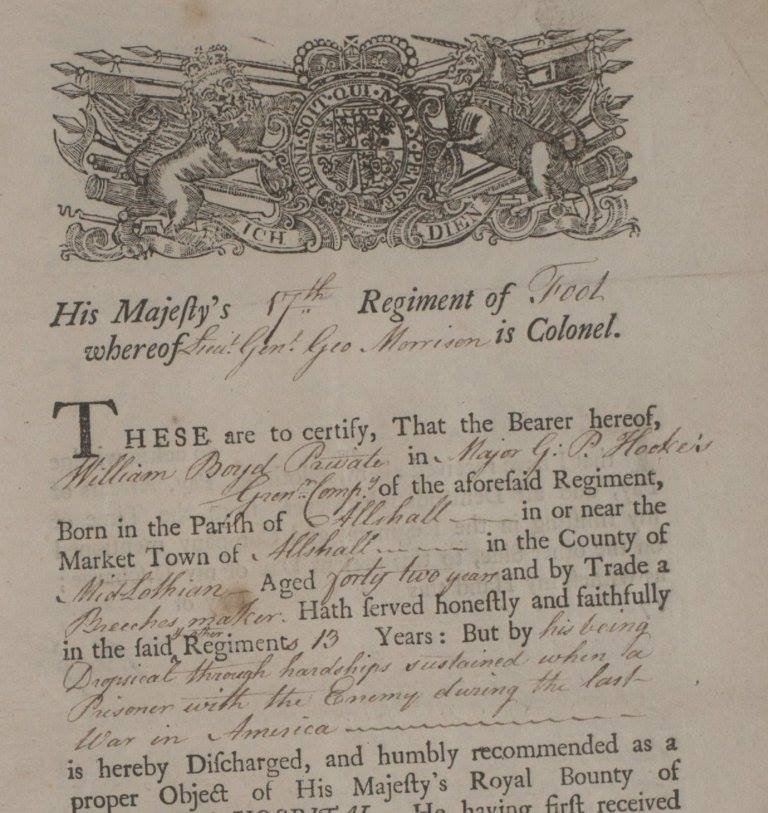

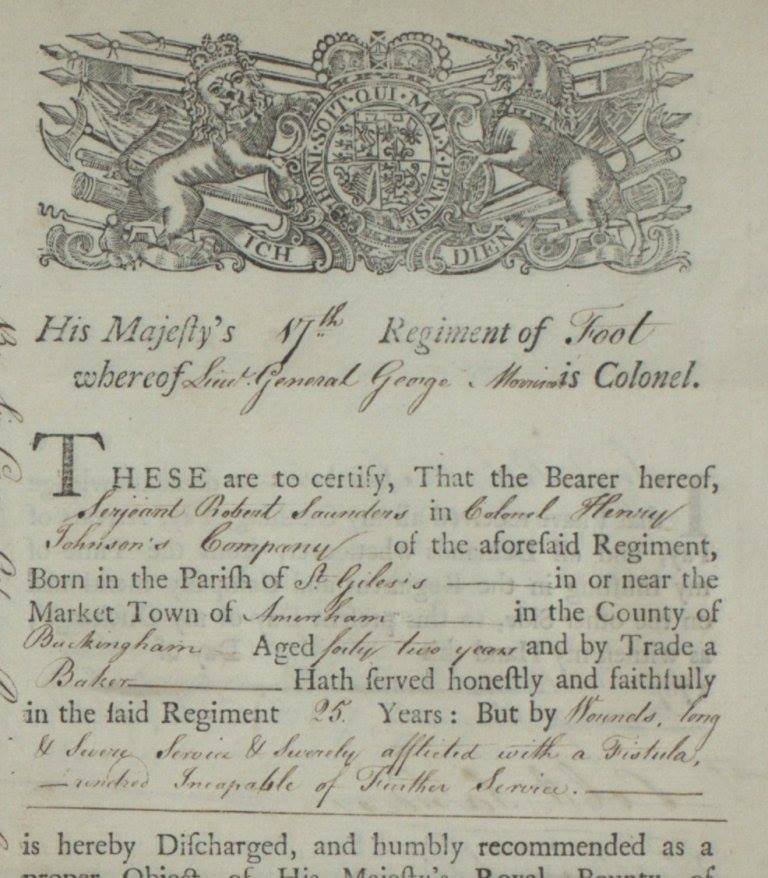

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books. Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

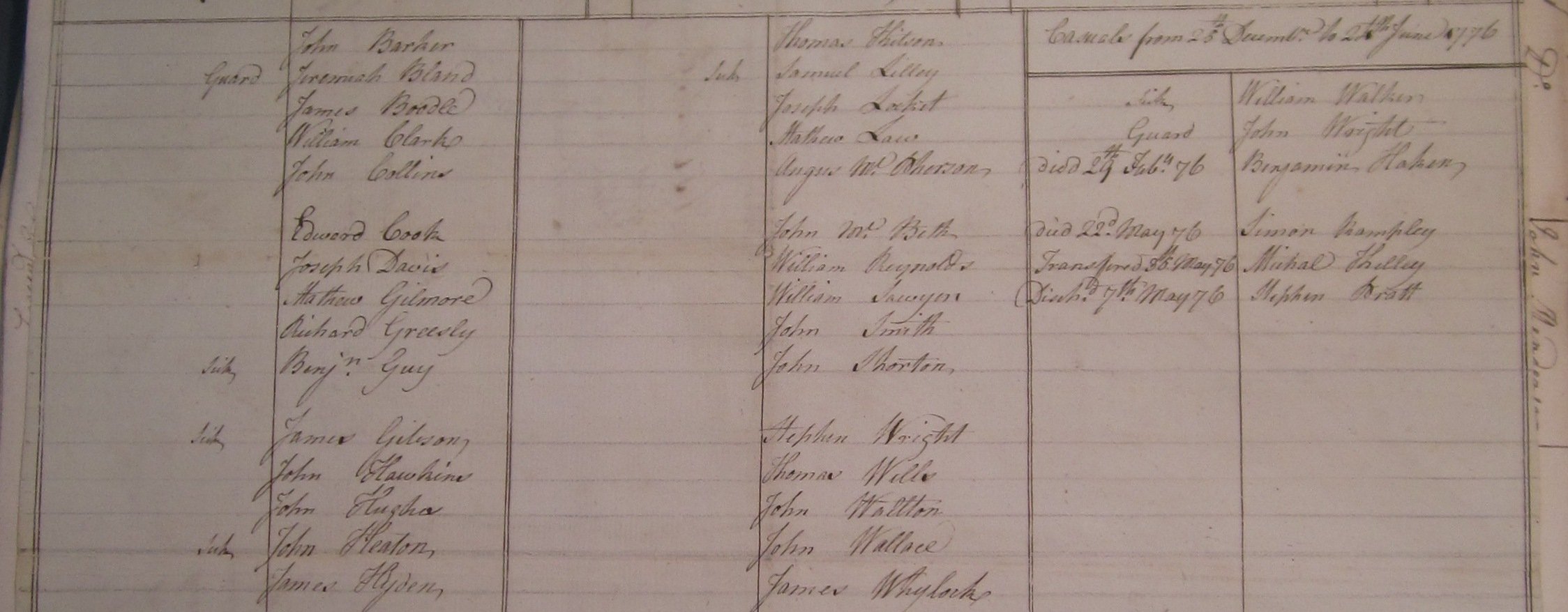

Most folks raised in the western tradition will want to read these from the top-down rather than the bottom-up, despite the fact that your most important information for understanding when and where is down near the bottom. So we’re going to look at the bottom first, for the most important material. Then we’ll move back to the top. And then deal with the center portion, where everyone inevitably ends up.

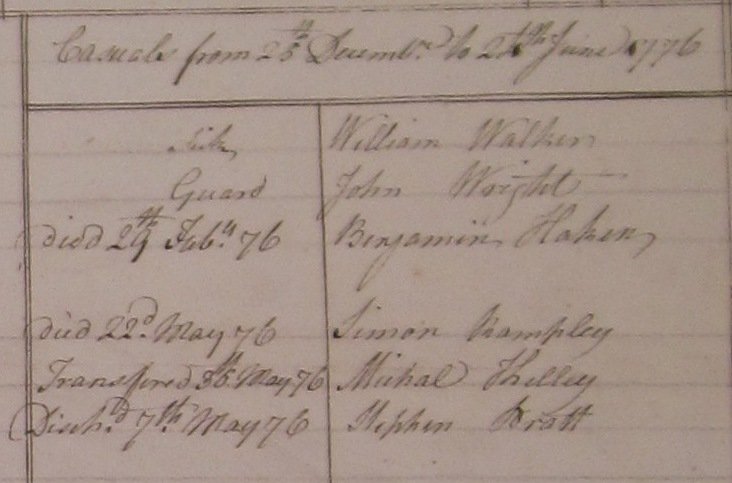

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

Here’s another transcript for you: “Sick William WalkerGuard John WrightDied 29th Feby 76 Benjamin HakenDied 22d May 76 Simon RampleyTransfered 35th May 76 Michal KelleyDischd 7th May 76 Stephen Bratt”

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

WILL TATUMreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

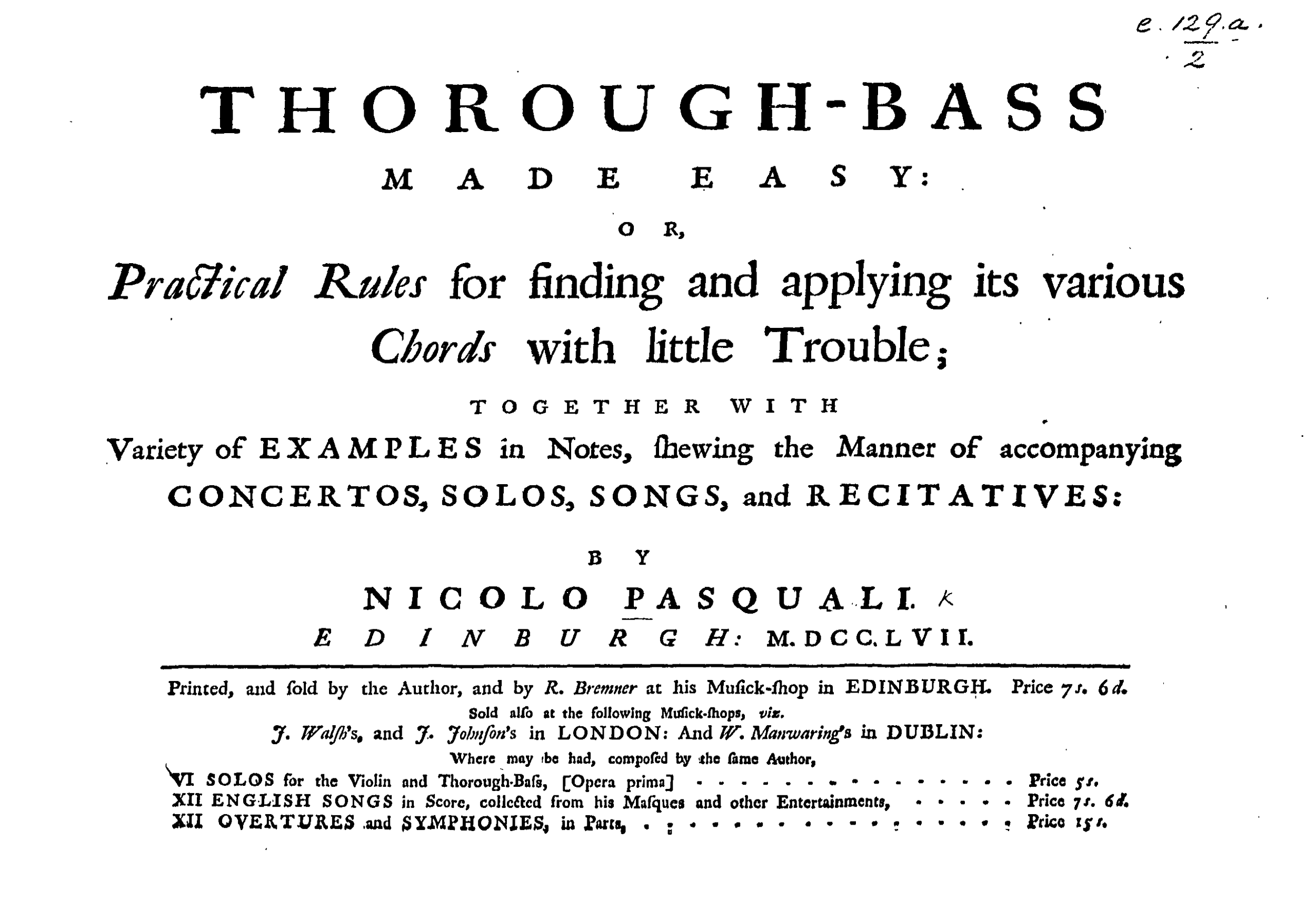

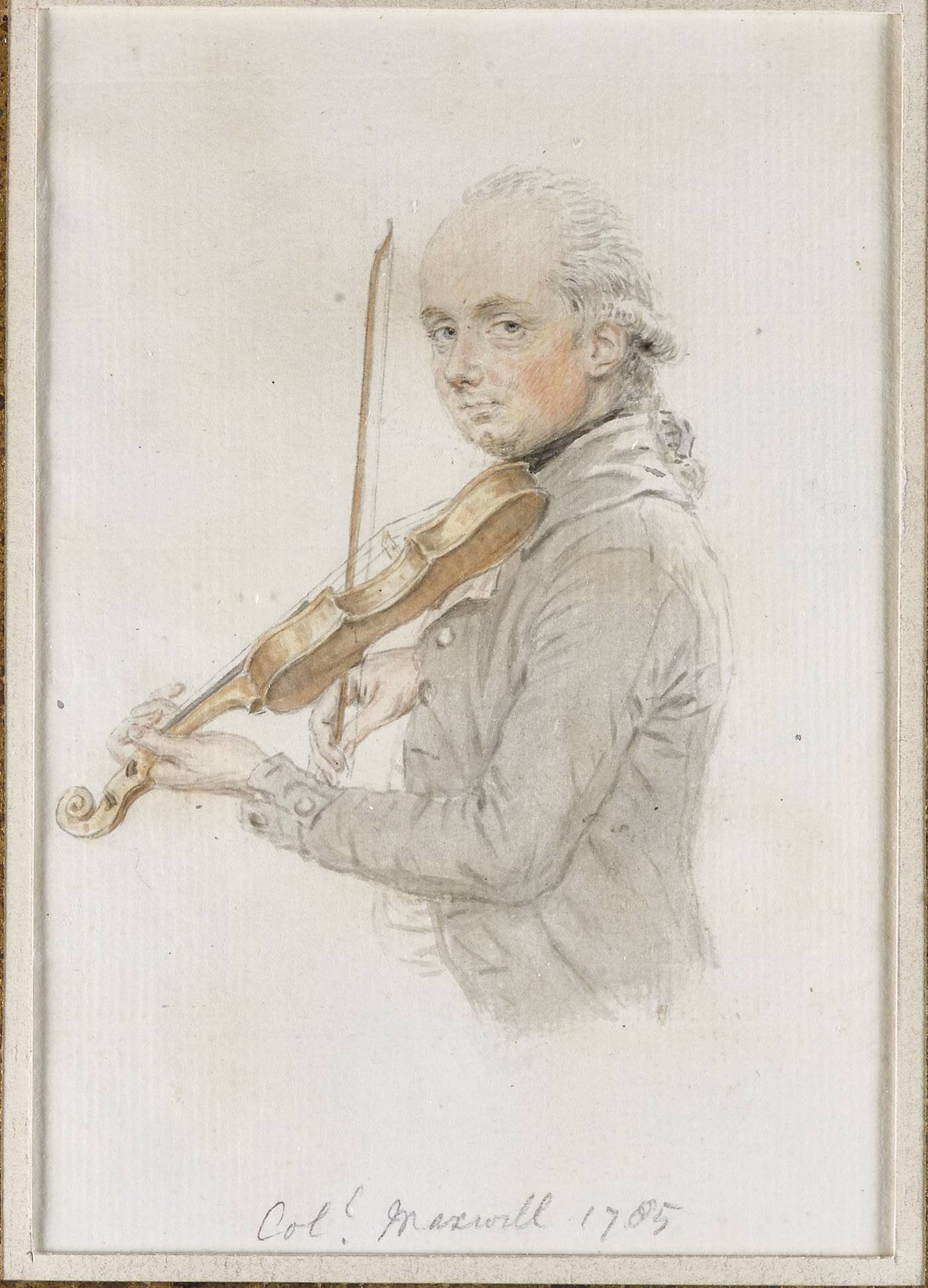

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

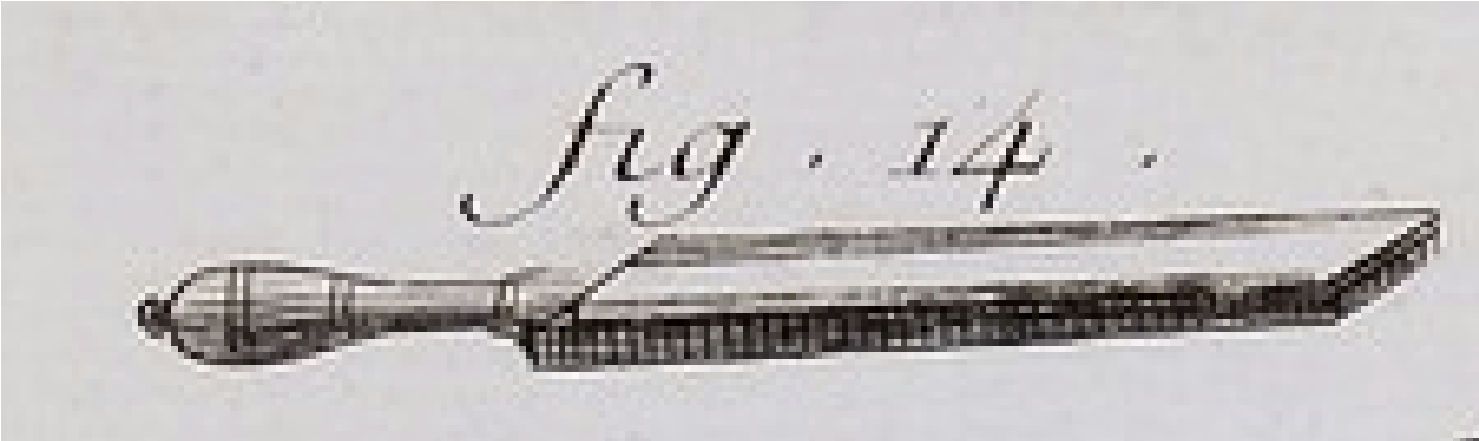

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations: violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo

Mary Sherlockis a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head follower' for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009.

Mary Sherlockis a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head follower' for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009. That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory. Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Unknown officer of the 17th Regiment, possibly William Leslie, mourning miniature

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of

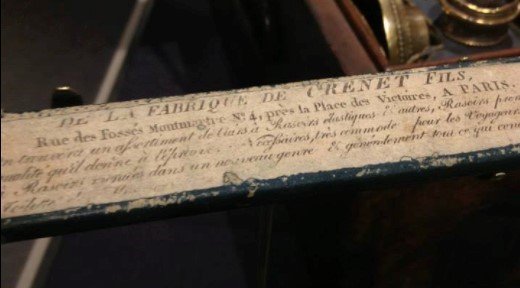

Map of Stony Point, courtesy of  Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Opening page of Captain Clayton's Orderly Book, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Dr. Mark Odintz

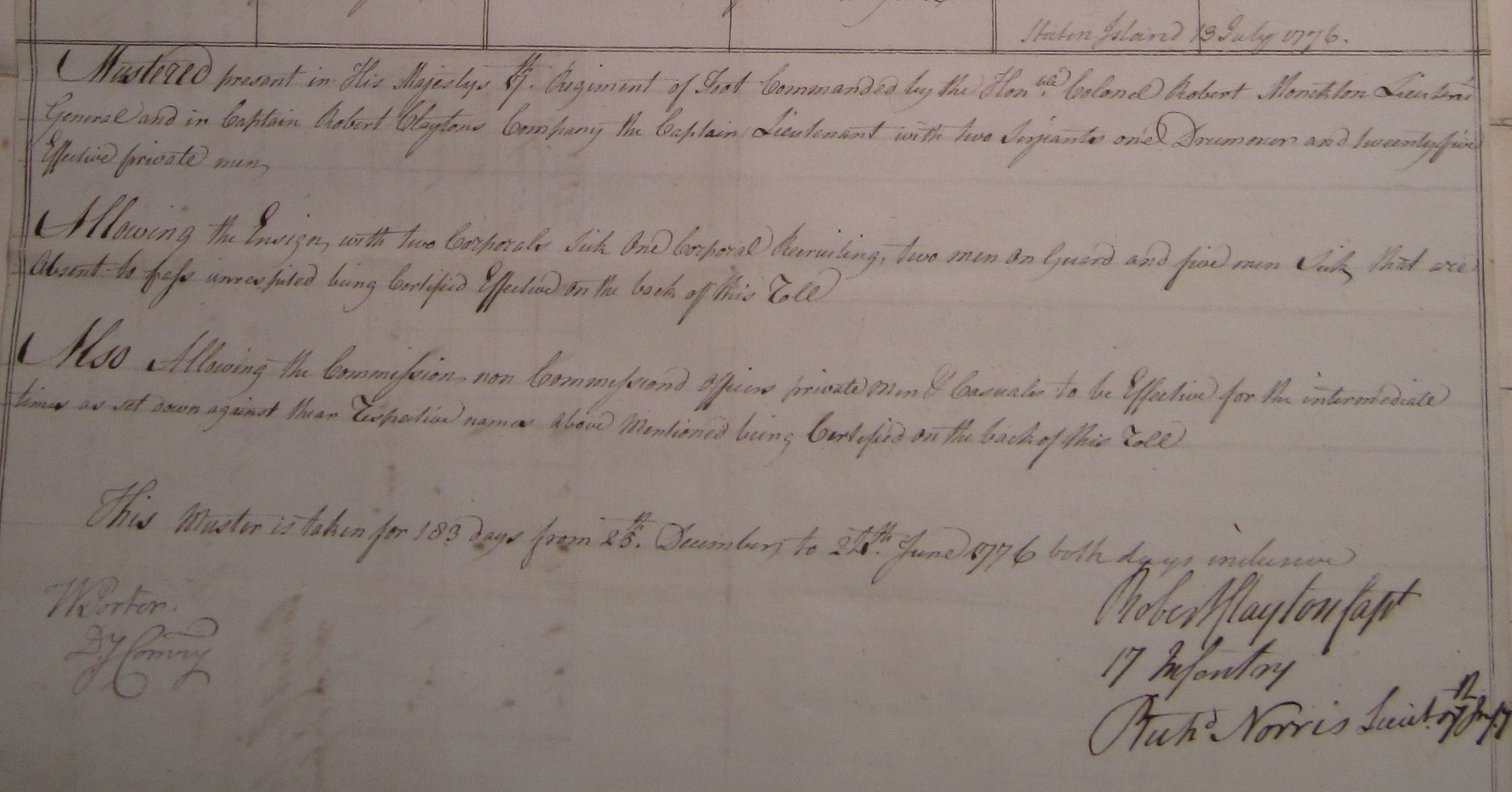

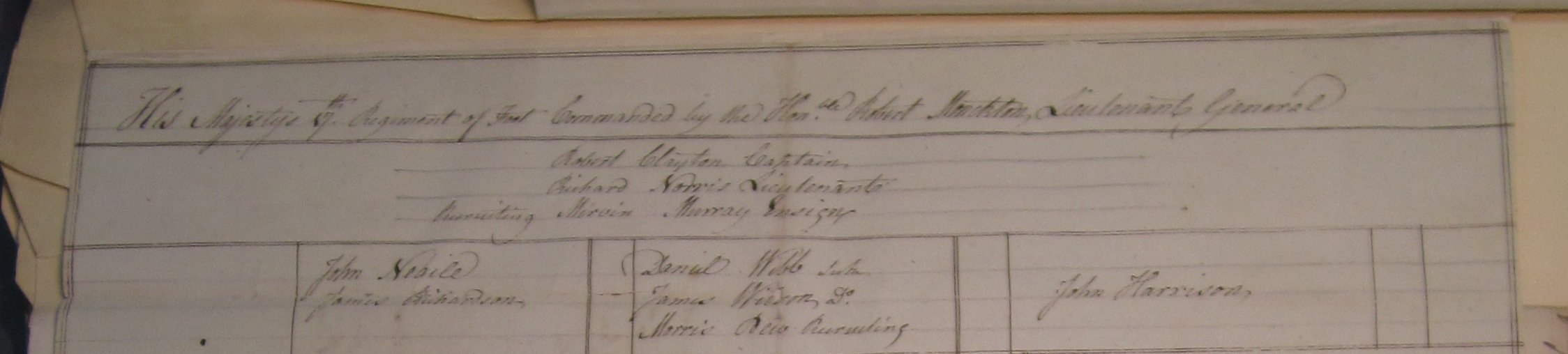

Dr. Mark Odintz Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

Muster roll for Captain Robert Clayton’s Company, HM 17th Regiment of Infantry, December 25, 1775-June 24, 1776; WO 12/3406/2; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

Photo by

Photo by